Lilith Feature

Vivian Gornick: “Writing is Feminism”

ILLUSTRATIONS BY REBECCA KATZ

This is the year— 2020—we will forever associate with the Coronavirus pandemic, but for the author Vivian Gornick it has been pretty damn good. Long an influential voice among serious readers, in these last months her name and her work have been popping up all over.

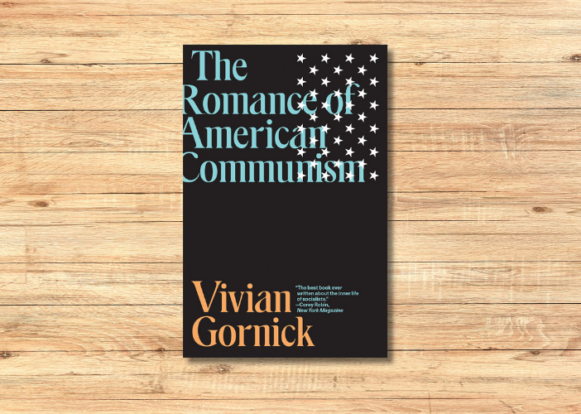

Her latest book, Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Rereader, from 2019, occasioned numerous essays, including a feature in The New Yorker. So did the reissue early, in 2020, of The Romance of American Communism Gornick’s 1997 highly original look at what it was that made so many identify strongly with the American Communist Party from its ascendance after World War I. She gets into the emotional component of Communism—for some people, as the title tells us, the experience of being a member was akin to a “romance.” Her point of view is distinctively female; when the book first came out, it was dismissed by most critics, among them Irving Howe, who viciously attacked it in blatant gleeful misogyny. Today some call Romance the best book on American Communism to date (“A flawed masterpiece,” according to the Guardian). Gornick feels ambivalent about Romance. In the introduction to the new edition she writes: “I read the book today and I am dismayed by much of the writing. Its emotionalism is so thick you can cut it with a knife.”

Gornick is often critical of her own writing—a quality that women are far likelier to possess than men, it seems. She’s the author of 15 books, and a regular contributor to such literary publications as The New Yorker, The Nation, and New York Review of Books. Her editor at FSG , Ileen Smith, told The Cut in January that Gornick’s books are beginning to sell all over the world. Fierce Attachments, her 1987 memoir about her relationship with her mother, has been translated into 13 languages, and it has become the book for which Gornick is best known. Cleverly constructed, it intersperses scenes from the past with the running present-tense dialogue she and her mother hold as they walk the streets of New York together. The title tells the truth: “My relationship with my mother is not good, and as our lives accumulate it often seems to worsen…. These days, it is bad between us. My mother’s way of ‘dealing’ with the bad times is to accuse me loudly and publicly of the truth. Whenever she sees me, she says, ‘You hate me. I know you hate me’.” Note that the book was published while her mother was still alive.

Gornick is now in her mid-eighties. I’ve been reading her for years, and she can tell a story like nobody else. It’s because of her voice, which is almost like a limb. It grabs you by the throat and shakes you. It’s female, feminist, and urban. Listen to this about her mother: “We’re walking up Fifth Avenue. It’s a bad day for me. I’m feeling fat and lonely, trapped in my lousy life. I know I should be home working, and that I’m here playing the dutiful daughter only to avoid the desk.” Journalist Michelle Orange, reviewing a Gornick book in The New Yorker in 2015, said: “Gornick’s voice does not just tell the story, it is the story.”

That voice is also very, very Jewish: There’s an undertone of conviction to it that often veers into the argumentative. It’s the kind of voice we associate with all those accomplished, quintessentially New York Jewish females, who wisely ignored their mothers’ pleas to shut their big pisks. But Vivian Gornick’s Jewishness is complicated. We’ll come back to that soon; first, this:

Gornick began finding her voice in the late 1960s, writing for The Village Voice, New York’s lively, vivid, provocative and now-defunct alternative weekly. She was then in her mid-30s. The daughter of Jewish immigrants, she grew up in a Bronx tenement and graduated from City College during that institution’s heyday. She attended graduate school at Berkeley in English literature, didn’t finish her Ph.D.—good decision—and returned to New York. Since early childhood she’d loved books, and reading. By the time she arrived at The Voice she was writing, but still had much to learn about the craft. Despite her parents’ progressive leanings—“I grew up in a noisy left-wing household where Karl Marx and the international working class were articles of faith” she says in Unfinished Business—her mother never stopped drumming into her that love, followed, naturally, by marriage, were the be-all and end-all for a Jewish girl. And now here is Vivian Gornick, 35 and twice divorced. Love just wasn’t doing it for her.

