Being Chana

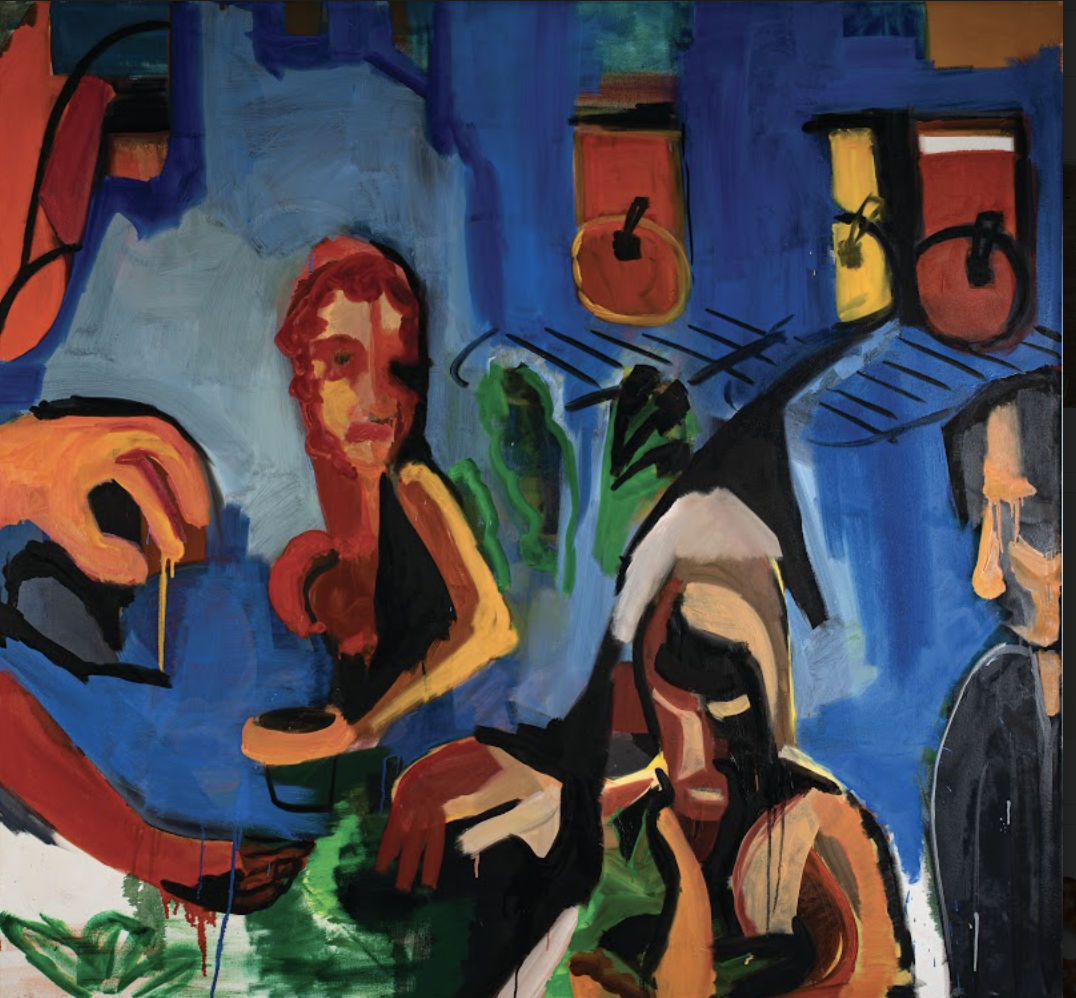

SARA BENNINGA, LOOK, OIL ON CANVAS, 2019, 62X59 INCHES (PHOTO BY: SHAI HALEVI).

My friend and I were celebrating at a restaurant-slash-bar one Saturday night when my psalmic cup got knocked over. Here’s what happened: A server offered us refills. My friend ordered another glass of wine. I said I needed some time to think. When the server returned, I said I’d like a glass of the same wine. The server gave me a look, hesitated, glanced at my friend, and implied that I was too drunk to keep drinking.

I was not drunk. I’d had an old fashioned, so I wasn’t sober, but I wasn’t drunk. “That was very rude,” I told the server, thinking my words would clear things up. But no, she stood her ground and informed us that she had the authority to cut people off. I started to cry. “I’m not drunk!” I said, perhaps making a good impression of a drunk person.

“No, it’s because of how you talk,” my friend said in an attempt to console me. “We all speak differently.” This didn’t comfort me at all.

On the one hand, I know what my friend meant. How I talk is mostly out of one side of my mouth while the other half of my face stays still. My voice is slightly nasal, according to my neurosurgeon’s office notes, and my Rs are not crisp, according to me. This is the tip of the iceberg that is my disability.

Then again I’m not entirely sure if that is what my friend was referring to. People have told me that my speech patterns are unusual. I pause a lot. That’s also “how I talk.” And I don’t think any of this makes me seem drunk. So while I know my voice is unusual, on another level, I don’t know what the server noticed. How DO I talk? What might this person have seen? It’s painful to consider because whatever it is, whatever’s so obviously wrong with me to a stranger, is just the way I am.

