Twin Sisters Caught in Their Private Web of Words

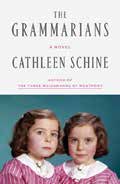

The Grammarians by Cathleen Schine (FSG, $26) is a novel about twin sisters, Laurel and Daphne Wolfe, whose love of words and language cleaves them together as children and ultimately cleaves them apart as adults. Daphne and Laurel, named for the same Greek goddess, grow up playing with words as if they were toys and inventing their own secret language that confounds their parents and their psychiatrist uncle. “Let them go howl in the woods,” says their Uncle Don, who refers to the feral Wolfe sisters as Romulus and Remus. “We revolt you,” Laurel tells him, and Daphne adds, “We are revolting against you.” The identical redheaded twins constantly echo one another and speak each other’s thoughts, not because they read each other’s minds but because they seem always to be thinking alike.

The Grammarians by Cathleen Schine (FSG, $26) is a novel about twin sisters, Laurel and Daphne Wolfe, whose love of words and language cleaves them together as children and ultimately cleaves them apart as adults. Daphne and Laurel, named for the same Greek goddess, grow up playing with words as if they were toys and inventing their own secret language that confounds their parents and their psychiatrist uncle. “Let them go howl in the woods,” says their Uncle Don, who refers to the feral Wolfe sisters as Romulus and Remus. “We revolt you,” Laurel tells him, and Daphne adds, “We are revolting against you.” The identical redheaded twins constantly echo one another and speak each other’s thoughts, not because they read each other’s minds but because they seem always to be thinking alike.

When Laurel and Daphne graduate from college in the late 1970s—the narrative flips past their high school and college years like young girls flipping through the giant family dictionary—they rent an apartment together in the East Village which they refer to as their garret, climbing “linoleum M.C. Escher stairs to live in a tenement their grandparents had probably moved out of the minute they could.” Laurel takes a job teaching kindergarten and Daphne finds an entry-level position at an alternative newspaper, and though neither can imagine enjoying the other’s job, they still occasionally “pull the old switcheroo.” As the girls increasingly individuate, they remain fiercely close, but an undercurrent of competition slowly erodes at their sisterly bond as they start to “elbow each other out of the way in the giant womb of the world.” Laurel, who was born first and has always been the leader, gets engaged to Larry, a wealthy WASP she meets at a party in Daphne’s office, and immediately Daphne finds herself longing for a man of her own:

She wondered if she would ever find someone she cared about. It was so draining, worrying about finding love, as if it were an upcoming exam. She liked sleeping with guys, liked the flirtation and the buildup, the funny awkward dance that led at last to bed. Why was everyone, herself included, so determined to have a proper boyfriend? Everyone wants to be loved; everyone wants someone to love: that was the reason, obvious and bland and thrilling and eternal. God, it would be so nice, so restful, to call off the search.

Instead of calling off the search, Daphne scrambles to find a husband, breaking off an engagement with one guy in time to marry Michael, a nice Jewish doctor, in a double wedding with Laurel and Larry. Laurel is first to become a mother, though each twin has one daughter and in this, too, they mirror one another. Daphne, who now has her own popular newspaper column called the “People’s Pedant,” is scornful when her sister quits her teaching job to be a full-time mom; she is equally dismissive when Laurel starts writing poetry that appropriates sentences and phrases from historic correspondence. “Neither Laurel or Daphne were famous… no one recognized them on the street. They could not get restaurant reservations anyone else couldn’t get. But in the world of words in New York, they were known.”

Also known in the world of words in New York is Cathleen Schine, many of whose novels chronicle the family dynamics among New York Jews in the latter part of the twentieth century. Schine has a keen ear for dialogue, and this novel, like her others, thrives on the wit and banter of her characters, whose love of word games lends the book a playful, comic tone that never ceases to delight. And yet there is something superficial about the twins’ obsession with language; as their cousin Brian, son of psychiatrist Uncle Don observes, “a cloud in the sky was of real interest to them only when they were told it was a cumulus cloud and that ‘cumulus’ meant heap in Latin. In their way, Laurel and Daphne were as fatuous as his father, he had realized.”

Laurel and Daphne love words – not sentences, not paragraphs, and not books. But what delights us on the level of the word is not always moving on the level of the sentence, and is not always arresting on the level of the paragraph, let alone the book as a whole. By the novel’s end, I found myself as exasperated with the grammarian twins as they grow with each other, wanting to grasp and shake them and speak the same words their mother tries to convey to them: “No, you are missing the point. There is no word, just words, lots and lots of them, a universe of words, galaxies of them.”

Ilana Kurshan is the author of If All the Seas Were Ink, winner of the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature and available in paperback from Picador.