Dara Horn

Dara Horn is 26 and lives in New York City. Her novel In the Image (W.W. Norton) was published last fall. [See page 29]

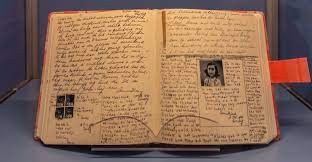

I read Anne Frank’s diary when I was 12, ravenously, because I was a journal-keeper myself. But in the end I didn’t love the book the way every other 12-year-old did. I felt guilty about it, but what prevented me from loving it was precisely the reason every adult in the world expected me to read it—that third-to-last diary entry, where she writes: “in spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart.”

There is something cheap about that ending, and I think I sensed it even then. It’s not just that it turns an intelligent person into a symbol for what we think children are. This idea turns the book’s lasting impression into, at best, a crudely sweet sentiment, or at worst, a lie.

It has been observed, with irritating irony, that Anne Frank would never have achieved such profound success as a writer if she hadn’t been murdered. Fair enough. But the most vital form of success a writer can achieve is not fame at all, but prophecy. Not prophecy in the sense of predicting the future. Prophecy in the sense of telling people what they absolutely need to know, particularly when they don’t want to know it. Most people who comment on Anne Frank’s posthumous success imagine an alternate world where she would have grown up peacefully, settling into a career as a Dutch journalist or novelist, perhaps a writer of interesting insight, but little more. The alternate life I imagine for her, however, would have been far more likely.

The writer I envision is someone who survived Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen as a 15-year-old girl—someone who saw pits of burning bodies and babies shot in the air, someone whose head had been shaved and whose skin had been permanently tattooed and who had watched her mother and teenage sister rot to death, who had withered away to a skeleton and would likely rip someone’s face off for another crust of bread, someone who spent an entire teenage year inhaling smoke made out of the bodies of her family and friends—only to be “liberated” at 16 into a world of yet more camps, refugee camps, displaced persons camps, until she was at least 18, and then (possibly infertile, possibly disfigured, possibly disabled, definitely mentally older than the oldest person alive) forced to return to a country and a language in which she no longer has anything to say or anyone to say it to, or worse, becoming bereft of her language, forced to move to a new country and a new language different from the one in which she had lived her life and her near-death— a person who, while spending every night screaming through nightmares and every morning ashamed not to wake up dead, at last has no choice but to turn to prophecy.

Would this be a writer who would vow that “in spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart“? Possibly. But I still believe, in spite of everything, that she might have had a whole lot more to tell us.