Jane Lazarre on How This Age of Crisis Affects Our Inner Worlds

Writer Jane Lazarre is no stranger to the pages of Lilith; an excerpt from her provocative and resonant novel, Inheritance, appeared in the Summer 2009 issue, and her memoirs The Communist and the Communist’s Daughter and The Mother Knot were both the subjects of previous conversations with Lilith’s editors.

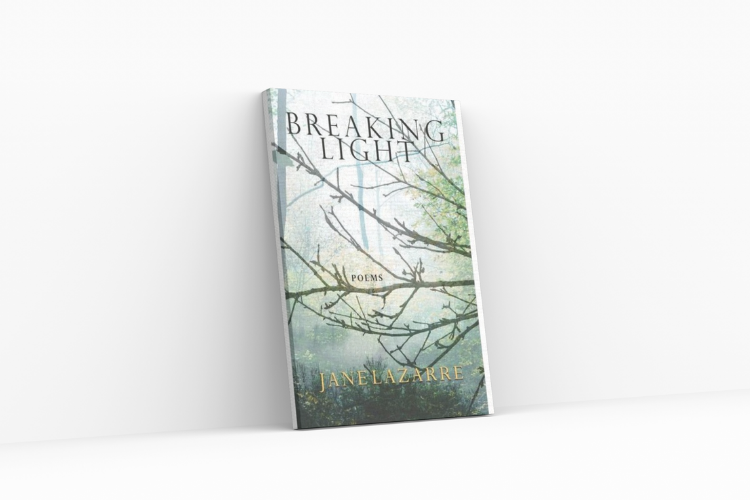

Now Lazarre (author of ten previous books and creator of the undergraduate writing program at Eugene Lang College at the New School) is back, this time with a collection of poetry—her first—entitled Breaking Light (Hamilton Stone Editions, $16.95) and she once again talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about some of her recurring themes and the role of the poet in the world today.

YZM: You’ve published novels, essays and a memoir and now, a first collection of poems; have you always written poetry or is this a new form for you?

JL: Writing and studying poetry is not a new form for me, but it is a new and first time publishing. I began a serious study of American poetry, its forms, varieties and history, about 15 years ago. A very close friend of mine died and I wanted to write about him. Poetry seemed the best way to reach and express my feelings. The poem, “Schubert Sinking In,” was written for him in my early years of study, then revised over the years. At the same time one of my long time private students wanted to write and study poetry. I have always been very aware of the rhythms, sounds and images of language in my prose, so it was not a great leap, though there was much to learn. The study, and reading so much poetry, eventually also from poets in other languages (translated,) intrigued and enlightened me further. Most recently, I have been studying the history of African American poetry as African American prose has influenced me in many ways – in my own work and in my teaching. I have been reading and learning most recently from Rita Dove and Natasha Trethewey.

YZM: Let’s talk about the book’s title—what it means, why you chose it.

JL: The title, Breaking Light, echoes specifically the poem, “Chiaroscuro” — morning light breaking in November, the month when I was born. But many of the poems include images, or are centered on images of darkness and light, the dark of our lives when illness or tragedy comes, the light that breaks through when we or loved ones or even the world itself manages to survive tragedy and horror. Morning light and the darkness of the past year of COVID-19 infuses the first poem, “Virus Time, A Woman’s Lament,” as it does in the poem, “Birth” – “a tender, calming darkening light.” The play of, emotional meanings of, and memories of color infuse many of the poems — for, as the writer and scholar Miryam Sivan writes in the Introduction, “. . . color is wavlengths of light.”

YZM: Many of the poems are about the loss of your mother.

JL: When the COVID-19 virus shut down New York City in March of 2020, locking us in and distancing us from those we love, I felt that for many people, including myself, time frames started collapsing, as they might in a generational novel. I was suffused with memories of my mother, love and anger, loss and guilt spread through me as these emotions had not in many years.

My mother died when I was seven after a long and traumatic illness of cancer, at a time when treatment for cancer was very limited. She has always been in my mind. I grew up with many idealized and false stories about her, silences and lies, so when I began to write seriously, in my early twenties, she was the first haunting I needed to translate into words. She is in all my books in one way or another, from the fiction of Some Place Quite Unknown, which uses her actual letters from a trip to Europe she took in my early childhood, to the various motherless daughters in my novel, Inheritance.

