Diane Mehta’s Miniaturist Poetry

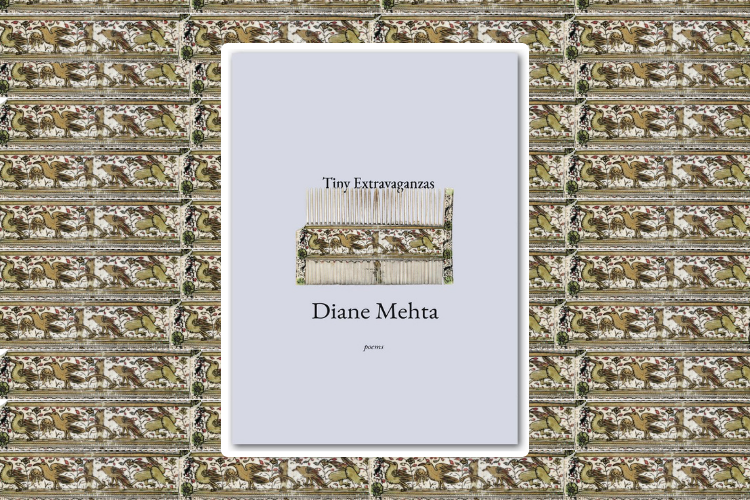

Tiny Extravaganza (Arrowsmith, $20), Diane Mehta’s lyrical new collection, works the American sentence to its limits. Mehta’s poems are miniaturist examinations of art, aging, literature, grief, parenting, the sublime, labor, and faith. She talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how the crafting of poems both feeds and is fed by everything she does.

YZM: You’re a poet, novelist and essayist; how do these three forms of expression feed and nurture each other?

DM: Each form enhances the others in ways I don’t expect. I write rhythmic and lyrical poems, and my mind is associative, so I learned to put those skills to work when writing essays. It took me longer to recognize the ways in which writing a novel taught me to tighten the structure and avoid detours in poems or essays.

The connective tissue that ends up combining line, diction, dialogue, meaning, and motivation is the same in every genre. Each line has a pace and rhythm, each sentence earns the next, and every paragraph defends the one above and leans into what comes next. I’ve gotten closer, over time and practice, to creating a single motivating narrative for each type of writing. In other words, I’ve become more precise and aware of a creative work as orchestration, with setup, motifs that wander and resolve, and a scope that builds over 20 lines or 200 pages. A neat way of thinking about it musically is that poems resembles the sonata form, essays the quartet, and the novel a symphony.

The process of writing poems has taught me that everything takes shape over time. I’ll spend ages on just a few lines in a poem, and grind forward if I sense it’s going to turn into something. If I can get a poem to move, I can get jumbled or ineffectual prose to move. I used to improvise more, catching a rhythm or an idea, and let loose with my imagination. The decades have proved to me that it is only possible to create the illusion of a tone that is improvisational. I don’t mind, because the work of figuring out which techniques operate to my advantage in each genre broadens my skillset and makes me more tactical. The advantage of being a poet doing other work is to recognize that I can write sentences that are unlike other people’s sentences, and this propels me forward when other parts of the writing process, such as dialogue or scene-building, don’t come as easily.

YZM: Do you feel your Jewish background informs your work and if so, how?

DM: It operates on an intellectual level, below the surface of the sentence and mood. Faith is in doubt in many of my poems, though it is through my obsession with Italian medieval and Renaissance paintings, and their Catholic subject matter, that questions about faith present themselves. In my mind, I don’t distinguish between Christian and Jewish theological concerns, because they are monotheistic religions touting stories of prophets who struggle with faith, and it is the struggle that interests me.

I identify with the wandering Jew, the faithless Jew, and the uneasy Jew who, like all good Jews, interrogates God and myself. This is the function of Talmudic debate, the work of learning to ask good and better questions, and figuring out how to be a mensch: paying careful attention to ideas and to people, being an ethical person and a good parent, paying witness, and learning to forgive. Perhaps it is unconventional to say that the poems are inherently Jewish even with no ostensibly Jewish “content,” but I don’t feel conflicted about it. These poems are in conversation with other artists, with stories in the Old Testament, and with readers. The intellectual space in which I exist is primarily Jewish.

YZM: Certain themes recur in these poems—a few are birds, trees and…cake! Can you elaborate on these themes and why you returned to them?

DM: Each is emblematic of a conversation I’m having with myself about love and death. Keats’ nightingale is always in my head: “Thou was not born for death, immortal bird!” says the speaker, who hears the singing and briefly feels terrific before sobbing that life is short. Birds and trees have always been about hope, uplift, regeneration. Birds migrate, trees shed their leaves, the landscape regenerates. Along the way, we have cake for comfort and celebration! It’s a way to mark human time and an occasion for connecting to others. Of the three cakes in my book, two are counterpoints to grief, even while grieving, and the third is about sharing a meal with a group of artists in Italy—a celebration of conversations to come.

