“For Me, Art Has Always Been a Protest”

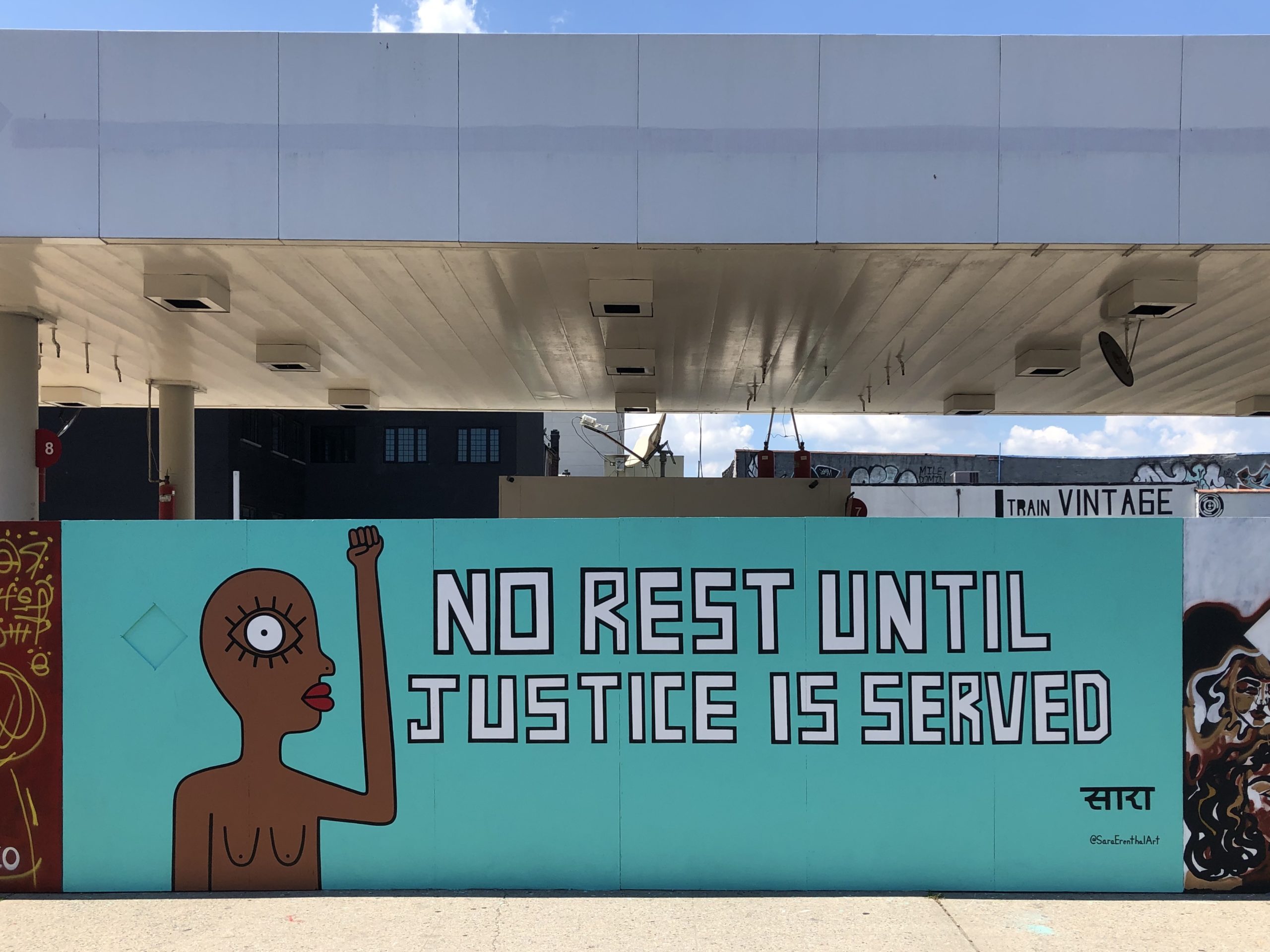

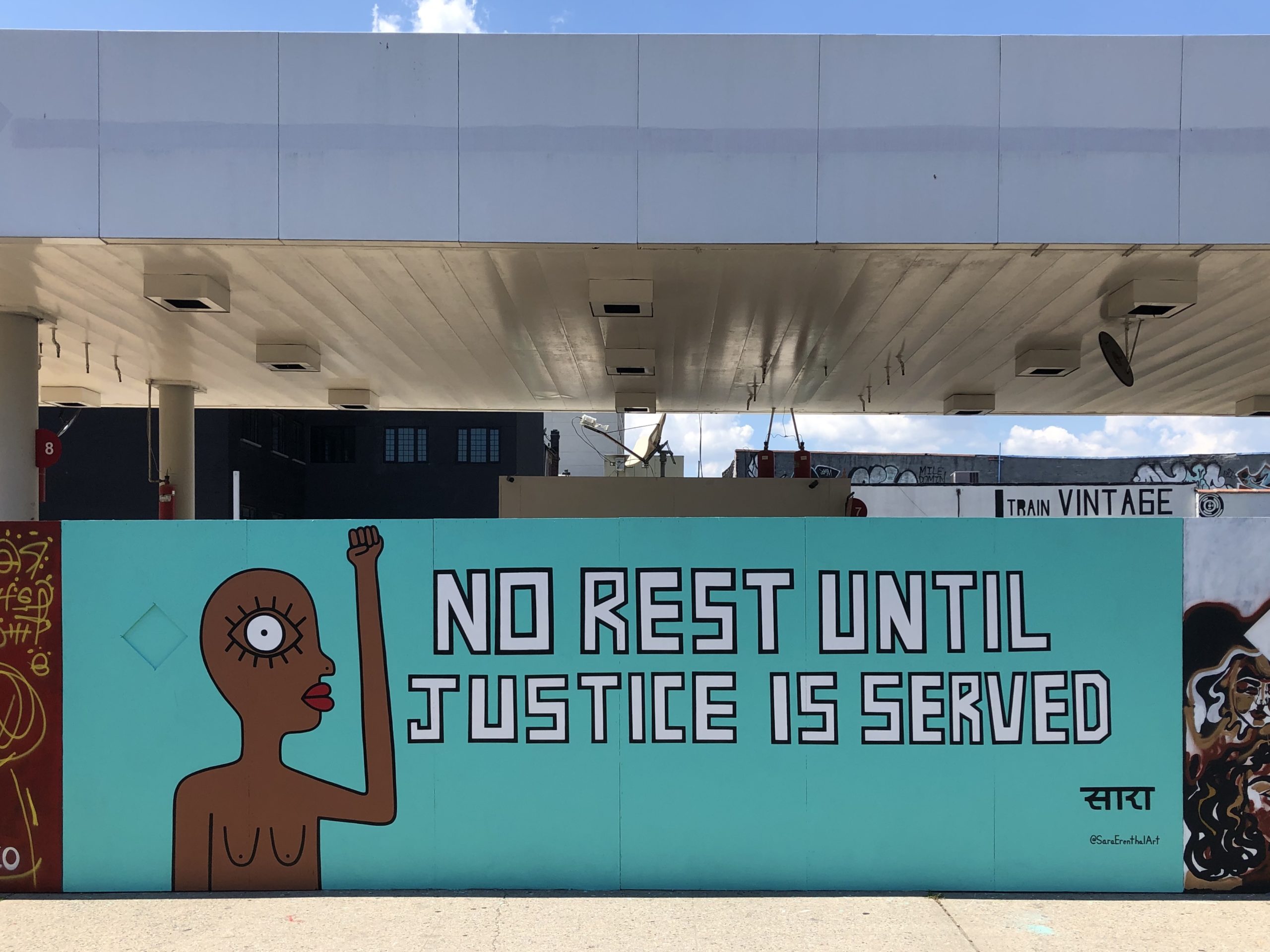

The block-long mural is called the Wall of Justice and it began to take shape on Brooklyn’s Fourth Avenue in Gowanus within days of the police shooting of George Floyd.

“For me, art has always been a protest,” explains multidisciplinary artist Sara Erenthal, who grew up in an extreme Ultra-Orthodox community in New York. “When you make a painting on the street, it’s like screaming out loud. You can make someone feel supported or you can provoke a reaction. I put my message on the Wall—with the words No Rest Until Justice is Served—to show people that racism will no longer be tolerated.”

