Mama Lives On

My daughters, born and raised in Israel, are fully bilingual, but they are steeped in Israeli culture. They had heard of Santa Claus—whom little Charlie, the younger brother in the novels, mistakes for the boogey-man—but they had not heard of the boogey-man. “What’s so special about the Fourth of July?” they asked when, in one novel, Papa’s best friend arrived with firecrackers and took the children out at night.

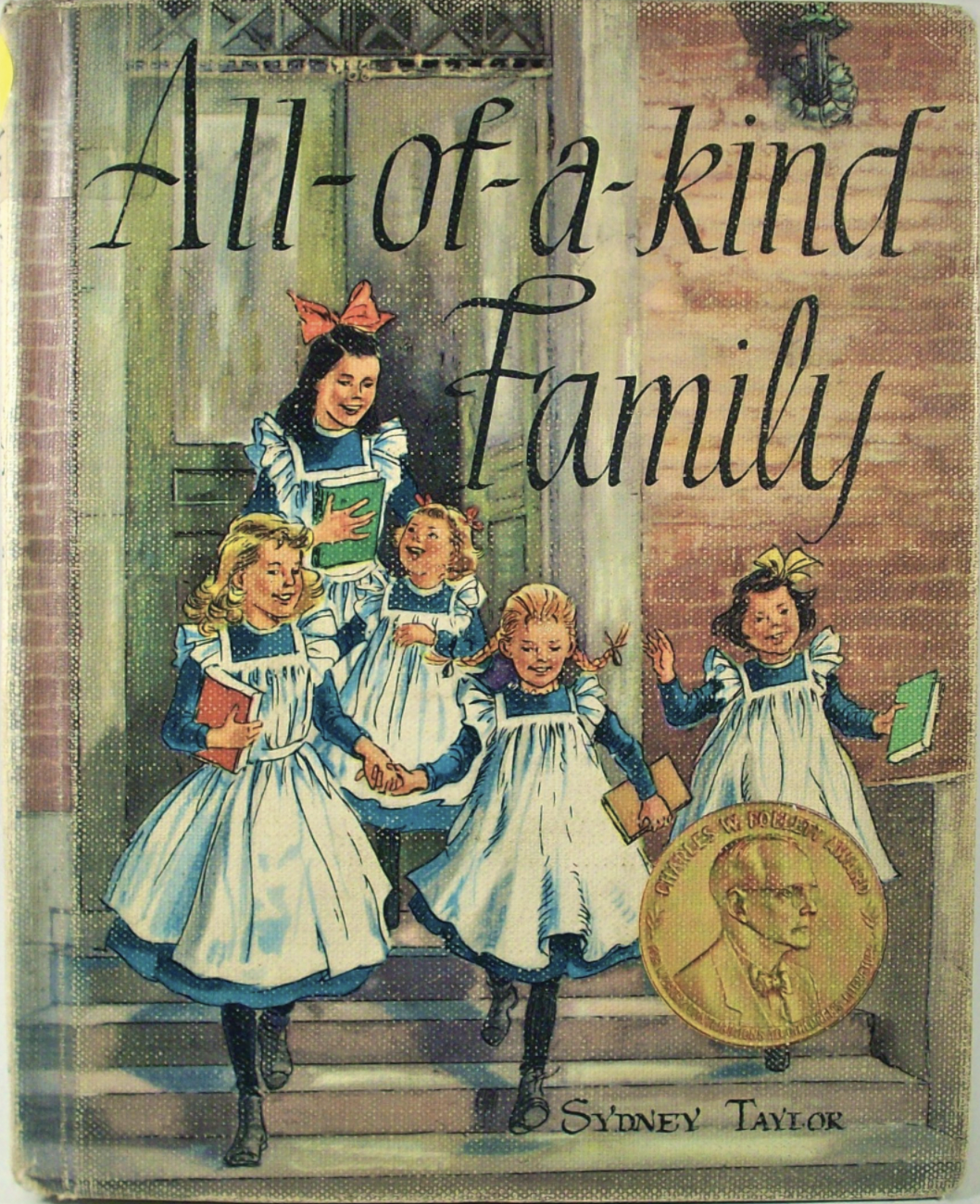

American Independence Day was foreign to them, but the Pesach seder and Purim play were not. I realized the irony of trying to translate the unfamiliar aspects of American culture to my Jewish children, given that Sydney Taylor wrote the All-of-a-Kind Family books in part to normalize Jewish culture for American children. As June Cummins notes in From Sarah to Sydney (Yale, $35.00), her biography of Sydney Taylor, “It was impossible to find books about Jewish children at bookstores or public libraries before All-of-a-Kind-Family,” published between 1951 and 1978 as a series of five books for young readers.

Cummins hails Taylor as a “pioneer in ethnic literature for children,” which came as a surprise to me. By the time I became an independent reader in the late 1980s, there were plenty of Jewish heroines in the chapter books I found in my local public library—from Marilyn Sachs’ depiction of two sisters growing up in a poor family in the Bronx in the 1940s to Joanna Hurwitz’s portrayal of rabbi’s daughters like myself. Still, it was the All-of-a-Kind Family books that I read again and again and again, until the black-and-white illustrations became seared in my memory like images from a family photo album. I was convinced that I too had waited in line with Sarah to con- fess to the library lady about a lost book, eaten broken crackers and penny candy illicitly in bed with Charlotte and Gertie, and spied on Ella as she tried to have a private conversation in the parlor with her boyfriend Jules. Surely these stories, so vivid in my memory, had to be true.

