“She Drew Obsessively”— Ilka Gedő’s Legacy, Restored

Every good curator knows that an important artist’s centenary must not be overlooked. But in Hungary, after an entire century of not only overlooking so many of their great artists, but oppressing and blacklisting them, sometimes sending them to labor camps and concentration camps, today there is a more complex dimension to many of these centenaries.

Her pencil and sketch pad were both a way of understanding the world and protection against its cruelties.

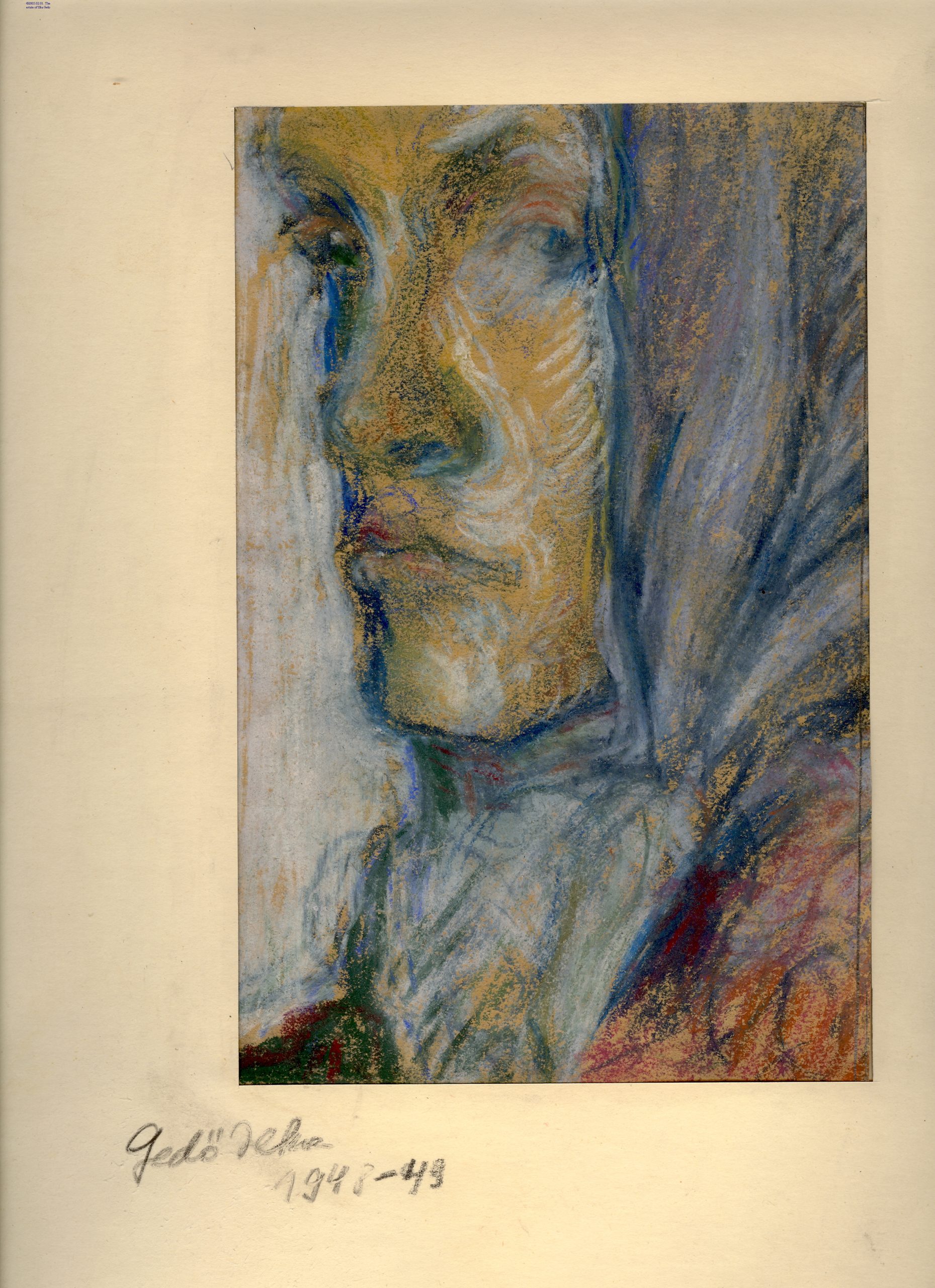

Self-portrait with a Hat by Ilka Gedő. 1983. Private collection. Courtesy of The Estate of Ilka Gedő, Budapest ©.

