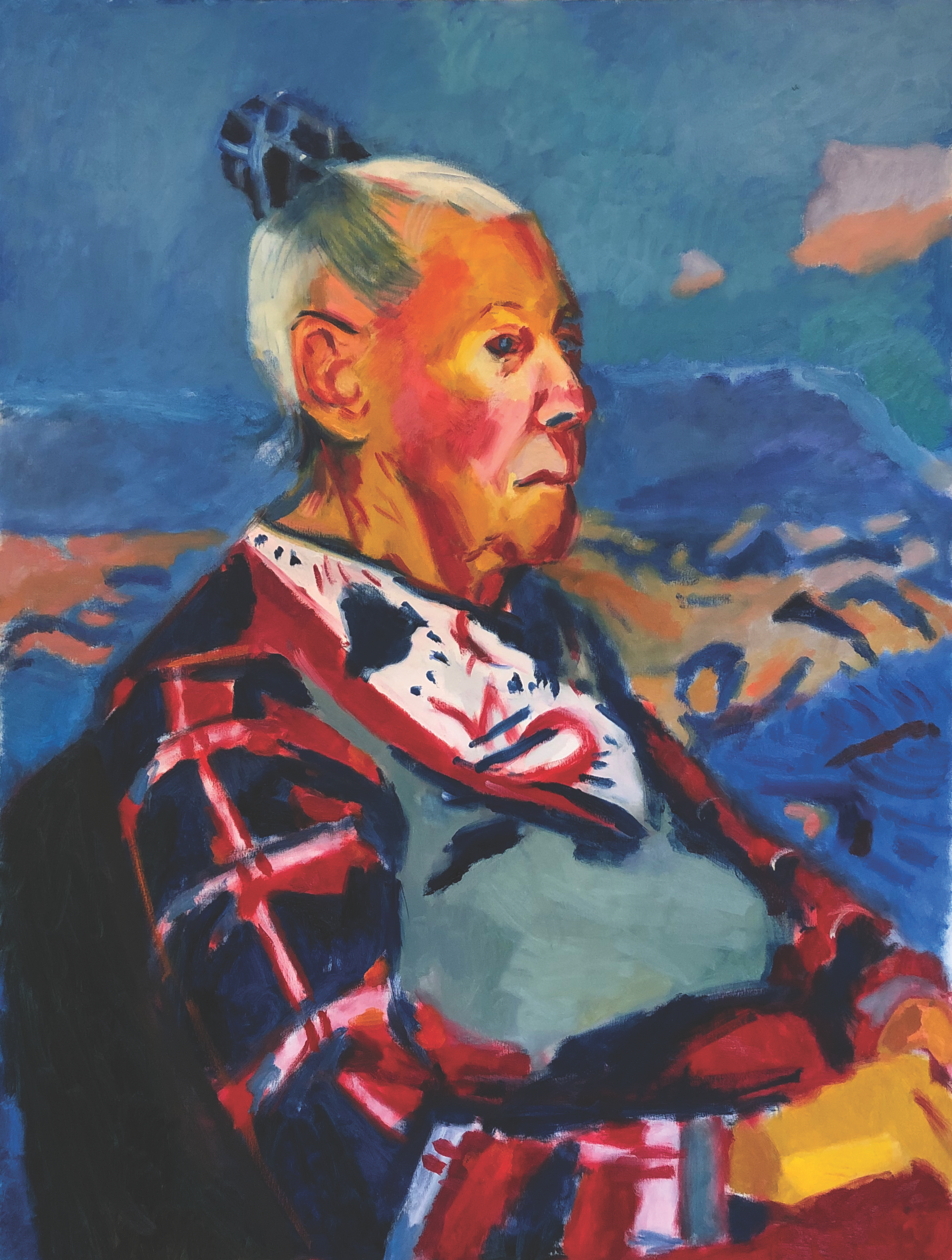

ART: NATALIA ZOURABOVA

The Treasure My Mother Couldn’t Bestow

“TOO MUCH!” said my mother. “I’ll give you fifteen.”

“It’s okay, ma!” I whined, blushing.

Ignoring me, she counted out some crumpled bills.

The vendor looked at the cash and raised his eyebrows, as if to say, “That’s it??” She shrugged and restored the money to her wallet and the wallet to her pocketbook, and it was only then that he made a beckoning motion with his fingertips.

“You drive a hard bargain, lady,” he said, handing her the delicate necklace in its box.

“Set a nicer price, and bargaining won’t be so hard.”

“Sure. I’ll just go broke,” he agreed, his manner now affable, almost affectionate.

As we walked away my mother handed me the necklace, saying “Wear it in good health,” and rushed over to look at another vendor’s stall. She enjoyed shopping. I did not. She had certain street smarts, a certain piquant taste for life, a certain knowledge of stitching and fabrics and materials in general, including the

materials that compose other people, that I assumed would be mine over time.

But I graduated from college, from graduate school, I even graduated from teaching in graduate school, having retired (early, but still!)—and yet that worldly maturity eluded me.

I think of it as seychel, a kind of seasoned wisdom, and now that my mother is no longer alive I have despaired of acquiring it. It seems to me, too, that without it, I lack the quality that allows you to be very fully alive in your body, in your senses, unsentimental, morally alert, registering the blows and injustices

but also the acute pleasures, a mensch, really. Instead I march along wearing 20-year-old faded broken eyeglasses filigreed with Krazyglue, and sneakers with a toe that pokes out, scarcely knowing the value of a dollar, and with the feeling that my life is printed on acetate, everything inscribed on it becoming a blur because I lack the correct fixative, the lucid if faintly vinegary seychel that allows things to register and be of consequence.