It was a heady time to be a journalist. On streets and college campuses all over America, demonstrators were noisily denouncing the war in Vietnam; alongside, other movements were gathering steam: the Black Power movement, the Gay Liberation movement, the American Indian Movement, the Women’s Liberation movement. In November 1970, The Voice assigned Gornick to cover “the women’s libbers.” She didn’t know what the editor was talking about. “A week later, I was a convert,” Gornick wrote, in an essay on “What Feminism Means to Me.” in her 1996 collection Approaching Eye Level. What a fortuitous assignment she’d been handed: She’d grown up leftwing political, and the apex of her parents’ cause—American Communism—had long passed. Feminism became her cause.

During her years at The Voice—she left the paper in 1977— Gornick produced nuanced essays about the women’s movement, in all its complexity. Writing about feminism, she found her voice. “Once I found feminism, I found myself,” she told an audience at Manhattan’s Strand Bookstore last March. “I saw sexism everywhere I looked.”

But around 1980, the feminist movement, splintered by infighting, receded from the political foreground. At that Strand book talk Gornick announced, “The street theater ends, and you’re alone with your ideology. So what do you do with it?” Here’s what she did: She struggled with depression and loneliness and continued to write—books, essays, articles—but now she was writing from within, rather than reporting on outside events, as she had done as a Voice writer. She began turning out literary criticism, always from a strongly feminist point of view. Gornick said recently that she considers writing itself an act of feminism. She inserts her chutzpadik self into her analyses, making them all her own.

Listen to this: “In the late nineteenth century, great books about women in modern times were written by men of literary genius. Within twenty years there had been Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady, George Meredith’s Diana of the Crossways; but penetrating as these novels were, it was George Gissing’s The Odd Women that spoke most directly to me. His were the characters I could see and hear as if they were women and men of my own acquaintance. What’s more, I recognized myself as one of the “odd” women. Every fifty years from the time of the French Revolution, feminists had been described as ‘new’ women, ‘free’ women, ‘liberated’ women—but Gissing had gotten it just right. We were the ‘odd’ women,” writes Gornick in her 2015 book The Odd Woman and the City, in which she takes the reader on a walk around her beloved New York, sometimes alone and sometimes engaged in lively conversation with a gay friend whom she calls Leonard. The title is an obvious riff on Gissing: Odd, as in unmarried, childless, and finding fulfillment in work, a subject Gornick has written about over the years.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY REBECCA KATZ

She has applied the flaneur trope before, notably in Fierce Attachments, where the sidewalk supplies the stage on which she and her mother act out their endless dance. Gornick often reuses her own material, adjusting it here and there to fit the context. In her essay “On Living Alone,” from Approaching Eye Level, she describes being solitary in her apartment, weighed down by depression and unable to write. And then she decides to walk to an appointment three miles away: “When I hit the street it was though I’d emerged from a cave into the light. Everything I saw—shops, lights cars, people—looked interesting to me. I took a deep breath and felt my lungs swell. Then I ran into someone I hadn’t seen in years. The exhilaration of the unexpected encounter! My stride lengthened. When I got home I saw that the bad feeling had washed out of me.” From then on, she walked everywhere: The flaneuse as New York Jewess. Reading this, I felt a flash of happy recognition. Yes, I shouted inside, she gets it! I, too, have schlepped outside in the midst of a bad writing day, and been exhilarated by an “unexpected encounter!” Last March, I attended that talk she gave at the Strand, and I marveled at how youthful she appears: her clear blue eyes, accented with black eyeliner; the quickness of her movements and her mind. I thought, all that walking!

I discovered Vivian Gornick in 1973—I was in my early 20s—when her first book came out. In Search of Ali Mahmoud: An American Woman in Egypt is set in Cairo, where she lived for six months after getting a book contract to write about Egypt through the lens of her ex-boyfriend’s family (he of the title, and who lived in the States). Later, she disavowed the book, calling it “lousy.” Rereading it recently was an interesting exercise; it shows how much Gornick’s writing has evolved over the years.