I’m tuned into the ways that the natural world punctuates my days: leaves rattle in a storm, a nest falls onto the street, newborn leaves pop up in fluorescent yellow-green, an unfamiliar bird screeches in the yard. I try to respect the presence of other species in my surroundings, and their role in sustaining the planet. I don’t understand bird psychology or what their noises mean, and I can’t begin to contemplate the cooperative relationship between trees and fungi that twine around their roots, or their belowground resource sharing, but I know how to recognize my limits. I have a poem in the book about a relationship with a cypress tree that speared the air outside my window in Italy. Days, I worked with the window flung open. Periodically I’d turn and gaze out at the firm cypress standing there, eyes fixed on me. During a hoary storm that flew down from the Apennines one night and rattled me, I flung the shutters open and saw the cypress bending this way and that, and it seemed to twirl the wind in a pas de deux. It had this primal, magical power, and a whole other life that I was lucky enough to see.

So I’m hyperattentive to what other species do on their own time. Flight is the most appealing of all gifts, and the aerial view, compared to ours, is precise, and blows open our biases and localized judgments. This is what Wallace Stevens captures so efficiently in Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. There’s what we see, and all the possibilities for what we must train ourselves to see.

There’s also just the way these uncanny bird-creatures scissor across the sky, switchback or ride the air, track their meals, and harpoon the meat. Who knows what they’re thinking! But Walt Whitman’s “uncaught bird” (in Song of the Universal) steals your breath—“hovering, hovering, / High in the purer, happier air”—and you sense the thrill of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ in The Windhover watching a falcon veer around the sky. We’ve got hang gliders, planes, rockets, and I wonder if we’re always crossing a line, chasing more knowledge, more excitement. In Greek myth, and in Homer and Dante, flying is metaphor for the hubris of trying to travel beyond our human limits. Think Icarus’s wax wings and half-mortal Phaeton’s fatal attempt to man the chariot of his father, the sun god. Poets lounge under trees, writing about the landscape, perhaps because we are seeking to catch what we cannot—to cross species, to believe that our days are meaningful.

YZM: The last line of the poem “Nothing Doing” is Art diagrams the measure of all we find; that’s a powerful sentence; can you talk more about what it means for you?

DM: The work of discovery is the discovery, in writing and in life. Perhaps my world has become narrower, but it seems that the work of art, and of thinking about how it conveys meaning or embodies meaning, has become far more important than more traditional measures of a life. I wonder if my greed for a finished product harms my ability stay in the moment. After the final draft, I feel utterly pleased with myself. But if I measure myself against the feeling that propelled the poem, the feeling is over. Is the poem over? We are all so focused on the product—a good poem, stacked accolades as proofs of a good life. But every measure is a little untrustworthy. So I defer to Art as a more reliable way to diagram what I care about and how much I put into my work. I’m also interested in the idea of duration, and discovering something through labor.

The French poet Paul Valery believed the poem itself was the act of writing it, so by his measure, the poem is over, ruined, dead, once it becomes fixed and published. The way to actually write a poem, he suggests, is to assemble and dissemble and reassemble it, and that is the measure of art—something alive, not the finished poem. I explore this concept of immersive experience in a poem about Willem de Kooning’s Woman I, a painting at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Years passed while he painted, scraped, and repainted the painting, and generally messed with the canvas. The subject, a hefty middle-aged woman, is fierce. I’m not sure he meant to finish it. So what is it worth now? Tens of millions, probably. I wonder about “value” a lot, and think that deKooning, Valery, I—anyone creating serious work—recognize the value of being inside the work. We continue to create value is through the conversations it spawns with oneself and with others. If I’m a reader paying close attention to a poem, I expect it to diagram an idea or situation for me, but I expect to work for it, too. There’s the mechanical blueprint of its parts, and the ways they move together. Is it something unusual? What happened inside that poem, inside that canvas?

YZM: What’s next for you?

DM: I’m midway into a poetry cycle connected to Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy, which I’ve been reading on a loop with a porcelain artist and a cellist I met in Italy. In parallel to Dante’s friendship with the poet Virgil, in the book, we’ve developed a deep artistic friendship. Reading Dante has made me more ambitious as a poet, in line with Dante’s own ambition. He had a crazy amount of ambition, talent, and imaginative scope. He wrote a 10,000-line poem in a pulsating new rhymed form, and in vernacular Italian instead of Latin, the elite language of the time, and he did all this under great duress while exiled from Florence. Instead of succumbing to his misery, he gathered up his resources (it took a few years) and wrote a love poem to a girl he met once, about the journey of becoming a better person.

So my work around Dante is about cultivating friendship and excellence, learning to experiment with poems that are ambitious in mechanics and scope, and figuring out how to receive or give more love than I am already capable. This is at the heart of Dante. My poems respond to Dante’s characters and their situations, and riff on or argue with his ideas in a contemporary idiom.

This Dante project, and the cellist in my group, have fed my interest in music, and in response I’ve begun collaborations with musicians to weave poems from Tiny Extravaganzas into improvisational music. It has created an ear-opening space for working with musicians and experimenting with the timbre of my own voice.