For fans of the All-of-Kind-Family series like myself, the fascination of reading Cummins’ biography of Sydney Taylor lies in the discovery of what is, and is not, autobiographical. Many readers know that Taylor’s fictional family is based on her own experiences growing up on the Lower East Side and in the Bronx in the early decades of the twentieth century; but I, for one, had no idea that Sarah was also the middle of five sisters, all of whom had the same names as their fictional counterparts; they were followed by two younger brothers. Sydney was born as Sarah Brenner, distinguished from her older sisters Ella and Henny and her younger sisters Charlotte and Gertie by her studiousness and her literary talent—she kept a journal, which she called a “thought book,” and her childhood memories became the basis for her bestselling novels which went on to delight generations of readers, Jewish and non- Jewish alike.

Taylor and her siblings were born to an Eastern European Jewish father named Morris Brenner, who shed his sidelocks and religious clothing when he arrived in the German city of Bremen and married a well-off young woman who, at one point in their courtship, traveled all the way to America just to play hard-to- get. Morris and Cilly Brenner established a junk business in Bremen, but persecution from local bureaucrats drove them to immigrate to America in 1901 after the birth of their oldest daughter, Ella. Morris opened another junk business on the Lower East Side, trading in recyclables like Papa in All-of-a-Kind Family. Indeed, as Cummins insightfully remarks, Taylor also worked in the junk business, recycling the scraps of her family history into the pages of the books she wrote.

Cummins, a professor of English and comparative literature who died tragically of a degenerative neuromuscular disease three years before her biography was >published, devoted much of her schol- arly career to excavating Taylor’s life and legacy. She drew her source material from Taylor’s journals and correspondence, from a memoir published by Taylor’s sister Charlotte, from family history recordings by Ella and Charlotte, and from interviews with Taylor’s younger brothers, nieces, and daughter.

Cummins demonstrates that for all that Morris resembled the kind, jocular fictional Papa, Cilly was a far cry from the serene, sensible fictional Mama, a bedrock of stability who always knew just what to do and say. Cilly, depressed and dissatisfied, never really felt comfortable in America and longed to return to the financial comforts she had enjoyed in Germany. Ella later recalled her mother’s attempts to induce miscarriage when pregnant with Gertie by jumping on and off tables and washtubs, to no avail. Cilly tried to commit suicide twice, first by put- ting her mouth to a gas pipe after a bout with pneumonia, and then again after the death of her toddler son Ralph, who cut his finger on a piece of glass and was medically mistreated with too much chloroform. Cummins notes that while these tragedies are not included in Taylor’s novels, the five sisters’ younger brother, Charlie, survives a life-threatening accident, and Mama seems ambivalent about sharing the news of her last pregnancy— “another mouth to feed”—with her daughters. She thus shows how Sydney “recycled” the material of her childhood into a more sanguine, less haunting tale.

Cummins considers various aspects of the Brenner girls’ childhoods that are reflected in Taylor’s novels, including the centrality of public school and the public library in a household where books were an unaffordable luxury. Sarah once explained, in a letter to her sister, that she preferred her own books to “public books” because she has “no right” to mark up library books, and because she feels delight in owning something she loves. Sarah, who changed her name to Sydney as a teenager, enjoyed school as much as her fictional counterpart, but she had to drop out after two years of high school to work, finding employment first at an embroidery company and then as a stenographer. “College? A girl go to college?” Charlotte recalled her father asking angrily when Sarah expressed interest in continuing her schooling. “There you go getting American ideas.” Though Sarah never returned to high school, she remained an avid reader, and libraries played a very important role in her career—on account of her positive portrayal of libraries in her novels, she was lionized by the American Library Association and frequently invited to speak about her books at public libraries nationwide.

Taylor became a published author much later in life, almost by happen- stance. She and her sisters spent their summers working together at the Cejwin Camp in upstate New York, where Taylor wrote countless plays about biblical stories, Jewish legends, Jewish holiday observance, and the modern State of Israel, entwining American history and Jewish culture. One summer, Taylor asked her husband to dig out a script she wanted to use at camp, and he discovered several family stories she had penned. Ralph, who had recently noticed an announcement for a children’s literature prize, had his secretary type up the stories and submitted them on Taylor’s behalf. Taylor was astonished to win a handsome monetary prize as well as a publishing contract. She immediately picked up the phone to call her mother, declaring, “Mama, you’re going to live forever.”

Mama, Papa, and their children lived forever, but as Cummins chronicles, it was not always easy for Taylor to publish their stories. She had originally begun writing down her childhood memories to share with her own daughter and only child, Jo, born when Taylor was 31. But after her book was awarded a publishing contract, she found herself often at odds with her editor, Esther Meeks, who pushed Taylor to Americanize her characters and downplay their Judaism. Though the first book was met with commercial and critical success, Meeks rejected the manuscript for Taylor’s second book, All- of-a-Kind Family Downtown—about the sisters’ involvement in the local settlement house—on the grounds that it dealt with issues too gritty and stark for young children; Downtown was not published until 1972, as the fourth book in the series. In spite of her literary successes, Taylor remained ambivalent about her craft: “Sometimes I wish I could throw my typewriter out of the window,” she wrote. “At other times I could kiss it for the happiness it has brought me.”

My twin daughters are now eight, the age of middle sister Sarah in the first All-of-a-Kind Family book. It has been two years since I read the entire series out loud to them, and they’re each reading it on their own, re-encountering the library lady and the penny candy man now that they are old enough to walk to the library by themselves, old enough to buy their own candy, and old enough—I hope—to know better than to eat it in bed.

Ilana Kurshan is a frequent Lilith contributor and the author of the award-winning memoir If All the Seas Were Ink.