I Am Russian… In Name Only

This weekend, I scrolled through the New York Times, flinching from images of pregnant women on stretchers with the rubble of battle behind them. I found Jeremy Peters’ article “That Russian Business You’re Boycotting Isn’t Actually Russian” and I finally exhaled. At last, coverage instead of virtue-signaling. To recap: bar owners are boycotting Stolichnaya (a vodka produced in Latvia), patrons are avoiding the Russian Tea Room (a restaurant established by a Polish immigrant in New York City), and callers are pestering the Red Square (a bath house in Chicago co-owned by a Ukrainian) to… take a side.

And my friends have been asking me… what do I think about the conflict in Ukraine? As a Russian. Well, first things first: it’s sadly obvious why these businesses are being targeted. They are Russian… in name only. And why did they choose Russian names? I can’t speak to each business individually, but I imagine it’s because that’s what sells. Many Americans today are still products of the Cold War, still more familiar with Russian-ness in the form of Boris and Natasha from the Rocky and Bullwinkle Show than Boris Pasternak’s struggles in the same years.

I am not Russian, but I speak Russian. It’s a kind of nonconsensual tattoo Stalin left behind on my parents—better tattooed than dead.

I haven’t read Doctor Zhivago—the book he wrote in 1957—but I watched the strangely cold and boring movie because Omar Sharif (known to me as Yentl’s boyfriend from Funny Girl) was in it. I remember the fabulous winter coats and my father telling me about Pasternak’s “winning” of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958. Soviet publishers vehemently rejected the book for its poor adherence to socialist principles, but then a press in Milan picked it up. It was an instant hit in the West and condemned in the USSR. Pasternak hoped he wouldn’t win the Nobel Prize lest it put his family (and self) in danger, so upon winning, he declined: “In view of the meaning given the award by the society in which I live, I must renounce this undeserved distinction which has been conferred on me.”

How about that for a euphemism? “In view of the meaning given the award by the society in which I live.”

I think about this a lot. And I’m thinking about it again: the sprawling idea of “Russia,” the black hole out of which artists and scientists crawl against all odds and never look back, the bottomless pit of cartoonish accents and fur hats. My first language was Russian, and I don’t know what to do about it anymore. It’s the language of the oppressor of my ancestors: what does it help me understand? It is also the language of Chekhov, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Yevtushenko, Akhmatova… and the best way to communicate with my parents. Think about all the Jews you know who can’t read Hebrew: it’s a bit like that but the other way around. I am not Russian, but I speak Russian. It’s a kind of nonconsensual tattoo Stalin left behind on my parents—better tattooed than dead.

