This Jewish Video Game is a Masterpiece

It’s not enough praise for me to say that Meredith Gran’s Perfect Tides (2022) is, by a nautical mile, the most compelling Jewish video game ever created. So let me put it this way: Perfect Tides is quite possibly the sharp- est, most brilliantly executed coming-of- age story about a young Jewish person created in any medium in the 21st century. On the heels of the “video game novel” Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow (which also had Jewish content, and a famous chapter that turned purgatory into a narrated video game), we may be seeing a breakthrough in the form.

If you’re the kind of person who played a few computer games when you were a kid and haven’t returned to the medium, whether because you never got the hang of contemporary controls or you feel alienated by the industry’s penchant for masculinist power fantasies, this might be the game that allows you to see what the medium can do. If you’re someone who does play games, but thinks of them as a minor form of distraction, or even someone who has enjoyed the sweeping narratives of The Last of Us and Red Dead Redemption 2, Gran’s game will expand your sense of the medium’s capacity to tell stories.

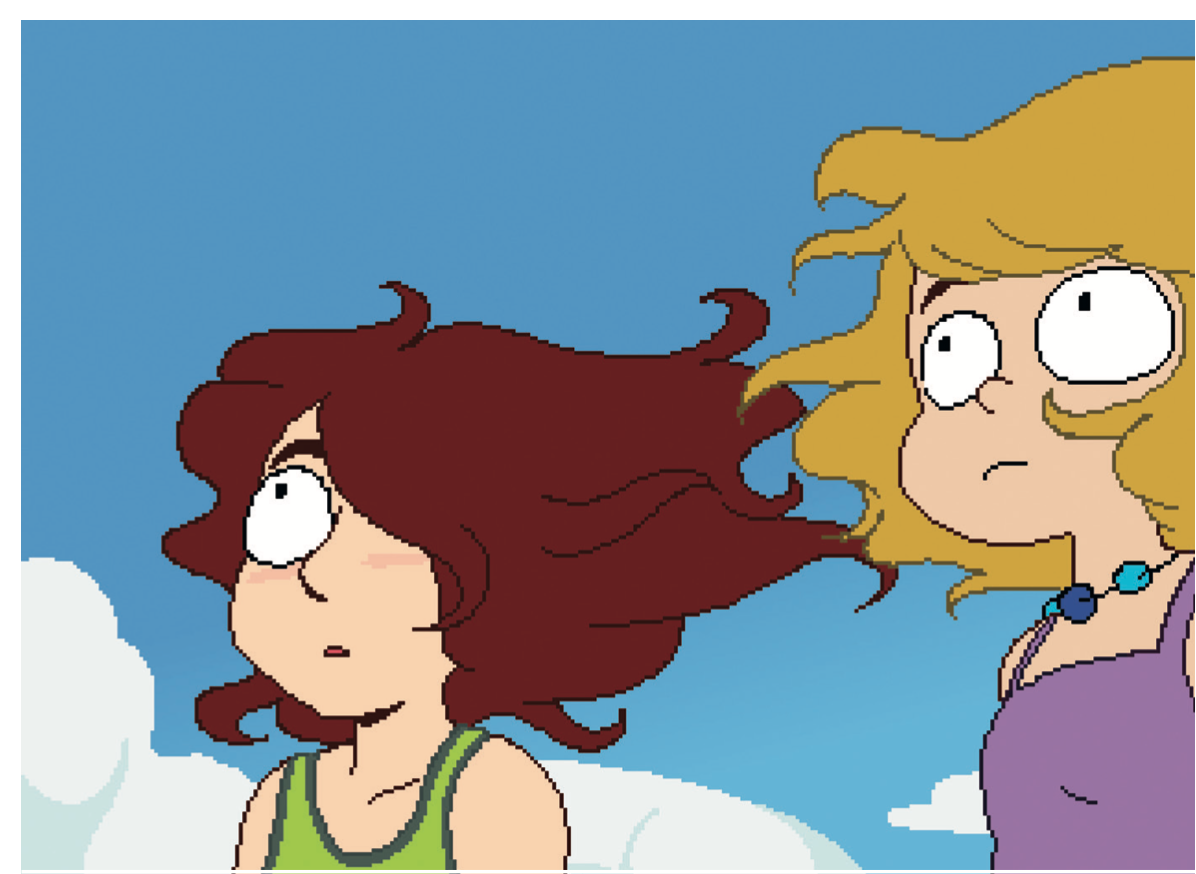

Perfect Tides tells a simple, intimate story about a year in the life of a 15-year-old Jewish girl named Mara Whitefish, in a place very much like Fire Island, New York, in the year 2000. What makes this remarkable is the way Gran fits her story to her medium. Like Art Spiegel- man’s Maus and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home—the two book-length comics that most effectively made the case for their medium to new readers—Perfect Tides reflects its creator’s virtuosic understand- ing of the form and genre she works in.

The specifc video game genre Gran uses for Perfect Tides is the point-and- click adventure, and she draws especially on the Sierra and LucasArts games of the 1980s and 1990s, like King’s Quest and The Secret of Monkey Island. She deploys the recognizable conventions of such games in dazzling ways that seem obvious in retrospect but are, in fact, her own bril- liant innovations.

