Anne Frank Behind the Iron Curtain

In 1960, U.S.S.R. authorities decided to “import Anne Frank’s diary, perhaps the only Holocaust document that managed to break through the “Iron Curtain.” Ironically, according to official Soviet history, the Holocaust as we know it—the mass murder of Jews only because they were Jews— did not happen at all. The U.S.S.R. authorities believed that Soviet Jews were murdered by Nazis not because they were Jewish, but because they were Soviet citizens.

Admitting that Adolf Hitler considered the Jewish people the Nazis’ main target would lead to another, much more dangerous idea: maybe there was something mysteriously good in Jewish values, something that made the very existence of Jewish people threatening to the absolute evil the Nazis represented. How could Communist leaders accept this when, according to their ideology, absolute good could be represented only by the U.S.S.R.—the most progressive country in the world?

The year 1960, when The Diary of Anna Frank was first published m Moscow, was the culmination of a period in Soviet history when ideological clutches were loosened. For Soviet Jews, a short break between two major anti-Semitic actions launched by the Kremlin: the infamous “case of medical doctors” and the rise of the anti-Zionist movement after Israel’s Six Day War Jews were relatively free of fear, guilt and shame then: they were no longer identified with the “killers in white medical gowns,” and not—yet—with Zionist aggressors that had trodden “friendly Arab people” under their iron heel.

During this “thaw,” Soviet values became more liberal, more respectful towards individuals. One could allow herself or himself to be not an ideal Communism-builder, an ordinary human being with a complex nature and a wide spectrum of feelings.

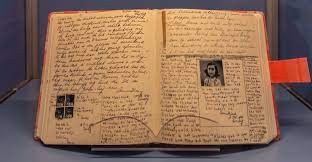

Anne Frank—a young middle-class German Jewish girl killed by Nazi evildoers, Anne with her rich inner world, sweet weaknesses and literary talent—ideally fit into that newly admissible model of a human being.

Still, I think, Kremlin leaders hoped that their subjects would not feel sympathy and compassion for Anne. They hoped, on the contrary, their subjects would regard Anne as a spoiled bourgeois brat who dared to complain when she should be grateful for not sharing other Nazi victims’ (especially Soviet people’s) terrible lot.

Anne Frank was let though the Iron Curtain for the wrong political and ideological reasons. But the reasons she was welcomed into the hearts and minds of Soviet Jews (and Soviet people in general) were not wrong at all. She won our hearts with her personality, her talent, her vulnerability and her tragic fate. Moreover, it was Anne’s “poisonous” influence that made us, Soviet Jews, start the long journey towards our heritage, towards discovery of our real role in World War II and in human history in general. Maybe it was Anne who, in the end helped us break through the Iron Curtain, or even to break the Iron Curtain itself.

Leah Moses (Moshiashivili) was born in Tbilisi, Georgia, former U.S.S.R. in 1953. She has lived in the U.S. Since 1994. She is a staff writer for Russian Jewish Forward.