What is being played out here, albeit somewhat obliquely, is the righting of historical wrongs. In the case of Ilka Gedő (pronounced Ged-euh), born a woman and Jewish in an era of murderous antisemitism, where opportunities for women were severely curtailed— her art had little chance of acceptance. On top of that, Gedő’s artistic sensibilities were idiosyncratic. She did not fit into the dominant art historical narratives of her day. She was cast out from both the official and unofficial cultural circles—by the Communists for not making art in the mandated socialist realist style, and by her modernist peers for persisting with figuration. Going it alone was the only option for Ilka Gedő, and that was what she did.

From the age of 11, Ilka Gedő drew obsessively. Her pencil and sketch pad were both a way of understanding the world and protection against its cruelties. As an only child-driven on by her ambitious mother, Gedő’s drawings slowly matured from naturalistic studies of the middle-class, Budapest Jewish world from which she came, to more introspective subject matters, especially self-portraits.

In the sensitivity of her lines—ghostly, fragile as glass—the shockingly tenuous position of European Jewry can be glimpsed.

In 1938, a year before she graduated high school, widespread anti-Jewish laws were introduced in Hungary. Gedő’s plans to study art in Paris were scuppered. She did not enroll in the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest but instead chose to continue her studies in the small, private schools of the capital run by artist teachers. For the next four years, until she and her family were forced into the ghetto, Gedő would study with three different artists, all of whom were Jewish, none of whom would survive the war. That all three of her mentors were murdered would have a significant impact on Gedő, leaving her not only isolated but without any champions in the world of art.

On March 19, 1944, Hungary was occupied by the Nazis. A 1941 census put the Jewish population at 825,000. In a little over a year, close to 600,000 Jews were decimated. The Gedő family were confined to the Ghetto, and only narrowly escaped deportation. During those terrifying months, Gedő continued to draw obsessively. In the sensitivity of her lines —ghostly, fragile as glass—the shockingly tenuous position of European Jewry can be glimpsed. Her Ghetto Drawings live on today as important historical documents in museums the world over.

From left to right: Self-Portrait in the Ghetto, Portrait of a Girl with a Bow and Boy with Yellow Star. By Ilka Gedő. 1944. Budapest Ghetto. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem and the Estate of Ilka Gedő, Budapest.

