The “Us” and “Them” of My Life.

My father stood upright on the floor of a dress factory on West 35th Street in New York City with a steam iron in his hand for thirty years. My uncles owned the factory. My father was Labor, my uncles were Capital. My father was a Socialist, my uncles were Zionists. Therefore, Labor was Socialism and Capital was Nationalism. These equations were mother’s milk to me, absorbed through flesh and bone almost before consciousness. Concomitantly, I knew also—and again, as though osmotically—who in this world were friends, who enemies, who neutrals. Friends were all those who thought like us: working-class socialists, the people whom my parents called “progressives.” All others were “them”; and “them” were either engaged enemies like my uncles or passive neutrals like some of our neighbors. Years later, the “us” and “them” of my life would become Jews and Gentiles, and still later women and men, but for all of my growing-up years “us” and “them” were socialists and non-socialists; the “politically enlightened” and the politically unenlightened; those who were “struggling for a better world” and those who, like moral slugs, moved blind and unresponsive through this vast inequity that was “our life under capitalism. Those, in short, who had class consciousness and those lumpen or bourgeois who did not.

This world of “us” was, of course, a many-layered one. I was thirteen or fourteen years old before I consciously understood the complex sociology of the progressive planet; understood that at the center of the globe stood those who were full-time organizing members of the Communist Party, at the outermost periphery stood those who were called “sympathizers,” and at various points in between stood those who held Communist Party membership cards and those who were called “fellow travelers.”

… Every one of them read the Daily Worker, the Freiheit, and the New York Times religiously each morning. Every one of them had an opinion on everything he or she read. Every one of them was forever pushing, pulling, yanking, mauling those opinions into shape within the framework of a single question. The question was: Is it good for the workers? That river of words was continually flowing toward an ocean called farshtand [understanding], within whose elusive depths lay the answer to this question.

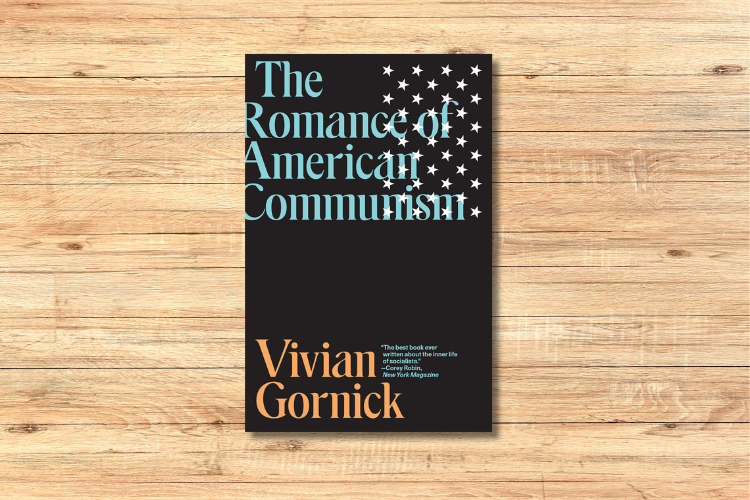

— VIVIAN GORNICK, from The Romance of American Communism