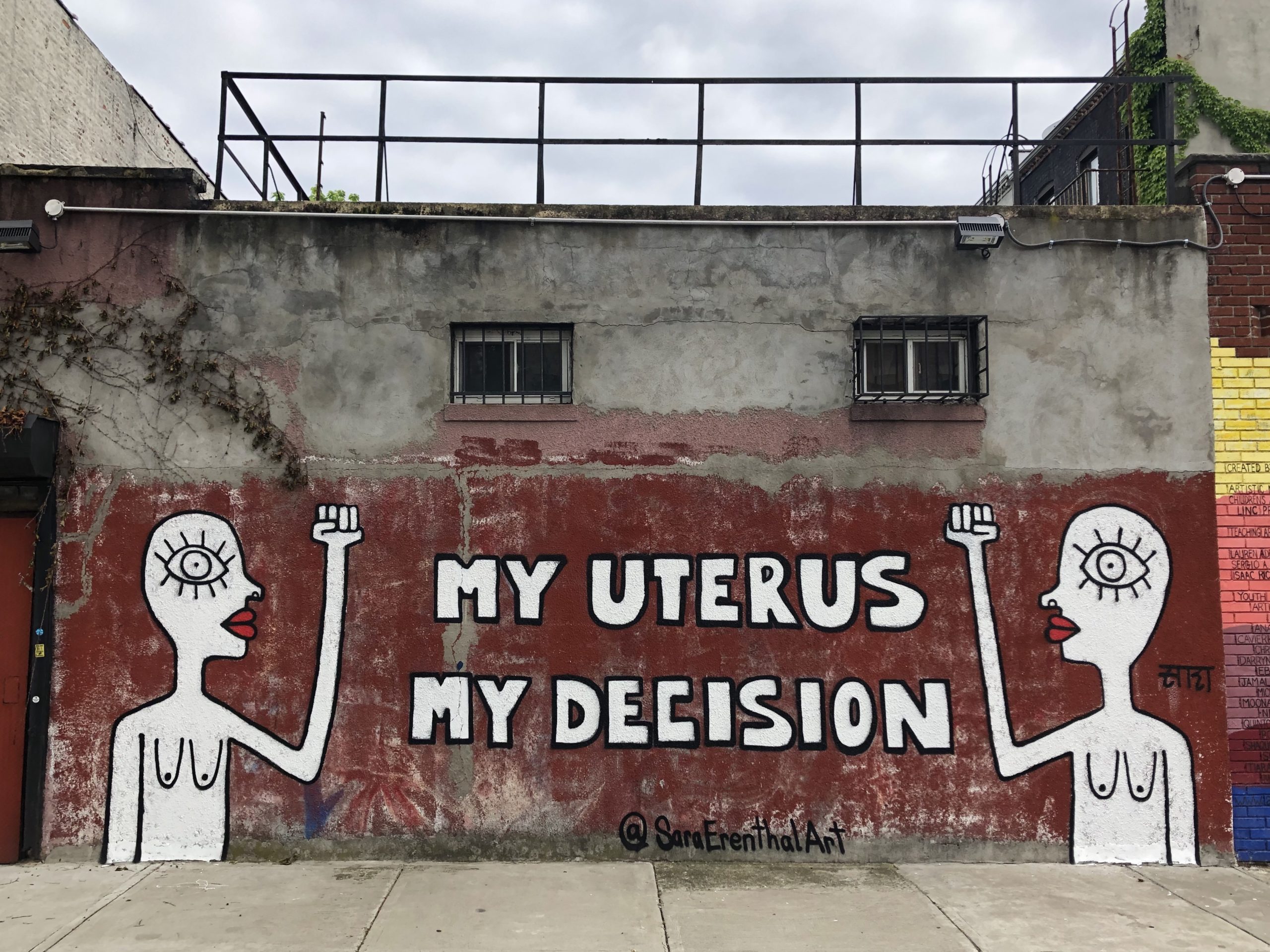

Erenthal’s art typically straddles the line between the personal and the political and can be seen in galleries as well as on the streets of New York City’s diverse neighborhoods. Many of her public works are “self-portraits of sorts,” depictions of a curly-haired, red-lipped female of indeterminate age. Some boast messages: My Uterus, My Decision; Resistance is Female; Children Don’t Belong in Cages, among them.

Erenthal recently spoke with Lilith’s Eleanor J. Bader to discuss her art, her upbringing, and the connection between art and activism.

Eleanor J. Bader: How did you get involved in painting a section of the Wall of Justice?

Sara Erenthal: The Wall was started by Subway Doodle, an artist from Park Slope. Brooklyn. He initially painted the words “Black Lives Matter” on the wall and posted the image on Instagram. The owner of the Wall appreciated the message and gave Doodle permission to reach out to other artists, including me, to see if we wanted to create something in support of the movement.

I’d been participating in the protests but after a few weeks, I decided to put my energy into the mural.

EJB: Can you say more about how and why BLM resonates for you?

SA: I’ve witnessed so many incidents and have seen how African-American people are mistreated. I know the justice system is racist.

As a white person, I’ve smoked a joint on my stoop without police bothering me. But when I see my neighbors of color doing the same thing, the cops often harass them. Worse, too many Black folks have been killed for no reason. It is outrageous, unjust, and upsetting. This is not a new issue. Police murders can’t keep happening. They just can’t.

EJB: Your work has changed over the years from the autobiographical to the explicitly political. How and why did this change happen?

SA: To explain this, I need to tell you about my background, my history. I grew up in an extreme, ultra-Orthodox, cultish environment—a group called Neturei Karta—and had to learn pretty much everything from scratch after leaving the community at age 17.

