Feminists in Focus: A Peaceful Middle East

Welcome to the latest installment of “Feminists in Focus: Film News and Reviews,” an incisive look at the new film, Budrus, from filmmaker and Lilith contributor Elizabeth Mandel. Enjoy!

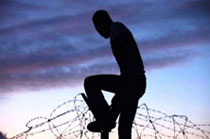

The media is replete with violent images of Palestinians, Israelis and Muslims; of veiled Muslim women subjected to the will of the men in their lives; of a sense of hopelessness regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The recent documentary film “Budrus,” directed by Julia Bacha, offers an alternative version to this story, and through that, hope for an alternative vision for the future. The film chronicles the events that unfolded in Budrus, a tiny (pop. 1500) Palestinian village on the West Bank, as the residents came together in nonviolent resistance against Israel’s separation barrier cutting through the village, its cemetery and its life-sustaining olive groves.

The media is replete with violent images of Palestinians, Israelis and Muslims; of veiled Muslim women subjected to the will of the men in their lives; of a sense of hopelessness regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The recent documentary film “Budrus,” directed by Julia Bacha, offers an alternative version to this story, and through that, hope for an alternative vision for the future. The film chronicles the events that unfolded in Budrus, a tiny (pop. 1500) Palestinian village on the West Bank, as the residents came together in nonviolent resistance against Israel’s separation barrier cutting through the village, its cemetery and its life-sustaining olive groves.

In 2004, the construction of the barrier came to Budrus. It was scheduled to cut through the town, ostensibly unavoidably, for security reasons (no concrete reason is given for why the barrier takes a circuitous path that cuts through and isolates villages from their land and each other). In response, Ayed Morrar, a lifelong activist and six-year-veteran of Israeli prison, organizes “the Popular Committee Against the Wall,” a non-violent resistance movement designed to stop the progress of the barrier. At first it seems the protests are almost benignly endured by the Israeli military police assigned to Budrus. There is internal disagreement about whether the bulldozers should stop or continue. But soon, olive trees are being dug up, and it seems inevitable the protestors will be stopped and the barrier erected.

In 2004, the construction of the barrier came to Budrus. It was scheduled to cut through the town, ostensibly unavoidably, for security reasons (no concrete reason is given for why the barrier takes a circuitous path that cuts through and isolates villages from their land and each other). In response, Ayed Morrar, a lifelong activist and six-year-veteran of Israeli prison, organizes “the Popular Committee Against the Wall,” a non-violent resistance movement designed to stop the progress of the barrier. At first it seems the protests are almost benignly endured by the Israeli military police assigned to Budrus. There is internal disagreement about whether the bulldozers should stop or continue. But soon, olive trees are being dug up, and it seems inevitable the protestors will be stopped and the barrier erected.

Enter Iltezam, Morrar’s fifteen-year-old daughter. Iltezam challenges her father to include the entire community in these community protests, and soon she and the other women of the village are on the front lines. Iltezam herself jumps in front of a bulldozer, and the women rally round her. Like so many other protest movements lead by women, such as the Argentine Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (also known as Mothers of the Disappeared), their participation confounds the authorities. Because they challenge not only the authorities, but also expectations and familiar rules of the game, their actions are tolerated beyond what would have been deemed acceptable had they been men.

While the military men are caught off guard, it is the squad commander, a woman, who is the most deeply confused. She has a job to do, and she clearly believes in her mission. It is a job best done when one can maintain a sense of apartness and otherness. From the beginning, though, the villagers find a way to break down her separateness. Her name, Yasmine, is a popular Arab name, and the male villagers tauntingly invite her to come join “her own.” It is clear that they, too, behave differently with a woman than they would with a man. When the women join the resistance, Yasmine seems torn between resentment and surprise coupled with deep respect. She resents the complication, but respects their utter lack of fear in standing up for what they believe in. While she doesn’t say it, one gets the sense she has never seen girls and women participating like this before on similar missions. One wonders if these were diplomatic negotiations rather than grass-roots protests what kind of dialogue would ensue between Yasmine and Iltezam. While Yasmine never comes around to seeing (or at least admitting to seeing) the point of view of the residents of Budrus, something in her is surely shaken, and her assumptions are re-examined.

So too are the assumptions of the villagers about Israelis, when a group of Israelis come to join the protests. The act serves several functions, including a standing-down of the military police, a legitimization from a new quarter, and the building of grassroots relationships, which may lead someday to deeper cooperation.

In addition to presenting powerful women and positive Israeli-Palestinian relationships, the film briefly but importantly addresses the under-discussed issue of age in escalation. At one point, non-violence turns to rock-throwing by young Palestinians, which is answered with live fire by the young Israeli military police. A senior member of the Israeli military reminds us of the explosive combination of stress, weapons and youth, and one is left wondering how different the current situation would be if near-children weren’t making daily life-and-death decisions.

“Budrus” re-raises the as-yet-untestable theory that the world would be a more peaceful place if more women were leaders, playing on their own terms, rather than conforming to the patriarchal power systems. It offers hope and alternative solutions beyond the movie screen, as its outreach campaign brings the film to the West Bank. One can only hope that the brave women and men, Palestinian and Israeli, of “Budrus” can inspire a new approach to peace and cooperation in the Middle East. Clearly the current models are not working.

For upcoming screenings of “Budrus”, click here.

For more information about the film, click here.

–Elizabeth Mandel

Elizabeth Mandel is a documentary filmmaker with a special interest in women’s empowerment and gender-based violence. She co-directed the 2010 documentary “Pushing the Elephant,” about a Congolese mother and daughter.