“Cradles of the Reich” Examines Complicity

At Heim Hochland, a Nazi breeding home in Bavaria, we meet three very different women. Gundi, an Arayan beauty, is a pregnant university student from Berlin. She’s also secretly a member of a resistance group. Hilde, only eighteen, is a true believer in the cause and is thrilled to carry a Nazi official’s child. And Irma, a 44-year-old nurse, is desperate to build a new life for herself after personal devastation.

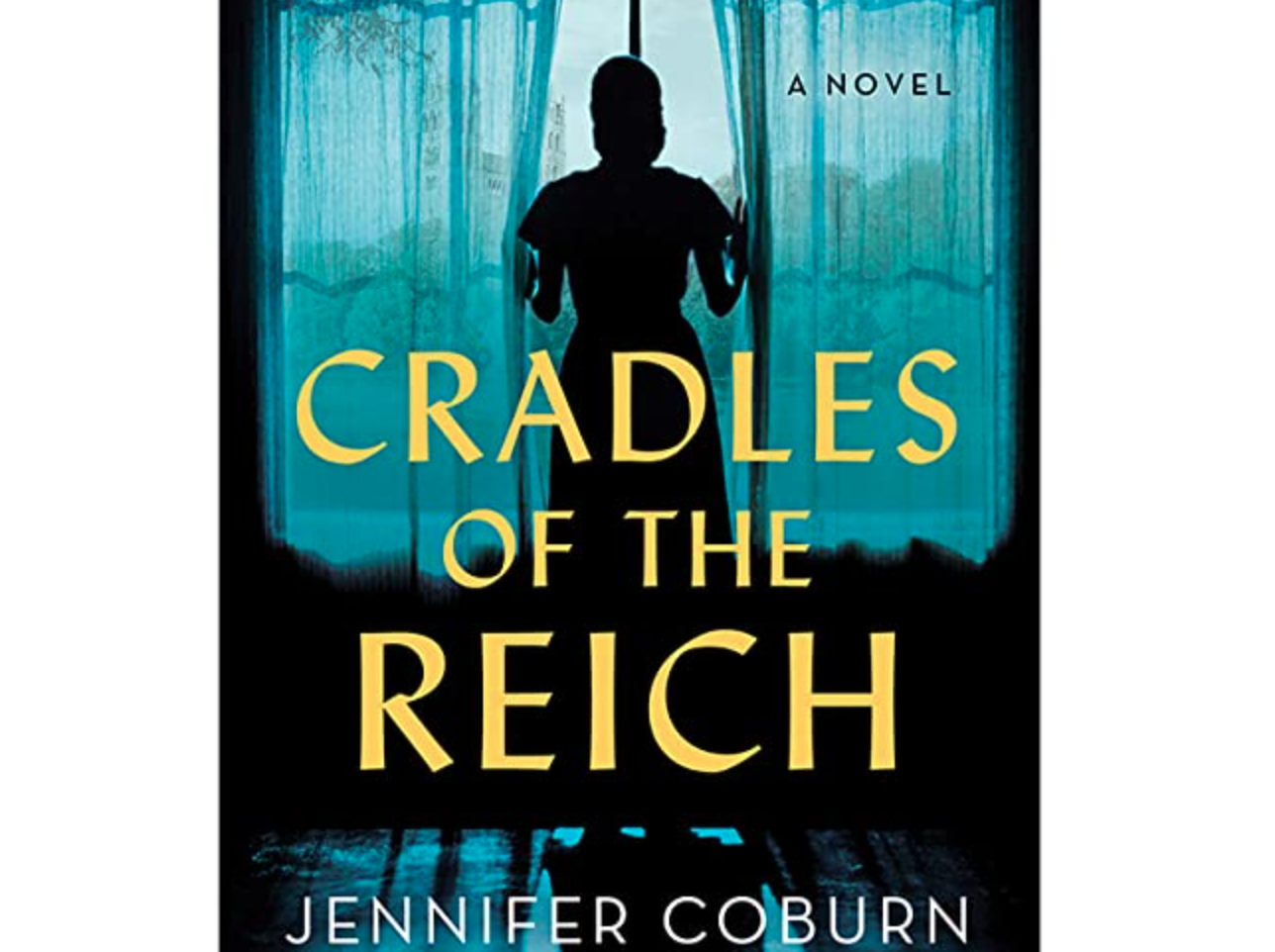

Based on actual historical events, Cradles of the Reich (Sourcebooks, $27.99) brings us intimately inside the Lebensborn Society maternity homes that existed in several countries during World War II, where thousands of “racially fit” babies were bred and taken from their mothers to be raised as part of the new Germany. Fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks with novelist Jennifer Coburn about her journey into this dark chapter in a very dark past.