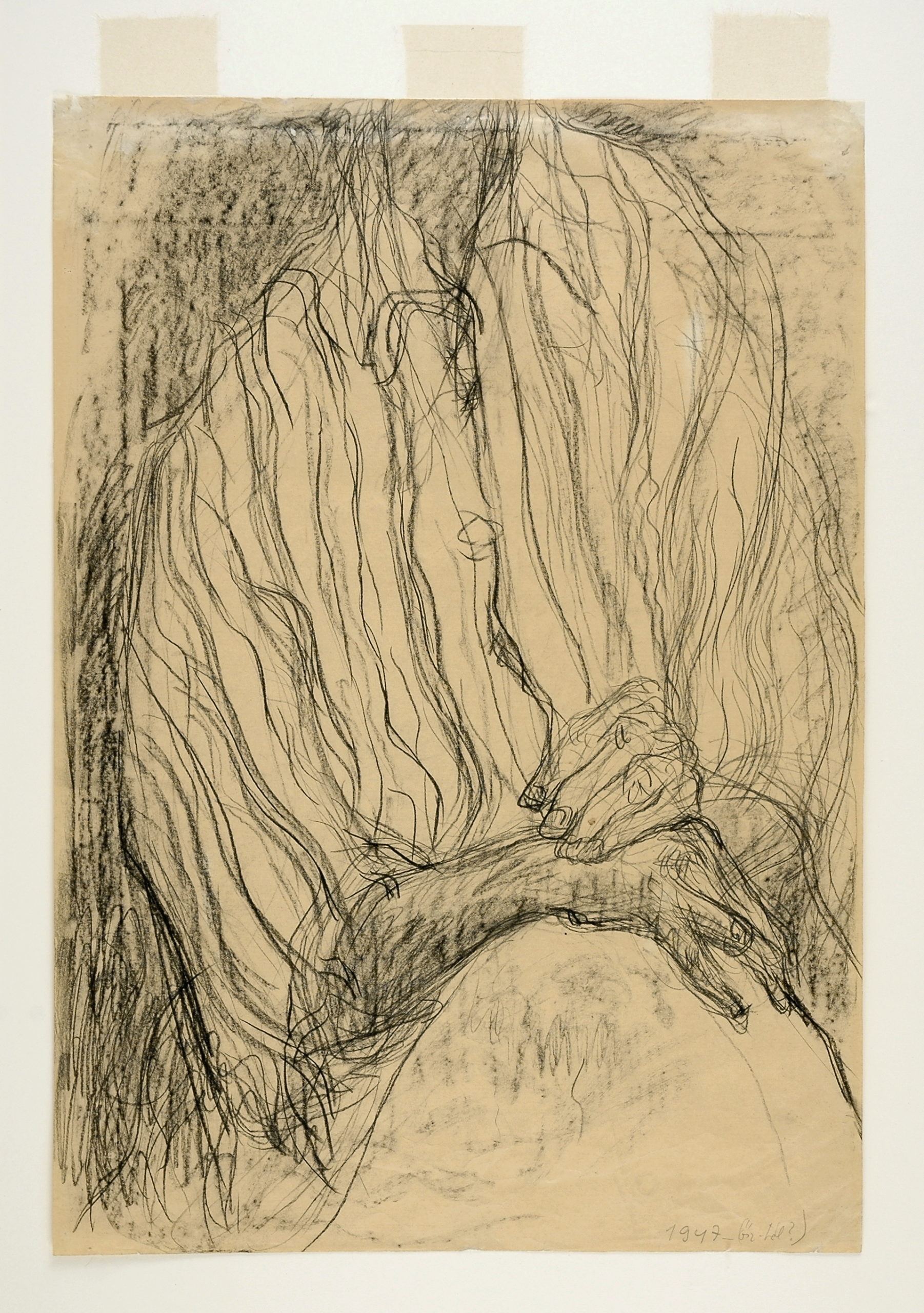

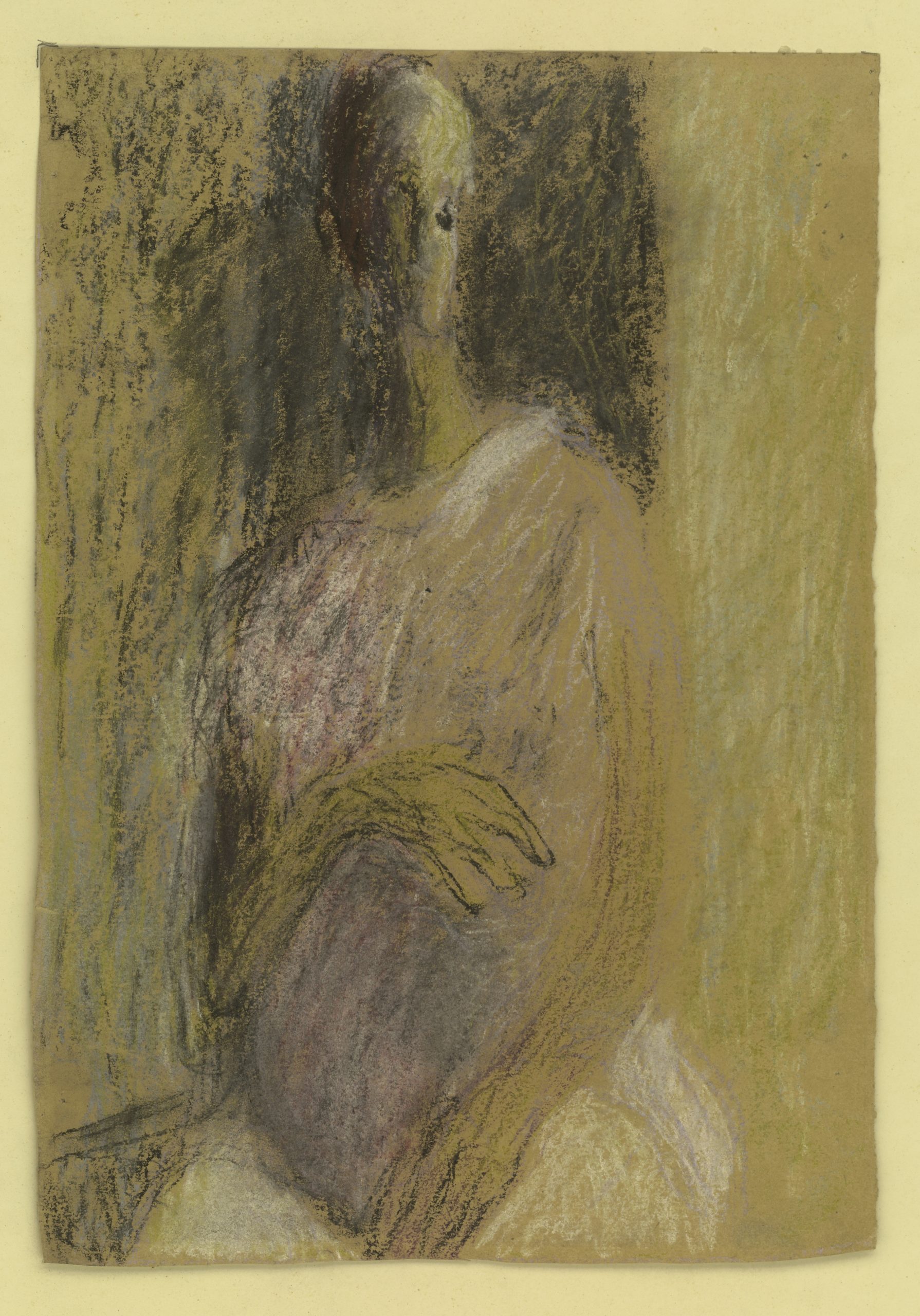

The post-war years—assuming the war actually ends for those that lived through it —were a time of turmoil and productivity for Gedő. The years 1945-1949 are now regarded as her artistic zenith, and the drawings from that era make up the majority of her centennial exhibition. It was a time when her self-portraits became liberated from the constraints of realism.

When a new level of psychological depth and dramatic tension were achieved, not through her facial depictions, which were increasingly erased, but through her lines: long, loose, febrile, trembling, exquisitely sensitive lines. Stylistically reminiscent of Alberto Giacometti – whose work she would only come to know decades later – these drawings often eschewed traditional notions of portraiture. In some, Gedő experimented with role play by disguising herself in hats and scarves, obscuring her gender and age. In others, she is by turns determined, feminine, pensive, headless, pregnant and nakedly traumatized. Her hands are especially expressive. Note the tension in her fingers. In her pregnant self-portraits of 1947, the absence/erasure of her face implies an ambivalence towards becoming a mother. Her diary entries from this time attest to her struggle to reconcile motherhood with being an artist. Two years later Gedő would plunge into radical silence, ceasing all artistic activity for 16 years.

The hardest aspect of discovering Gedő’s work is understanding those 16 years. To me, her choice, and all of the attendant grief it surely came with, was akin to self-harm. Long, lonely, sustained self-harm. When I don’t write I feel unmoored, shapeless, dead on the inside. So, why did she do it? In order to raise her family? Not quite. Trauma from the war? Perhaps in part. Artistically lost? Now we’re getting warm.

