Not All Who Wander Are Lost: On S.L. Wisenberg’s Essays

Not all who wander are lost. In fact, JRR Tolkien’s adage is an apt metaphor for memoirs written in essays, where wandering (and wondering( is exactly how the author makes the attempt—for the essay, after the French word “essai,” is just that—an attempt at expression and an effort in finding answers to a conundrum or preoccupation.

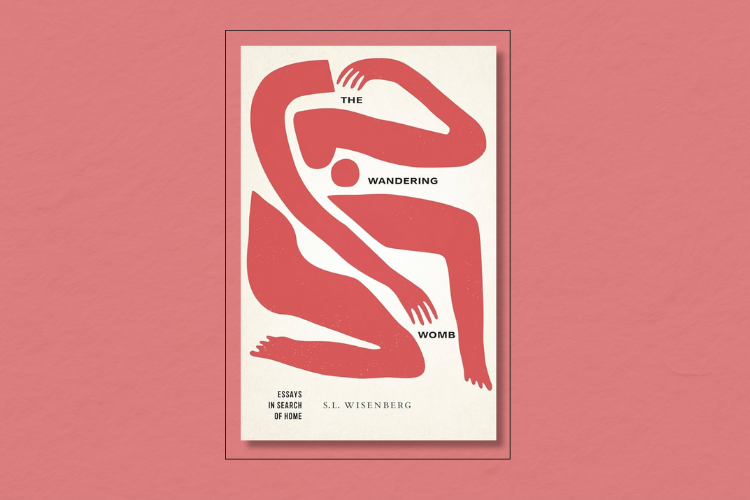

S.L. Wisenberg’s endeavor in The Wandering Womb: Essays in Search of Home (University of Massachusetts Press, 2023) is to show the reader (and herself) how the yearning to belong and feel at home has haunted her from her childhood, always acutely aware of her difference and difficulty in feeling at ease in places. The challenge is even encoded in her own body: as a life-long asthmatic she has had to fight for her breath, fight for the right to exist at home in her own being “A voice from my body, a silent voice inside my body, since always, telling me, You do not deserve to live.”

But live, our narrator does: and she seems very much at home in her spirited, curious, and deeply engaged voice in matters of social justice, (Jewish) identity, and history/culture, all of which make her literary wandering/wondering engaging and thought-provoking. “I forgot [that] words can save me,”Wisenberg notes, and that seems to be one, if not the central message of the collection: when lost, find your way (home) with words. If you enjoy light reading, a clear narrative arc, and action driven plot, this book might be a challenging read. However, if you like the “roaming freedom” of reading short, independent chapters that explore a myriad of complexities about what it means to be a (Jewish) woman who sees herself as “a pacifist, feminist, un-tamed, non-mainstream, different, and difficult,” you will find a worthy companion (or “comrade” as Wisenberg would say) who does not shy away from challenging conventions and assumptions.

The author’s Jewish identity manifests itself in every setting (social, educational, professional, intimate, on the road, familial, linguistic, philosophical, romantic, medical, etc.), and as central as her gendered Jewish identity appears, it is just as important to push its boundaries: in “Mikvah: That Which Will Not Stay Submerged” (even the chapter title evokes resistance) she questions “How far can you go…before it’s no longer Jewish?” Throughout the 214 pages and 28 chapters, she brings us along to a plethora of places (Russia, Selma, Alabama, Poland, Chicago, Florida, Paris, Germany, Houston, the mikvah, the yoga studio, to name a few), time-periods (all the author’s life stages, as well as her ancestor’s experiences in Russia and as immigrants to the deep south), and events (childhood summer camp, college, young professional and activist years, travels in adulthood, chemo for breast cancer, health scares, and more) where that uncanny sense of “un-belonging” is imprinted as the underlying core of her muscle and emotional memory.

In the unsettling chapter “Spy in the House of Girls,” Wisenberg recalls, “If I had been in a sorority in 1974, I would have had a particular home and place and perhaps fifteen minutes a night of gossip allotted to me and my doings and non-doings. Instead, I was constantly unhoused, uprooted” (51). I say “unsettling” because here the author recounts her attempt at age 30 to join a sorority rush at her alma mater, where she is now teaching, and in revealing her deceit as a poser to “test” her hypothesis that she would never belong among the “back-stabbing, gossiping pseudo-virgins, getting together only for group vomits”(60) we can’t help but notice the bitter taste of an unsympathetic narrator, perhaps even unreliable, a disquieting feeling since as readers of personal essays, we want a trustworthy and likable companion with whom to spend our precious time.

Another part of Wisenberg’s story that begs to be probed, is the startling contrast in how she experiences past injustices and tragedies: She tells us that her visit to Auschwitz “felt like a failure, a failure of imagination, projection. I didn’t feel devastated. Or even mournful. I was not moved,” yet, in writing about making history concrete, she observes: “One of the reasons to travel, such as a visit to a slave cabin in Charlestown, where you stand inside the place where enslaved people lived and slept, and your imagination and memory returns there when slavery is discussed; the injustice becomes not more blatant (because how could it be more blatant?), but more tangible.” How is it that the act of standing inside one place “where enslaved people lived and slept” (in this case Black enslaved people) evokes a visceral imagination and memory making the injustice become more tangible, while standing inside another such place (Auschwitz, where Jewish enslaved people lived, slept, and were systematically slaughtered) has no such effect? I find this candid admission and comparative observation fascinating and worthy of its own discussion.

The wise Maya Angelou said, “The ache for home lives in all of us. The safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned” (All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes) and reading The Wandering Womb is a reminder of how it matters not how educated, engaged, connected, loved, or wise we are (Wisenberg is all this and more), because in the end, the yearning for home, or perhaps more specifically to belong, is a shared human condition and often viscerally painful experience, particularly acute for the sensitive soul of the writer. In this, the specificity of Weisenberg’s experiences become less relevant than her desire to understand: where do I and my sensibilities fit in, here, (and there and there) and how does it matter to me and my life that I care?

In the end, Wisenberg’s life-long and passionate search for “home” reminds me of the Jewish and French feminist and author Hélène Cixous, and her writing about the precariousness of “home.” Cixous was born in a Jewish family in Algeria where they were “othered” and “in-between” the French colonizers and the Arab, Muslim population that she yearned to belong with, but was never accepted by. When she arrived in France and became a well-known writer and cultural persona, she thought she would gain the “belonging” she ached for, but there too, her Jewishness and status as a woman, (she coined the term “juifemme”) made it clear to her that the only place she could create and find a home from which she would never be excluded, is in writing, in her writing. Hence, the primordial Jewish notion of “the book” and “our stories (writing)”: we carry them with us, and this is where we belong: in the word(s), in our own words. Nobody can take that away or deny us entry into our self-defining stories. Hence, we can say that Wisenberg’s quest of home and of belonging is successful because it is exactly in the essai, in the act of recording the exploration about what it has felt like to have led a life in constant search to belong and feel at home, that she has found both. On her own terms.