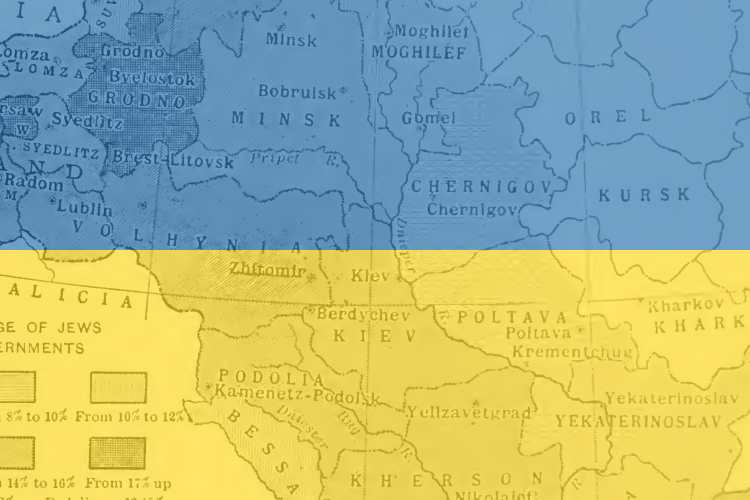

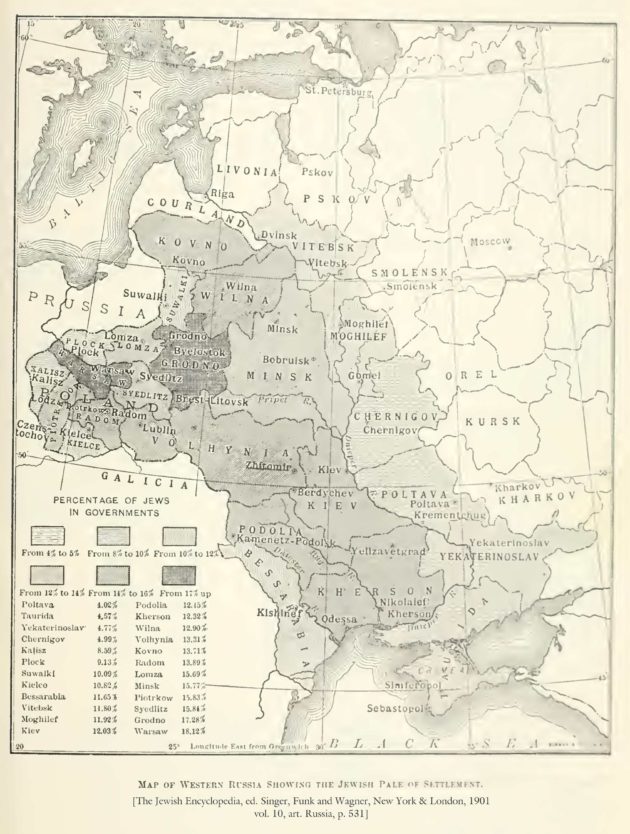

Furthermore, there’s nothing Belarussian or Azerbaijani about my parents, either, because their parents grew up in the Pale of Settlement… the parts that became modern-day Ukraine.

And there’s nothing “Russian” about my parents: my father grew up in Belarus, and my mother grew up in Azerbaijan. These are two countries with their own languages and cultures. Furthermore, there’s nothing Belarussian or Azerbaijani about my parents, either, because their parents grew up in the Pale of Settlement… the parts that became modern-day Ukraine. Oh, and there’s nothing particularly Ukrainian about that generation because they were Jews, painfully separate and aware of the distinction. I guess you could call Pasternak Russian because he was born in Moscow, but his parents, a painter and a concert pianist, were assimilated Jews who claimed to be descendants of a Sephardic Jewish philosopher. He was baptized, later insisting that it was better for Soviet Jews to convert to Christianity than to accept Stalinist atheism. Choose between an invisible deity and a visible dictator. My mother did not write banned books, but she still walks into baroque churches with awe, tilting her head back and marveling at the space left for any God at all.

As of eighteen days into the war, my Papa says Putin can’t win because “every Ukrainian will shoot him from their balcony.”

My father is a bit of a Luddite—he still doesn’t understand why people are taking pictures of their food and putting them online—and I called him the day the war began. He hadn’t heard, and he didn’t believe me when I told him. The next day, he told me with a sigh, “Russia always has a tzar.” As of eighteen days into the war, my Papa says Putin can’t win because “every Ukrainian will shoot him from their balcony.” My father’s prophecies pour out of him because they are memories: “When the Nazis occupied Belarus, a country three times smaller than the Ukraine, they had to station 6,000 soldiers there to fight the partisans. The same will happen in Ukraine. They will lose, lose, lose, until they grab a piece of something and call it a victory.”

And what about the nuclear bomb? “He’s bluffing,” Papa says. All he has to do is push a button, I counter, and Papa corrects me, “Putin pushes a button, and then a general pushes a button, and then a government official pushes a button, and then a deputy pushes a button, and then a supervisor pushes a button, and then a lieutenant pushes a button.” And you hope that, somewhere along the chain…? “Yes, maybe some person will understand that with this button he kills himself and all humanity.” He clears his throat and continues: “But he won’t do it. One of his daughters lives abroad.” I look it up and correct him—Maria was expelled from the Netherlands in 2014 after the Malaysian flight was shot down by Russian rebels. “Well, of course, she’s in Moscow now.”

So what does he think we should do? No one wants to do anything, he says, misquoting Churchill (in Russian, of course)… something about shame in addition to defeat when you appease an aggressor. I found it in English: “We seem to be very near the bleak choice between War and Shame. My feeling is that we shall choose Shame, and then have War thrown in a little later on even more adverse terms than at present.”

And what do I think about the conflict in Ukraine? As a “Russian” or whatever it is that I am? I think most “Russians” in America left for a reason, and I pray the “Russians” in Russia are not sacrificed by the new tzar like so many before them. I think the “evil empire” that Reagan once pointed to is alive and well. And I definitely don’t think we should be boycotting Russian-sounding things; that doesn’t feel like a very helpful or truthful thing to do. I think helping is hard and is more than a click or post away—besides, this week, the tzar shut down Instagram in Russia. And as the free press in Russia disappears (again), I am reminded of a line from a poem I read this summer:

I am all alone; all around me drowns in falsehood:

Life is not a walk across a field.

It’s Pasternak’s banned “Hamlet.” I bemoaned the English version, insisting on trying to find righter words, somehow closer to the original, in order to explain it to my husband. This poem that had made me cry suddenly became something else, unwieldy in its flatness. Translation is obviously always an atrocious act of loss. Perhaps some misconstrued phrase outweighs the casualties of communication. But perhaps I should be grateful that there are things I will never understand. That God or luck may protect me, and I may never know what it means to pray with my hands together in St. Andrew’s Church in Kyiv or to collect onions from a bombed warehouse in Mykolaiv or to speak only in the language of trauma. And that I will somehow learn, instead, to help those who knew the battlefield go on to know the softer pains of cultural barriers, the gentler wounds of mistranslations.

Liba Vaynberg is a playwright and actor based in the Bronx. She speaks Russian, so that’s not why her parents still don’t understand what she does.