Remembering her is central to my writing: my memoir, Wet Earth and Dreams, the story of my own first bout with cancer and the beginning of a deep psychoanalysis, as well as in my fiction close to my actual life—what is now called “autofiction”.

So I was shocked that at the age of 77, the old traumas still had such force, though I now understand this has been true for many during the pandemic. The old stories don’t simply close up within—they are resolved and unresolved again, buried and then suddenly forceful enough to knock you down.

As I wrote in one poem, “I am amazed by the longevity of longing.” So when I began to choose poems for the collection of Breaking Light, I chose many poems about my mother, worked on them again, revising and refining, seeking to re/member the past in a way to help cope with the present—centering for me as for many others on loss and fear, being separated for a year and a half from one son and a granddaughter, unable to touch or embrace my other son who lives near by. Motherhood and daughterhood are obviously intertwined for women, and for a motherless daughter the two central identities can merge. For me, writing and rewriting is the door and path back to the present moment of clarity, even of sanity.

YZM: Another recurring theme is water; was this a conscious choice?

JL: Water is a constant moving image for me—as it is for many. The ocean is a symbol of the mysteries of memory, a mystical presence in my work and in my dreams, figuring in many of my novels as a source of knowledge, peace but also loss. I love to swim, especially in a certain place in Truro, Massachusetts, where the Pamet River meets Corn Hill Bay – the rhythm of it, the breathing and holding of breath, the effort for graceful movement of limbs and back, the way when you lie still the water can hold you. Water also evokes my mother to me — she taught me to swim, and I have memories of her near water as I wrote in “Arm Over Arm.” The last poem, to my granddaughter when she was a child, combines the waters of the present with memories of my mother — on the Queen Mary, crossing the ocean to Paris. I dont use water imagery in a conscious way, it is just always with me in my unconscious and in my imagination. When I am actually near the ocean, as I was recently, I feel a sense of openness and inexplicable peace. I believe this transference, as I might call it, to ocean, rushing rivers, calm bays and lakes, is common if not nearly universal.

YZM: The first poem, Virus Time, deals with the pandemic. Do you you feel poets have a responsibility to address global issues; why or why not?

JL: I would never want to say what writers in general ought to do. I love some poets and poems that speak only to the internal, personal world. For myself, along with many other writers as we know, I could not publish a book in any genre without referring to and describing the shared trauma of the pandemic we have been through and are still going through. I have deep rage at the autocracies around the world, especially here in this country, whose mendacious policies allowed the pandemic to grow and kill so many, especially the poor, and especially people of color. The so called outside world has invaded deeply and permanently the inside world, even for some of the most privileged. As a white, Jewish mother of Black sons, having been married to a Black man for over 50 years, having been a student of Black American literature, and growing up as a child of American communists, it was not new to me to believe in my responsibility to respond to issues of justice and deprivation, the passion for freedom and prevalence of cruelty—it was more or less built into my cells.

Now, in this time, as we all struggle to understand the ongoing pandemic and the threat of fascism in this country, I am interested in writing that addresses the pressing questions of our time, ways to write during what Nadine Gordimer, during the apartheid years in South Africa, called “the interegnum.” It is not only in the first poem, but in many of the poems, where events in the “outside” world become “inside.” The experience of radiation for cancer just when a tsunami was devastating Japan with its awful history of radiation poisoning. The mass migrations of the homeless all over the globe—the meaning of home and homelessness. American racism which, after the murder of George Floyd and the rise of Black Lives Matter, was suddenly visible to many in white America, clashing with their privileged lives. For me, it is impossible to evade or ignore these realities in my work.

I am now involved in a work (novel or memoir or both?) about my relationship with my African American mother-in-law, who at 97 lives in a nursing home. We are both motherless daughters. We have loved each other, helped each other, fought and made up and talked endless talk for over fifty years. There is no way to have lived the life I have lived and to separate “politics” from “art.” “People are trapped in history,” as the great James Baldwin wrote, “and history is trapped in them.”