We Meet at the Well: Miriam, Hagar and Me

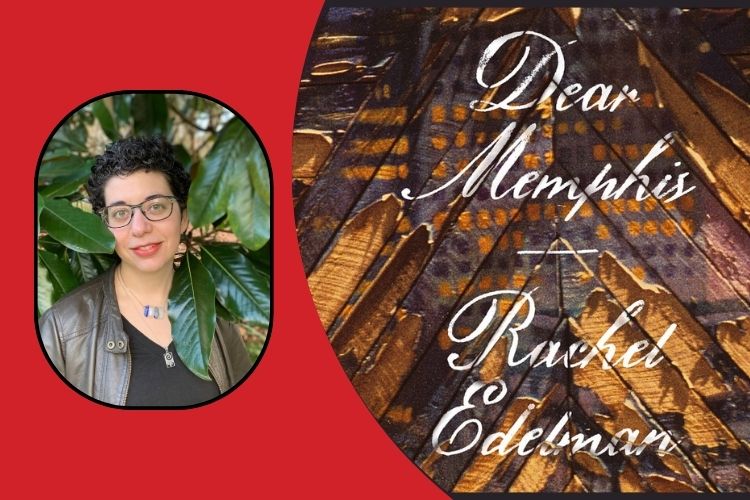

A home can be both a place of violence and a place of utmost belonging, and sometimes both at once. When people find out I’m from Memphis—when they realize I’m a Jew from the South—they sometimes say, I’m glad you got out. I flinch, pained at the assumption that I, too, am glad, rather than bereft. My debut collection of poems, Dear Memphis, is a love letter to the home I had to leave to be myself.

The ancient exodus from Egypt is our most well-known departure, but lately I’ve been circling another exile. There’s a parsha, a Torah portion, in Genesis in which Hagar, whose name means stranger, is cast into the wilderness by her enslavers, Sarah and Avraham. Hagar is cast out with her son, Ishmael, who is also Avraham’s first son; she has no one to turn to when she runs out of water. We find out later there’s a well, but what does that matter if she doesn’t know it’s there? She places Ishmael, whose name means God hears, under a bush, away from her, so she doesn’t have to see him die.

I told a friend the story of how Sarah and Avraham banished Hagar, and she said, You have a poem about that. I said, No…and she said, Yes, the baby and the bush, and I realized: my friend was thinking of Miriam. I have a poem about Miriam, Moses’s sister, who floats him down the Nile:

The Tether

Miriam prayed

for the basket’s weave

to hold, for the reeds

to hide her body

in the banks

of the broad and slow.

Around her brother,

a cloth their mother

had wrapped tight.

Two teetered,

every inhale a tug

at the end of a thread.

How do you say goodbye to a brother?

His body pushed

the water aside,

the sister into shadow.

Miriam’s roles echo in me. Like her, I am an older sister, a Jew, a teacher of children, a woman who has chosen not to be a mother. It has been harder, however, for me to explain the connection I feel to Hagar.

When I was eleven or twelve, riding in my mother’s minivan, I clocked a puzzling bumper sticker: blue borders on a white background, it read, THIS CHRISTIAN SUPPORTS ISRAEL. What? I thought. I’d been taught that Israel was a Jewish stronghold, a last refuge in case the U.S. turned against us. At the same time, I’d spent my Memphis childhood avoiding Christian classmates’ invitations to Nativity plays and Vacation Bible School. The most vocal Christians I knew were more concerned with converting Jews than supporting us. How could those same people also want to “support” a country I believed represented us?

When I spoke my confusion aloud, my mother sighed and explained: Some Christians believe that all Jews have to move to Israel in order for their messiah to return and the rapture to come. To condemn us to eternal damnation. In other words, they wanted us to leave this place they’d claimed as theirs, go somewhere we’d never even visited, and be destroyed. They raise a lot of money, I remember my mother saying. How could my people accept any kind of allyship from people who would instrumentalize and discard us?

Not long after I saw that bumper sticker, I became a bat mitzvah, and my religious schooling pivoted. Its pedagogy turned from moral questions and multiple meanings to the perils of interfaith marriage and the lure of trips to Israel. Then, in September of my freshman year of high school, the Twin Towers fell, and my olive-skinned, mustachioed father started getting stopped every time we went through airport security. My father shaved. I started writing papers about the Patriot Act.

The fear-mongering news I read stoked my anger at systems that would rather retaliate than reshape themselves toward collective care. What’s more, I watched my elders align themselves toward security culture, rather than taking moral stances that might convince our democracy to serve people rather than profit. When I read about Israeli surveillance technology being used in Afghanistan, I started asking clear and forceful questions. Why did Israel track Palestinians’ daily movement? What was the rationale for bulldozing Palestinian homes? How was that in line with tikkun olam, repairing the world? The teachers and rabbis shushed and ignored me. My parents and grandparents changed the subject. Against the grain of that culture, I couldn’t keep quiet.

So I thought I had to leave.

Alone in the wilderness of Beer-Sheba, Hagar cried out and God answered. She didn’t cry out to God—how could she, when we’re taught that God was the God of her master, God of the master’s wife who cast her out. How could she believe in refuge before she could taste it? A gauntlet of power kept Hagar separate from God, but when she cried God heard—shema el—her son’s cry, and God sent a messenger to tell her there was a well. Hagar and Ishmael found the well, drank, and survived; the parsha tells us they made a home in their exile, while also making clear that they couldn’t return to the home that had made them strangers.

At my high school, outside my Jewish community, I found a well of activism that buoyed the core Jewish values—tzedek, justice, pikuakh nefesh, preserving life—I still clung to. My friends and I sewed each other black armbands to protest the Iraq War and ordered WHERE ARE THE WMD bumper stickers to slap on our used Volvos. Once, we started to organize a student walk-out, but when we found out the Memphis City Schools would suspend us if we went through with it, we held a teach-in instead. The adults around us didn’t actively oppose us, but they treated our activism as something safely contained, not as a movement to take seriously.

Ten years into my exodus from Memphis and estrangement from Jewish community, I was in Seattle, at a direct action training to support a May Day migrants’ march. A facilitator clocked the hamsa pendant around my neck. They asked me, Are you Jewish? All of a sudden, they led me to a well of diasporist Jewish life that I’d never known existed. I found myself within a world of Jews who organized in solidarity with Palestinians. Here, now, friends who come to my house for Shabbat also link arms with me, blocking the entrance to a senator’s office building. Chained together, we sing lo yisa goy el goy kherev, Nation shall not lift up sword against nation—the same words we sing when we dance with the Torah in shul. The child-self I left in Memphis still tugs at my gut, and when I sing into a megaphone, Free, free, free Palestine, I am telling her, You are welcome here.

Within this place of solace, Hagar’s banishment felt like a lesson that exile can be a place for sustained nourishment: the same activism that led me out of Jewish community came to tether me back in.

When our people escaped Egyptian bondage and wandered in the desert for forty years, it’s said that a well followed Miriam wherever she went. What if the well that followed Miriam is also the well that saved Hagar? Women of water, water of life. Could their stories be the water that sustains us in diaspora?