Is Writing Spiritual? Two Books Say Yes.

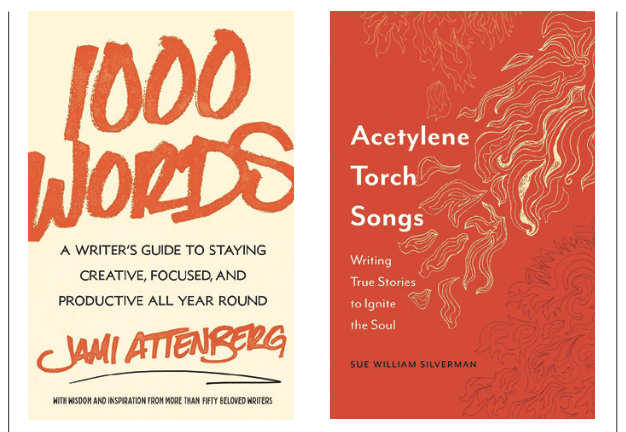

“Writing is holy,” author Patricia Lockwood once said, and there couldn’t be a more appropriate assertion with which to begin an article about two new books that take different, but equally spiritual approaches, to the craft: 1000 Words: A Writer’s Guide to Staying Creative, Focused, and Productive All Year Round by Jami Attenberg (Simon and Schuster, $24.99), and Acetylene Torch Songs: Writing True Stories to Ignite the Soul, by Sue William Silverman (University of Nebraska Press, $23.95).

In the summer of 2018, Attenberg, author of the memoir I Came All This Way to Meet You, as well as a number of novels including the beloved The Middlesteins, All Grown Up, and Saint Mazie, began a writing sprint with a friend: 1000 words a day for fourteen days, “to shut out the noise” and “push to the other side” of their projects. What started as a pact became a movement via the hashtag

#1000wordsofsummer, to which writers flocked to find a community of others ready to crank out sentences every day. 1000 Words is a collection of Attenberg’s thoughts about writing, not writing, and how to keep writing, as well as previously published letters from authors, such as Meg Wolitzer, Roxane Gay, Alexander Chee, and Celeste Ng, who all contributed to Craft Talk, Attenberg’s newsletter, during 1000 Words of Summer.

Attenberg knows all the reasons people avoid writing, and she’s not afraid to confront us about them. She understands how innately tender and vulnerable the writing process is (“On a bad writing day, it’s easy to forget the enjoyment of making sentences—how pleasing it can be when it’s going well.”). She knows how damaging those “30 Under 30” lists can be, so she brings us Mira Jacob to remind us that there is no expiration date for creativity: “There is no list that will make you feel better than showing up for yourself and your pages, and everytime you do it, you get closer to the readers who are looking for you.”

1000 Words is a writing guide of a different stripe. In it you’ll find classic and golden advice like “Done is better than perfect,” and how vital it is to figure out how to incorporate our writing into the lives that we live, which unfortunately necessitate that we navigate lots and lots of distractions. What makes the book exceptional is the care Attenberg takes in her encouraging words. The process, whether journaling or novel-writing, doesn’t have to be about publication. It is about honoring our curiosity, and the desire within us to create.

“An ‘acetylene torch song,’ by my definition, is a written soulful obsession,” writes Sue William Silverman, a teacher of creative nonfiction whose latest essay collection is How to Survive Death and Other Inconveniences.

Our obsessions haunt us, and writing helps us to contend with what Silverman calls our “shadowy ghosts,” the darker aspects of ourselves. Throughout her book on the art and craft of nonfiction, practical advice (like writing prompts, vocabulary lessons, and even a section on how to assemble an essay collection, complete with graphics) are accompanied by examples of Silverman’s own work, including “Graduate Studies in Hebrew,” in which the narrator, a recent college graduate, struggles to maintain a cool, bold, American persona during a trip to Jerusalem. These lessons and examples show how we can take what keeps us up at night and shape it into something that not only longer controls us, but can potentially help others to heal.

Silverman is concerned with the role of memory in writing, specifically what happens when we don’t remember. “Lacunae” are missing spaces in memory, and Silverman urges writers to trust themselves when it comes to filling them. You can’t predict what will happen when you engage with those gaps, she says, but you can rely on your artistic ability, as well as craft techniques, to bring life to words on the page, to create a “mosaic” of memory via conjecture and rumination, instead of abandoning a moment or an idea because we can’t recall every single detail. “Readers trust us more—not less—when we imagine, reflect, speculate,” Silverman writes. “Your memories can’t be proved false because they are yours.”

In an essay called “Respect: Confessional Writing as Resistance,” Silverman brings to light why writing is such a profound and essential act at this particular moment in time. The #MeToo movement has encouraged women and other victims of abuse to exhume their deeply painful truths, in an atmosphere rife with fear and stigma, where “truth” is always questioned and evaluated, the victim is often accused of lying, and the powerful are protected from the consequences of their actions. It’s the well-founded fear of not being believed that drives us to keep our stories inside, but, as Silverman points out, “By confessing our stories, we confess yours too. That’s why the patriarchy is scared. We’re telling secrets.”

I began this examination of Attenberg and Silverman’s books with the assertion that writing is holy. Both of these creative guides–which are useful for anyone who wants to write, from the amateur to the pro–elevate not only the act of writing itself, but the writer too, encouraging them to nudge past fear, anxiety, and the mundane into a space where they can listen to their own voice, and hear its power.

Chanel Dubofsky is a writer living in Brooklyn, NY.