In post-war Hungary, the choices for an artist were pretty stark. Make art that glorifies Communism and the Party, or become invisible. Gedő chose the latter, as many other non-conformist artists did. There was however one other choice, and that was to become part of the small, but rich circles of underground artists and intellectuals, a world to which she was connected through her husband Endre Biró, the famous biochemist, who was involved with the underground intellectuals. But Gedő felt strongly that she didn’t belong there either, and although it was never formally stated, perhaps the feeling was mutual? In the simplest of terms, the post-war Budapest underground art world was mostly comprised of abstract artists and surrealists. Gedő was neither.

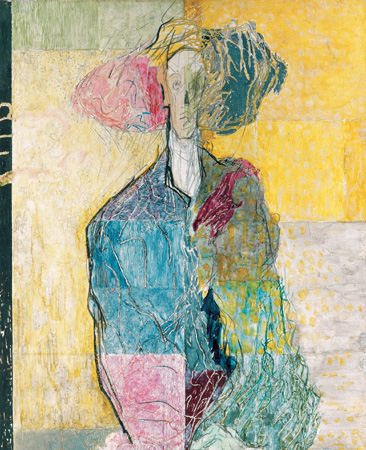

Her art was predominantly figurative, and in its late-life reincarnation, it was most closely associated with expressionism, with intense color poetry and highly technical brushwork. Even then she never entirely abandoned figuration. She saw no need for it. She was not interested in abstraction.

Here’s Kafka from a 1921 diary entry (referenced in “The Art of Ilka Gedő”, István Hajdu & Dávid Biró, Gondolat Publishers, Budapest, 2003):

“The inescapable obligation of self-observation. If I am observed by someone else, I must of course observe myself. If I am not observed by someone else, then I must observe myself even more thoroughly.”

Throughout her life, Gedő obsessively documented herself, whether through self-portraits, diary entries or the painstakingly recorded process of creating her expressionist paintings. I observe myself so that I don’t disappear. I am not invisible if I observe myself. The act of self-observation is part of my process. I observe myself therefore I am.

All of these were true of Gedő’s life and art, which entailed a kind of existential battle against erasure: as a woman; as a Jew; as a non-conformist, female, Jewish artist living in Hungary during the Communist era; as an artist whose sensibilities placed her outside of the dominant art movements of her day. Gedő’s silence, when seen through the lens of self-observation, becomes less about raw bone survival and more about reaching for the eternal. Through portraits, the timeless thumbprint of our humanity; and through color, the transcendental poetry that has always existed beyond language.

In 1965, after a small, unofficial studio show of her post-war/pre-silence drawings, Ilka Gedő began to paint again. Beyond the walls of her studio, a slow cultural thaw had begun. Though the hopes of the 1956 anti-Soviet uprising had been dashed, in its place there emerged an uneasy compromise. Many of the (male) blacklisted artists of the 1950s were gradually beginning to gain official recognition. Meanwhile, the intensive color studies undertaken by Gedő during her silence began to bloom into glorious expressionistic works, where stylized portraits, gardens and mysterious, otherworldly figures abounded.

I am not invisible if I observe myself. The act of self-observation is part of my process.

Double Self-portrait by Ilka Gedő. 1985. Private collection. Courtesy of The Estate of Ilka Gedő, Budapest ©.

In 1980, Gedő’s first large-scale museum exhibition took place in regional Hungary. At the age of 59, she had “officially” arrived. Two years later she had her first museum show in her hometown Budapest. Three years after that she would die from cancer. The story of Gedő’s late-life, short-lived success would be echoed across her generation, with so many other pioneering female (Jewish) artists being overlooked until the very end of their lives. In 1902 Paul Klee (one of Gedő’s heroes) wrote: “I want to be as though new-born, knowing nothing, absolutely nothing, about Europe; ignoring poets and fashions…”

It took Ilka Gedő 16 years to lose herself from the stultifying yoke of fate, to carve out her artistic path and connect with the eternal. Grit like that is always worth celebrating.

Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest presents “Half Picture, Half Veil” Works on Paper by Ilka Gedő (1921-1985) Centenary Exhibition from May 26 – September 26, 2021.

In 2021, Nicole Waldner‘s work is forthcoming in the Calvert Journal and Agenda Poetry. Find her on Instagram: @nwaldnerauthor