I was born in Israel, raised in the US, and then returned to Israel at 17 for an arranged marriage to a man I’d never met. After my family left Israel in the mid-1980s, we lived in Borough Park, Brooklyn, and I went to Satmar schools in Williamsburg. When we returned to Israel more than a decade later, I escaped, thanks to help from a friend. I ended up on a kibbutz near Tel Aviv where I was introduced to liberal ideas and progressive people for the first time. I went from a secluded and racist environment to living with people from all over the world. I felt that I’d been given a gift. Still, after spending five months there, I turned 18 and joined the military; I was in the Army for 21 months.

EJB: Were you also making art?

SA: No. You have to understand that I’m completely self-taught. As a kid, I saw my mom make art on-and-off, but I’d never stepped into a museum or gallery.

When my military service ended, I returned to New York. It was 2000 and I had to relearn the City. At the time, I was unaware of politics or movements for social justice, human rights, or feminism.

For most of my 20s, I worked crappy 9-to-5 office jobs. I drew at times but it was a private thing. I didn’t think I had any talent. Nonetheless, I made art whenever I felt strong emotions.

Then, after 10 years of doing administrative work, I got laid off. I put my stuff into storage and went back to Israel. I wanted to take a moment and think about my life. While in Israel, I reconnected with the friend who’d helped me escape and he asked me if I was happy. I said, ‘Yes,’ but confessed that I wanted more. He suggested I travel to India, so I did.

EJB: Wow, that’s pretty spontaneous and bold!

SA: I spent most of my time in India in small villages where life is slow and simple. People are calm. I ended up spending months there. I’d go to cafes where I’d order something and wait maybe an hour for it to arrive. While sitting I had to do something, so I bought some markers, pens, and paper and began doodling. I started to draw girls and women who resembled me and my mother and as I drew, I noticed that I was letting go of stuff.

I spent most of my 20s hiding where I’d come from, trying to be normal. I’d pushed away the negative things I grew up with. As I thought about this it became clear that I needed to deal with my past in order to have a future.

I turned 30 while in India and decided that I wanted to live as an artist. I also knew that I needed to reconnect with the child I’d left behind.

EJB: How did the decision to make art full-time become reality?

SA: When I returned to the US I reached out to Footsteps, an organization that helps people who want to leave ultra-Orthodox communities. I went to them for mentorship and they were great. Footsteps helped kickstart my career. Thanks to them, I had work in an exhibition they sponsored, met people who became my supporters, and got my first press.

EJB: Were you immediately able to support yourself as an artist?

SA: I was definitely a starving artist for a while, crashing with people rather than renting a place of my own. I also worked part-time as a model at the Art Students League and did some dog walking, but I mostly worked in a studio for the first four or five years after I returned. Thankfully, from early on, I was able to sell my work. My biggest supporters are secular Jews who learn about me from Footsteps, Instagram, word of mouth, or through press coverage.

EJB: Let’s go back to a question I asked earlier about how your themes have changed over time.

SA: Initially, my work was just about me, self-exploration, and how my past influenced the person I’ve become.

After a while, though, I began to think about women and how men made all of the decisions when I was growing up. Then—it was pretty amazing, actually—I suddenly realized that I now have a voice and can use it.

I want to emphasize that my work today is still very much about my personal experience, although it now sometimes touches on politics and human rights issues.

EJB: You eventually moved from studio work to the streets and your drawings are all over Brooklyn and Manhattan. How did that happen?

I continue to have a strong studio practice and exhibit my work in galleries, but, yes, I also create a lot of public art. In 2014, perhaps because I am perpetually broke, I started to pick up furniture and other stuff lying on the streets to use as canvasses.

One day I saw a beautiful window pane. It was too heavy to carry home but I drew on it—I always carry markers and art supplies with me—and taped my business card to it. The next day, friends contacted me and said they’d seen someone take the window. I heard that and something in me shifted. I started drawing on discarded mattresses, pieces of wood, furniture, TVs, anything I saw.

A secondary benefit is that I realized that I can save trash from ending up in a landfill by creating art on it.

EJB: How did you begin making murals?

SA: In 2014 or ‘15 I moved into a shared space with lots of other people. I needed solitude and found myself taking lots of long walks. On one of them, I asked the owner of a now-defunct coffee shop if I could paint on the gate. I got permission and made a mural of my three selves: Me as an Orthodox child; me in my 20s; and finally, me as an artist who’s found her purpose.

EJB: You’ve since worked on many murals, sometimes alone and sometimes in collaboration, yes?

SA: Yes. I paint murals almost exclusively on my own, but I have participated in public projects with other artists. For example, right after Trump got elected a friend started a project called Resistance is Female. Artists were invited to express opposition to the new president. Our posters ended up on phone booths and other public spaces. The project gave me a kick in the butt to make more activist art. Since then, a lot of my work has been based on the current moment. I see things going on and make a piece about it, whether it’s an attack on abortion access, police violence, or children in cages. I find making public art liberating and want to use my freedom, my voice, to speak out on these issues.