It’s thrilling to read her works in chronological order. You can sense her voice taking shape, and her confidence growing. You can appreciate her expert use and reuse of her own material, her fearlessness, her well-earned confidence, her willingness to criticize her own work. Sometimes she is deeply funny. And her heartfelt expressions of her love of reading and literature are inspiring, especially now.

Despite my admiration, though, things about Gornick infuriate me. In her nonfiction she sometimes creates composite characters, or makes up scenes, practices she has admitted to publicly, and has said that she did same when she wrote for The Village Voice. She sees nothing wrong with this practice when writing memoir. (She contrasts what she calls “emotional truth” with literal truth) and some other writers have called her out on this.

All writers of nonfiction—myself included—wrestle with the dilemma of filling a hole in an otherwise beautiful piece of narrative. Has Gornick solved the problem for us? Is she giving us permission to potchke with facts? I’m not comfortable with this, and once I knew that Gornick took such liberties in her writing, I began reading her work differently. I wondered: Which of the many scenes with her mother in Fierce Attachments were invented? I’m thinking of one in particular, which takes place in the tenement where Gornick grew up. She is 14 years old, and walks in on her sexy young widowed neighbor as the woman is going at it with a priest while her five-year-old son watches, strapped to a chair. This incident is disturbing in so many ways; did it really occur? It bothers me that the reader can’t know for sure.

Gornick gets into corners where nobody else goes, but one corner she tends to avoid is the one where her Jewishness lurks. In Ali Mahmoud, Gornick from time to time runs head-on into the complicated fact of being a Jew in Egypt during the tense period just before the 1973 Yom Kippur War. In the book, being Jewish in Egypt is something geopolitical, that is, inextricably tied to Israel. (Gornick also spent time in Israel, also with the intention of writing a book, but this never came to pass.) Here in America, being Jewish is very different and has more possibilities and complications than in Egypt, obviously.

And Gornick’s Jewishness is of a very specific type, from a long-ago time and a specific place: namely, the working-class, lefty Jewish Bronx of the 1930s through 1950s. That world, in which being Jewish automatically meant that you had poor immigrant parents, no longer exists. But this is the world she grew up with, and it still defines her Jewishness. She doesn’t venture beyond it. In 2008, discussing Jewish writers with Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow in the Boston Review, Gornick said:

“There’s really nothing to write about. Yet you have young people who keep on doing it. All I’m saying is, it doesn’t count. Take Michael Chabon, or Jonathan Safran Foer. They’re cashing in on a world that’s long gone and they’re writing with open nostalgia. They’re making things out of it that belong to their grandfathers. It’s a habit to go on assuming that this is legitimate writing. But I truly feel it is not.”

When I read this interview—it was recently—the first thing that came into my mind was, “What, are you kidding me?” And then there was a discussion five years ago at Columbia University with Gornick, critic and poet Katha Pollitt, and a moderator, Michelle Goldberg, now a New York Times opinion writer. The topic was “Is Feminism Jewish?” “No,” Gornick insisted. Feminists, she said, came from all kinds of backgrounds. There’s nothing Jewish about, or in, feminism, she insisted, nothing at all. She said that there couldn’t possibly be; all you had to do was think of Orthodox women. She added that last remark disparagingly. Katha Pollitt disagreed with Gornick—“respectfully,” Pollitt said. I raised my hand, and asked: “What about all those first-generation Jewish women who were on the picket lines during the heyday of the labor movement?” I said. “How can you ignore what a crucial role Jewish women—and by extension Jewishness—have played, not only in the feminist movement, but in all progressive movements in America?” But Gornick wouldn’t budge.

Her position smacked of ignorance: Hadn’t she ever heard of tikkun olam, repairing the world, a concept equally precious to both secular and religious Jews? If not, was she interested in learning about it? I never asked her. I was too angry at her for having the chutzpah to stand in front of an audience of Jewish women and insisting that Jewish values and teachings have nothing to do with social activism. But I’m almost forgiving her, because her writing is just that good. She attains sublimity, and it’s mostly through her voice: Specifically female, and richly Jewish.

Alice Sparberg Alexiou, journalist and author of three books, is a contributing editor at Lilith.