I once said to my mother, “I don’t think I’ll get breast cancer. After all, you didn’t.”

She regarded me with surprise. “But we’ve had different lives,” she said, stating something obvious that still surprises me. She’d had four children; I’d had none. She’d grown up poor in the Bronx. She’d won the prize for mercantile mathematics at Walton High School when she graduated at the age of fifteen. Her first language was Yiddish. Hitler came to power when she was thirteen. She attended the opera for decades before there were supertitles or subtitles, studying the story and letting the music carry her. She was such a fast typist that the office manager suggested she was stealing typewriter ribbons. Recounting this my mother made a face as if to say, The idiocy of that woman!

My mother couldn’t help adding: “Slow up the work, so that the office supplies last!”

I picked up her hand and kissed it.

She made no acknowledgment of my doing this, since she was also the queen of a certain kind of comic timing. Her hand remained inert. But then she winked at me. I guffawed.

It seemed to me that all her life wisdom was contained in that glinting wink.

MANY HAVE NOTED that American Jewish women traditionally had a different feminine ideal from WASP women because they were valued if they went out into the marketplace so that their husbands could study and pray. The ideal Jewish woman was not spared contact with the world. She fended for the family.

And in the United States there were many pioneering Jewish businesswomen who succeeded despite the vast obstacles sexist culture imposed: Lillian Vernon, Georgette Klinger, Lillian Cahn (co-founder of Coach), Josephine Esther Mentzer (a.k.a. Estee Lauder), Jean Nidetch (Weight Watchers), and Ruth

Handler (co-founder of Mattel), to name a few. They were all either immigrants—having escaped Hitler’s Eastern Europe—or the first-generation daughters of immigrants. Most had survived loss and change, and perhaps for this reason knew to take responsibility for their futures, comprehending that this is it.

The woman born Lilli Menasche named her company after the suburb she moved up to when she married—Mount Vernon—and then, after her second divorce, renamed herself for her company. When I was growing up, my older sister anticipated the arrival of the Lillian Vernon catalog, with its caravanserai of affordable novelties—the clothes hangers painted like leaping Russian dancers, the Chinese children clasping hands around a shimmering pin cushion, the tomato press from Italy. My sister ironed each page flat with her palm. Pieces of the world were on offer, tastes of the many places she one day meant

to see—although as it happened she got to experience just a few directly, succumbing to multiple sclerosis in her late twenties. It made the catalog, in memory, even more important to me.

So I was excited to meet Lillian Vernon herself when she donated an elegant townhouse to NYU to be their creative writing center. She had a golden gut, she told me. “In my business,” she once said, “it’s like being a social scientist, understanding what people like to buy.” I explained to her what her catalog meant to my sister and me when we were growing up in the Bronx. She fixed me with a sharp gaze. “Didja get out?” she barked. I was flummoxed. “I live in Brooklyn now,” I faltered.

Only later did it occur to me that the Bronx she pictured was not my verdant Riverdale but the choking, grim borough my mother herself grew up in. After all, she was almost my mother’s age. And her question about getting out also rang differently, knowing that her family fled Leipzig, Germany, when she was a girl in 1933.

SEYCHEL, with its rasping guttural center, like something scraping the earth, derives from the Hebrew word to be bright and to see clearly, and is thus associated with Haskalah, enlightenment, but has a demotic, Yiddish spin. My mother always knew the name of a doctor’s receptionist, and how many children she had, and would ask about them. She did this, I presumed, because it might increase the chances of being fit into the doctor’s schedule, and also because she was a mother herself, and truly interested. Maybe because I wasn’t a mother I lacked this sense— although later it occurred to me that there are many silly and even histrionic mothers. No, the seychel came from someplace else. It came from her going to a secretarial job in Manhattan at the age of fifteen, using forged working papers. It came from a certain kind of suffering that she’d allowed herself to feel, and a certain affinity with other people that came from that.

“I’m Russian, too,” she told the bathroom attendant at Tatiana’s in Brighton Beach: She always tipped a bathroom attendant. In a Saul Bellow short story, “The Old System,” he describes an old Jewish family matriarch: “She had a straight sharp nose. To cut mercy like a cotton thread.”

My mother’s seychel allowed for mercy and the happiness of life, but she could look out for her own interests if need be. “I didn’t let anybody stand in my way,” said Lillian Vernon. I’m sure.

So, is it too late for me? Born of a middle-class family, a daydreamer, having spent my life in libraries and classrooms, something in me spares myself in a way that my mother didn’t spare herself. I am frightened; I draw back. I don’t want to be burnt by the sparking, roaring blade. I observe. I don’t know how to add things up properly. I lack the purposefulness that some girlfriends of mine have, swaggering out, buffaloing their way, surmising, working the angles, kind but never patsies, making things happen. My head is stuffed with pages, and only pages. The first successful Coach bag was modeled on a type of paper shopping bag Mrs. Cahn used as a girl to deliver homemade noodles to customers in Wilkes-Barre. She, like my mother, understood other women to be like her. I feel myself to be eccentric, as I likely am. Who else would wear these patched, cockeyed glasses and busted sneakers—thinking, nobody will judge me on how I look, people aren’t as superficial as that?

And yet, although I don’t have seychel, I still have the memory and protection of my mother’s. With her sardonic canniness that is also a joyful acceptance of the way that people really are. She taps me on the shoulder from time to time and whispers, “Put on a new shirt.”

Bonnie Friedman is the author of Writing Past Dark (Harper-Collins) and the novel Chartreuse, forthcoming with Europa.