How I am is also Jewish. While my voice has been with me my whole life, my Jewishness is new. I completed my conversion to Judaism this fall. I converted out of a wish to join a community, a fascination with the linguistic aspects of Judaism and Yiddishkeit (the Jewish way of life), and a need, during the first year of the pandemic, for a deeper source of strength and hope. A source of resilience that, unlike my mom or my therapist, was not another person.

As part of my conversion, I took the Hebrew name Chana. I had debated between Ruth, the name of a Biblical convert with a beautiful story, and Chana, a candidate because it was similar to the name of the babysitter who helped raise me. I named myself Chana to honor this babysitter, who is like a grandmother to me. Once I decided to “be Chana,” as I referred to it, I wasn’t going to do anything that might change my mind— like read Chana’s story in the Bible. She couldn’t have done anything so horrible, I thought. Lots of people are named that. (By “lots of people” I suppose I meant journalist Chana Joffe-Walt.) Hannah, Chana’s English equivalent, is not an unusual name, at any rate, nor does it have any particular connotation. It’s not like I’d decided to call myself Haman.

What happened at the restaurant had nothing to do with my Jewishness, or so I thought. But when I told a friend from my synagogue about it, she commented that it was sort of like what had happened to Chana in the Book of Samuel.

Chana wanted to have a baby. Her husband’s other wife had had a child by him, but not Chana.

So she went to the temple to pray for a child. The priest, Eli, saw her praying and weeping and thought she was drunk. He reprimanded her. But after she explained herself, Eli blessed her, saying that he hoped God would give her what she’d asked for, and she ended up having a child, the prophet Samuel.

When I tell the story of what happened to me at the restaurant, everyone asks me some version of “Did you explain the situation?” What situation? I mentally retort. I did explain that I wasn’t drunk. Or by “situation,” do you mean my existence?

Had I wanted to explain myself, here’s what I could have said: I was born with a benign brain tumor on the right side of my brainstem. Likely because of the tumor, I was also born with hydrocephalus, mean- ing my brain was swollen with fluid that wasn’t draining the way it should. When I was a few days old, doctors installed a shunt, which drains the fluid and regulates the pressure in my brain. I also had a tracheostomy tube in my throat til I was three, which delayed my speech. Likely because of the tumor, I have some physical asymmetries. The left side of my face is more active, whereas the right side of the rest of my body is stronger. My left eye is “lazy.” I suppose some combination of the trach and the facial asymmetry could possibly explain my voice, though I don’t know, which is one reason I’d rather not get into it, especially not with a server at a restaurant.

My psychotherapist suggested that I could have taken the server aside, told her I have neurological issues, and explained that that might have been what she was noticing. I get angry at the suggestion of taking the server aside, as if there’s something shameful about what I have to tell her, or as if she deserves a private, gentle, talking-to. My therapist doesn’t think there’s anything to be ashamed of, and I know that. But I don’t think anyone, no matter how careful, could phrase the suggestion that I explain my disability to a server, a stranger, in a way that wouldn’t make me angry.

I shouldn’t have to explain, I think. I wasn’t doing anything wrong. Unless, in some people’s eyes, there’s something fundamentally wrong with me.

When I hear Chana’s story, I don’t wonder what she did to make the priest think she was drunk. I think about her wish for a child and see something beautiful in the fact that she believed in the goodness of having a child, and in herself as a mother, enough to make this request to God. Why, then, do I wonder what I was doing wrong?

I wasn’t praying for a child. I wasn’t praying at all. I was drinking and celebrating the fact that I’d converted, just the week before, and “become Chana,” so to speak. Little did I know how literally and immediately my story would come to resemble my namesake. I don’t claim there was anything holy about what I was doing at the restaurant that night, but it wasn’t terrible, either.

Chana explained herself to the priest. Then her prayers were granted. It’s easy to feel it’s because she explained herself to the priest, and Eli went from being angry to wanting the best for Chana, that God answered her prayers. But accord- ing to Jewish tradition, it wouldn’t have happened that way. Clergy are not inter- mediaries between people and God.

If I had explained myself, would I have been rewarded? Impossible to know. Perhaps I was too hurt to appreciate a reward. Even without an explanation, the restaurant staff realized they’d made some kind of mistake, offered me the glass of wine, which I declined, and took my entrée and the old fashioned off the bill.

My friend and I went across the street to a different restaurant for dessert and, yes, more wine. When we ordered, my friend did all the talking, and I let her. The next week during Zoom Torah study class, I didn’t volunteer to read aloud the way I usually do.

As my anger subsided in the week following the restaurant incident, I began to wonder whether the suggestions that I explain myself were right in a way. Whether some good might have come from my explaining that I had neurological issues and, more importantly, how the server’s reaction made me feel. The server might have learned that not everyone who seems drunk, is. She might have learned that when you single out some- one for being drunk—which has a moral stigma, which is embarrassing—because of their disability, it feels to the person as if there’s something wrong with and embarrassing about having a disability.

Being refused a second drink represented disability creeping into yet another area of my life. Not only do I face periodic brain surgeries when my shunt stops working, but I can’t even order a glass of wine? That’s a pessimistic exaggeration, but it highlights how an incident like this can make me feel.