YZM: How did you first learn about the Lebensborn program? When was it started, how long did it continue and how many such homes were there?

JC: A few years ago, I watched an Amazon series called The Man in the High Castle, based on the Philip K. Dick novel, which brought to the small screen my worst nightmare as a Jewish woman. An alternate history, the show is set in the 1960s after the Germans have won the war and most of the United States is part of the Reich. When a character mentioned she was bred through the Lebensborn Society, I figured this was a fictional element of the show but looked it up out of curiosity and found that it was a real program. I was floored!

I had so many questions: Why would a young woman volunteer to have sex with a stranger and give her child to the Reich as an act of patriotism? How were the women selected? Did their parents know what they were doing? Was the program successful? And finally, why had I never heard about the Lebensborn Society before?

This top-secret society began in 1935 as a maternity home for single mothers with Aryan pedigree and a breeding program for German young women. That is to say, the program arranged sexual liaisons between “racially valuable” German women and SS officers. When the war began, the program expanded to include kidnapping Aryan-looking infants and toddlers from in Nazi-occupied countries.

In its ten years, somewhere between 26-32 homes were in operation and had produced nearly 20,000 children. The Nazis stole 200,000 infants and toddlers, 100,000 from Poland alone. The Nazis burned thousands of records at the end of the war so exact numbers were impossible to find. Every time I thought I found a definitive answer, I soon discovered conflicting evidence.

YZM: Is there information about how many babies were placed with German adoptive families? Did any of them ever seek information about their birth parents?

JC: About eighty percent of children adopted through the Lebensborn Society had no idea they had been part of this program. Plenty went to their graves never knowing that they were kidnapped, adopted, or bred. Many of those who discovered this were eager to trace their roots. These adult children have formed support groups to address the trauma associated with being tied to the Reich this way. The most famous Lebensborn baby is Anni-Frid Lyngstad from the pop group ABBA.

YZM: Did these homes also function as brothels and if so, can you say more about that aspect of them?

JC: Women who were racially screened for pure Aryan pedigree could volunteer to have “a child for Hitler” by becoming pregnant with the child of an SS officer or German soldier. Most often these men were strangers but on rare occasion, the German women and officers fell in love and married. Hildegard Trutz was a German girl who lived at a Lebensborn home and, in an interview, recounted her days in the program as the best of her life. She raved about the food and the lack of work. Trutz became pregnant with the child of a soldier she met only once and never saw again. Nine months later, her child was adopted by a “good” German family. Some historians dispute the breeding element of the Lebensborn Society, but I had to make a choice when writing this novel as to whether to believe the testimony of Trutz and other accounts that the program was a brothel of sorts. The question I asked myself was: Knowing what we do about the Nazis, do I really believe that breeding is where they would draw a moral line? The answer was a resounding no.

YZM: When Irma sees the engraved initial on the tray, it makes her think about how the tray was obtained; why is this the first time such a thought occurs to her? Later in that chapter she has another realization about the plight of Jews under the Nazis; can you talk more about her transformation?

JC: Like many Gentiles in Nazi Germany, Irma was initially indifferent to the plight of the Jews. Antisemitism was so pervasive that the disenfranchisement of the Jewish people wasn’t that shocking to her. Irma is a character who is particularly cut off from her feelings because of past trauma from World War l, so she just wants to keep her head down and survive. In her time caring for the young women at the Lebensborn home, the nurturing, caring part of her is reawakened and that changes everything. Now when she sees initials engraved on a silver tray, she wonders who it belonged to and what happened to its owner. It was her wakeup call and from there, Irma Binz can never go back to being the callous person she once was.

YZM: Hilde, one of your protagonists, has bought the Nazi party line through and through and she never budges; was she a difficult character to write?

JC: Extremely! As a Jewish woman, it was a real challenge to write from the point of view of someone who considered my family sub-human and unworthy of life. Still, in order to develop the character, I tried to dig in to what drove her. I tried to develop a character who is complex and layered without making excuses for her abhorrent behavior.

YZM: Each of these women represents a different attitude toward and has a different relationship with the monstrous Nazi regime; can you elaborate?

JC: Each of my three protagonists represents a facet of the Gentile German population. There’s Gundi, the resistor, Irma, the indifferent, and Hilde, the true believer.

A novel is driven by conflict so if I put three women with completely different outlooks on life and desires, I knew sparks would fly. In the end, each character doesn’t necessarily get what she wants, but they all get what they need.