“The Archivists” Dives Beneath the Surface

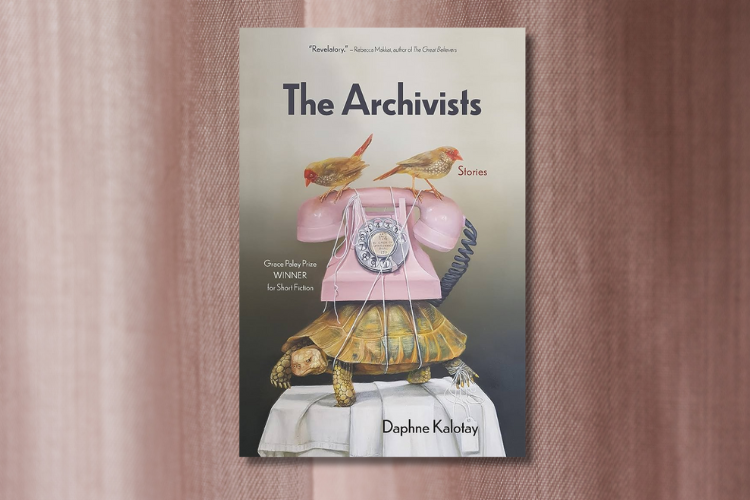

The characters in The Archivists (Northwestern University Press, $20) may seem like ordinary people but author Daphne Kalotay dispels this notion, deftly revealing that there is so much more that lies beneath the surface. She talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the surprising and often poignant ways these individuals find connection, meaning and even redemption.

Yona Zeldis McDonough: You’ve written about the ways in which Jews often changed their last names to mask their religious affiliation—including how the name Kohn became Kalotai. Is this a reference to your own last name and if so, why did you include it here?

Daphne Kalotay: Yes, this is a reference to my father’s last name; the spelling of Kalotai was changed when the family immigrated to Canada. In a way the inclusion of this detail marks my own transformation as a writer who has become more willing to delve into my family’s stories and acknowledge my own connection to the themes that preoccupy me. In the past, I was uncomfortable going to these difficult personal places and always slightly altered that connection. Earlier published versions of the story you refer to maintained anonymity by using not “Kalotai” but “Kopp.”

It was only as I prepared the manuscript for this final iteration—the book version—that I realized I wanted to reclaim the true name change and have it on record. After all, that’s in part what the book is about: the way these facts are lost over time. Other last names in that list come from other family members whom I knew by those assumed names. Only much later did I learn their original last names—for instance, on a visit to Hungary when my sister and I went with our father to the Jewish cemetery and saw the names on the gravestones.

YZM: Can you discuss the way elements of realism have been woven into the stories “Heart Scalded,” “Awake,” and “Communicable”?

DK: I actually view each of these as realistic stories—ones in which phantastic elements simply happen to assert themselves more strongly than we are accustomed to allowing into our daily lives. Perhaps a more accurate description would be to say that in these stories the protagonists, because of what they’re going through, are particularly attuned to the “magical” elements that emerge—but to me it seems there is in fact a perfectly logical explanation for everything that occurs. This is to say, the everyday circumstances we can find ourselves in (like the woman at the party in “Heart-Scalded”) and the more insidious situations we create around us (as in “Communicable”) can be just as “bizarre” as any supernatural event. Sometimes in my writing the external manifestation of these conditions results in something that seems beyond real—but I think that if you’ve ever, for instance, felt truly depressed, confused, or disoriented, a story like “Awake” is very real.

YZM: The idea of archives is referenced in the collection’s title story and then again in the story “Oblivion.” What does that term mean for you and why is it important?

DK: I think that many of us who write do so out of an almost obsessive fear of losing the past. We keep journals to record the details of what we observe, hear, experience, and diaries to mark the days. Even then there’s a churning inside, that urge to transmogrify, to make of the days, the snippets of conversation, of observation, something beautiful and lasting. For me this urge is very much connected to family history and the fact that one side of my family was practically wiped out. The sense of loss is palpable; one is raised with an awareness of this thing that happened, and the thing is often expressed not only as who was lost but what. The items that were buried for safekeeping, the silverware, etcetera, stolen by the neighbors…. We construct our own stories through belongings, through documents.

When my father emigrated from Hungary, his stepfather, a physician, insisted on bringing along the medical journals in which he had published articles; this was his way of insisting on who he was, beyond a refugee. So to me the idea of archives comprises not just actual physical containers of evidence but any of the things we do—like the dancers and others in the story “The Archivists”—to convey truth to others. The stories we tell, the art we create.

YZM: Many of the stories deal with loss—of a child, of love, of a sense of safety in the world; care to elaborate?

DK: Life is about loss. If you love, you will eventually experience loss. I wanted to write stories expressing the beauty of this fact, rather than wallowing in sadness. In 2015, I lost one of my very closest friends. I miss her every day. But that grief is also an acknowledgment of the power of our friendship—and many of these stories celebrate her qualities. She was an environmentalist and very preoccupied with the ruination of our planet. So that aspect exists in the stories as well. But my aim was to write these not from a place of moroseness but rather with an eye to the inherent absurdity in this situation we call the human condition.

YZM: What are you working on now?

DK: I’m working on a new novel that is also inspired in part by my family. I’m too superstitious to say anything more.