If I wanted the server to understand my experience, I might also have told her that the previous evening, at a Shabbat get-together, a man I’d just met gestured toward his face to ask about mine. “Stroke?” he said. Granted, he’d prefaced this by seeking, and gaining, permission to ask me “a personal question,” but what happened at the restaurant was the second time that weekend when I’d been having a good time and someone chose to remind me that I was different.

Microaggressions like this are upset- ting not just in themselves but in the memories they dredge up. “Why do you talk like that?” a French child asked me one of my first days visiting the country. “Do you need a first-floor room? I notice you’re very careful when you walk,” a real-estate agent asked me. “You’re special-educated. I can tell,” said a drunk guy in a park. “You’re practically the poster-child for the organization,” said a person helping run an event, at which I’d volunteered, to benefit an organization devoted to supporting kids with disabilities.

Jewish readers may be familiar with situations like these, in which you’re made to feel “other” because of something essential about who you are. Yet knowing how it feels to be on the receiving end of that kind of treatment doesn’t magically prevent you from inflicting it on others.

I wish I could conclude by saying that, indeed, in my life as in my namesake’s story, explanations lead to blessings. The week after the restaurant incident, I called the eatery, said I’d had a difficult experience with the server, and asked if she would give me a call. I didn’t want to chew her out, I said. I hoped we’d talk and come to an understanding so that I could keep going to my local bar. I hoped that I would be able to give this story a better ending. But she didn’t call back. A few days later, I sent an email, but there was no response.

I spoke with my friends and my therapist about what happened. But a new, running debate about what was wrong with my voice, which I may well have invited by telling people what had happened at the restaurant, left me feeling vulnerable.

One person did tell me my voice was fine. On a Saturday night three weeks after my conversion, and two weeks after the restaurant incident, I had a party to celebrate my conversion. I thought it would be nice to do Havdalah. A few days before the party, I messaged a woman I knew from a neighborhood Facebook group, who had given me my Star of David pendant after I’d posted in the group that I was looking for one, to invite her to the party and ask if she knew where I could get a Havdalah candle in the neighborhood

I’d watched rabbis at my synagogue do Havdalah on Facebook Live but hadn’t actually done it myself. I’d bought the candle, printed out the prayers, and practiced singing them. I’d gathered cinnamon sticks, for spices, and a cup of wine. But when I rolled the kitchen island with all my supplies out into the living room and readied myself to hold a giant candle in one hand and light a match with the other, I was open to advice. “You don’t have to hold the candle. Someone else can do that,” the neighbor suggested. Another friend volunteered to hold the candle. I lit the candle and said the bless- ing. At the end of each, to my delight, the crowd shouted “Amen.” Toward the end of the ritual, during the blessing for the separation between Shabbat and the rest of the week and between the holy and the ordinary, you extinguish the Havdalah candle in the wine. At that point, my neighbor advised us to put some wine on a paper towel and extinguish the flame on that, rather than dipping the candle in the cup of wine.

“You made a very nice Havdalah,” she commented afterward.

I was pleased, and relieved. No matter how well or how badly I fit someone’s mental definition of Jewish, I was Jewish.

My neighbor mentioned that she worked at a school.

“I’m a speech pathologist,” she said.

Oh no.

“I wonder what you think of my voice,” I said, sure that she could describe with precise terminology what was wrong with it.

Here I was again, Chana faced with Eli, only this time, I was asking for an evaluation.

“I think your voice is fine,” my neighbor said. “I always say that if it works for you, there’s no need to change anything,” After Chana explained herself, Eli realized he’d made a mistake and gave her his approval. That was nice. At my party, a speech pathologist said my voice was fine and complimented my Havdalah. Also nice.

This anecdote was originally going to be the happy ending to my story. It was happy. But it’s not the ending I want for the story of me and Chana. Because I’m not sure we should be looking to other people for approval that way. In Chana’s story, God is the one who needs to be able to tell whether she is praying or if she’s drunk, and it seems clear that God got the message.

The God that I believe in is not exactly the God of the Bible. I think of God as a powerful set of ideas that can motivate us to seek holiness, and praying as focus- ing intensely on what we’re grateful for and what we hope for. But the Biblical injunction against idol worship still has meaning with this interpretation, because I have a tendency to idolize people and seek their approval. I bend rather easily toward power and authority. All of these are forms of idolatry. I want to reach for a source of strength and judgment that is sturdier than all that. If I seek approval, I want to seek it from God, or from myself, or from no one.

The server thought I was drunk; the speech pathologist thought my voice was okay. It’s not that those opinions don’t matter. But they should not wholly buoy or sink me. I don’t want to give them that power.

What do you do when you call out to humans and nobody answers, or people do answer but it’s not comforting? Some people pray. Some comfort themselves. Some people call their therapist. Some people write. Some people, like me, do all of the above, moving towards an answer that may never come.

This is my explanation. May it be a blessing.

Ashley P. Taylor is a writer of journalism, essays, and fiction, based in Brooklyn, NY. Read more of her work at ashleyptaylor.com.