I’ll give you just a couple of examples. If you ever played one of those old point-and- click adventure games, you might remem- ber that one of their signature ironies is that they’re set in some exciting, life-and-death situation, with dragons or ghost-pirates threatening all of civilization—but, as the player, you inevitably find yourself ambling from room to room, not entirely sure what you’re supposed to do next. (Before inter- net walkthroughs, you could call a 1-900 number for a hint, a facet of the games that became ripe for self-parody.)

Gran understood how appropriate that aimless wandering feels when it works to align the player with an isolated, introspective teenager stuck in a small town. Playing as Mara, a deeply confused and socially awkward young adult, you find yourself walking over and over to the same places, not sure what to do, aching for things to happen—just as so many of us did throughout our teenage years.

Another example of Gran’s virtuosic use of her form is her approach to puzzle design. In many classic point-and-click adventures, the central, often infuriating challenge for the player was to figure out how to manipulate the items in front of them so as to move the story forward. (A classic, genre-defining example: You know you need to shut off a water pump, and you have a banana, a monkey, and a metronome, but what the heck are you supposed to do with them?) In Perfect Tides, most of the puzzles are optional. You know that characters will respond to you differently depending on what you’ve done or not done, but it can be impossible to predict, in advance, what effect your choice will have. This fits the reality of a teenager, whose well-intentioned attempts to impress her friends might backfire miserably, or who might legitimately have no idea what she can get her mother for a Hanukkah present.

Of course, Gran’s bravura attention to form wouldn’t mean much if she weren’t also a sensitive writer of dialogue and descriptions, and an illustrator with a charming visual style. A critic writing for the video game site Polygon rightfully noted that Perfect Tides could be summed up as “devastatingly honest,” and that honesty applies not just to Gran’s treat- ment of Mara’s relationships with her family, friends, and neighbors, her incipient sexual desires and unpleasant experiences, her balancing of life online and IRL, her grief over the loss of her father, and her social awkwardness—but it also plays out in the way the game handles the Jewishness of Mara and her family.

A recent study, by the cultural activist Mik Moore, reported that “poor and working-class Jews are underrepresented” in the contemporary U.S. media—and that makes the Jewish story Perfect Tides tells even more remarkable. Since losing her husband, Mara’s mom barely makes ends meet, and a feeling of being financially strapped pervades the game. Explaining to herself why she didn’t do her homework for photography class, Mara thinks to herself (in the second-person prose in which most of the game’s narration is presented): “You were assigned to buy a camera last month, but you didn’t tell Mom because you knew it was too expensive.” Though she constantly feels the effects of her family’s financial situation, Mara can’t quite wrap her head around issues of wealth and class. One of her friends, an unemployed writer named Simon, lives in a massive beachfront home and she doesn’t question how he can afford it until another friend bitterly poses the question. The game subtly and movingly insists that to understand Mara, we need to understand what it’s like to grow up without money.

Judaism comes up strikingly often: an atheist classmate talks to Mara about her beliefs; Adolf Hitler personifies Mara’s fears and anxieties; Mara teaches a stranger the word “schmoozing”; the holiday of Sukkot is pivotal to the plot. Why would Gran insist on all this Jewish specificity, when so many video games don’t? A partial answer might be found in a moment during the developer’s play-through of the game on Twitch last year.

When Mara gathers with her mom and brother to celebrate Hanukkah at the end of the game, they recite two traditional blessings. Gran had been reading all the on-screen text as she progressed through the game, but she stumbled on the first blessing, the “sh’asah nisim l’avoteinu.” (It’s worth mentioning how poignant this particular blessing might be for a family, like Mara’s, grieving their lost husband and father, as it celebrates the miracles done for our “fathers.”) “I’m no good at this one,” Gran said, on the stream. One of her viewers ribbed Gran good-naturedly in the chat about this: “jewish game dev gets stumped on jewish pronunciation.” Responding, without, as far as I could tell, any defensiveness, Gran mused, “I’m not too different from Mara here. Her understanding of it [i.e., Judaism] is limited, and her connection to it is limited. But there’s a desire to be part of it, anyway.”

What Gran said reflects, more broadly, the autofictional nature of Perfect Tides. She has said that when she was growing up, people called her “Meri,” which is obviously pretty close to “Mara.” The characters, she told an interviewer, are “amalgamations of people I’ve known.” Additionally, Gran has noted that she drew not only on Fire Island for inspiration, but also, in one key moment in the game, “‘the lost ‘Borscht Belt’ of the Catskills,” “a world that was so foundational to” her grandparents. (Not all the details line up, of course).

Like some of the best autofictions, the game commits to a recognizable, sometimes ugly realism. It’s an impossibly rich, remarkably detailed work of storytelling that allows its audience to identify with its protagonist in a way other media forms generally do not allow. No matter how much I read their graphic memoirs, I would never claim I know exactly what it felt like to be Art Spiegelman or Alison Bechdel—and of course I wouldn’t claim I know what teenage Meredith Gran felt, either—but I absolutely was Mara Whitefish for six hours or so, seeing the world through her eyes, feeling her discomfort, making choices for her.

Almost universally, games rely for their appeal on generic sci-fi or fantasy tropes that distract from the human stories they tell. If we’re lucky, Perfect Tides might not only bring new audiences to this particu- lar medium for storytelling, but it might also, like Maus and Fun Home, inspire a future generation of artists to use games to tell their personal, honest stories.

Josh Lambert is the Sophia Moses Robison Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and English at Wellesley College, and author of The Literary Mafia: Jews, Publishing, and Postwar American Literature.