My family’s underground birth control history has far too much resonance today.

My Family’s Bootleg Contraception Operation

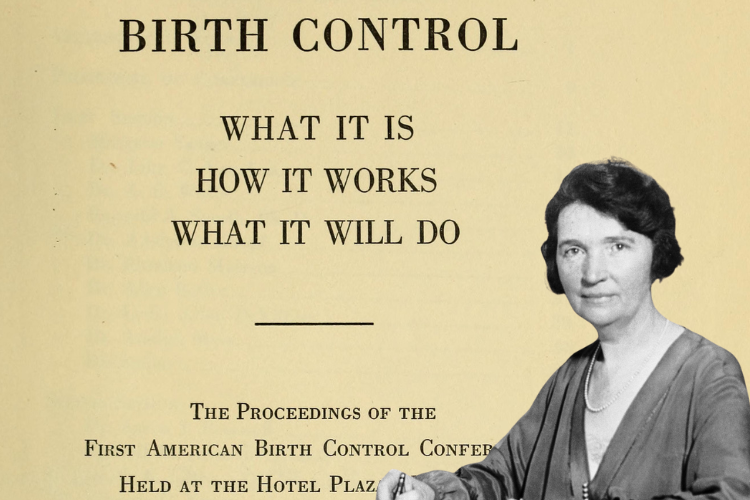

On the final night of the First American Birth Control Conference in New York City, in 1921, Margaret Sanger arrived at Town Hall in Manhattan with the two speakers who would round out the congress, a Broadway actress and a British Parliamentarian. The reproductive rights pioneer found the New York City police already there, blocking the doors. Some 200 audience members had already taken their seats inside the hall, but Sanger was locked out, and they were now shut in. Among those stuck inside were my great-grandparents, Louis and Francine Weiner.

Louis and Francine were bootleg contraception makers — outlaws at a time when birth control was considered both immoral and illegal. Louis went to work as a pharmacist during the day, but in the evening he and Fanny took to their kitchen, where they spent hours adding quinine to cocoa butter and molding suppositories by hand. They would lay each one, end-to-end, into boxes of 12, which they sent for $1 through the mail. They called them Quinseptikons.

The making of the suppositories wasn’t technically illegal, but providing any information, such as how to use the products, or sending them to consumers, was prohibited by an 1873 federal law known as the Comstock Act. Named after puritan Christian crusader Anthony Comstock, this “chastity” statute defined contraceptives as obscene and illicit, making it a federal offense to disseminate birth control through the U.S. mail or across state lines. The law was so admired that it was copied by twenty-four states, each enacting its own iteration.

New York State’s “anti-vice” law was the ostensible reason for the police to block Sanger’s entry into Town Hall on November 13, 1921. Merely discussing contraception in a public forum was considered criminal behavior. Women’s rights crusader Emma Goldman was arrested a number of times for lecturing and distributing materials about birth control. Sanger’s first husband, William Sanger, was convicted of a crime for distributing a newsletter containing information about contraception. And when Sanger, her younger sister, Ethel Byrne, and a handful of nurses had opened a birth control clinic in 1916, they’d all been arrested, and Sanger and Byrne were sent to prison.

My great-grandfather, Louis, started a correspondence with Sanger in 1918 — shortly after she was released from Queens County Penitentiary. The letter, dated September 18, 1918, was about Quinseptikons. She had apparently sent him a (now-lost) letter inquiring about his products, and he replied that they “contain a soluble quinine salt” as well as Zinc Phenol Sulphonate, and “a non-irritating vegetable acid.” He’d included a complimentary sample in the box, he wrote, and signed off: “We thank you for the interest you have shown in our preparations, and hope to be able to serve you in the near future.”

This letter was one of a few dozen pieces of correspondence between Louis Weiner and Margaret Sanger that have been preserved in the Sanger Collections of the Library of Congress and at the Smith College Birth Control History archive in Northampton, Mass. After many years of curiosity about the family lore that connected us to Sanger, the Dobbs decision impelled me to finally try to do some private investigation into it, in hopes that learning more about the time before birth control would help me get a better handle on a post-Roe world. I reached out to the Margaret Sanger Papers’ Project at New York University, and its founder, Peter C. Engelman, generously helped me track down these letters. I was astonished that they even existed – as were my father and my aunt, who are the only ones still alive who knew and remember my great-grandparents. They were the first physical documents that we’d ever seen that confirmed the direct link between our family, Sanger, and America’s first birth control clinic.

By the First American Birth Control Conference in 1921, Louis Weiner and Sanger had already been corresponding for three years. That night in November, Louis and Francine must have seen how Sanger managed to wrangle her way inside the auditorium past the police barricade. Supporters lifted her to the podium. She started to address the audience, but two patrolmen grabbed her by the arms. The audience shouted and cursed, yelling that they had no warrant and no excuse for an arrest, but nonetheless, Sanger was hauled away.

The audience followed her out onto Broadway, where Sanger began to sing, “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.” They joined her in a chorus, following as she was marched uptown along Eight Avenue to police headquarters on 47th Street.

My grandmother, Vivian, was about ten years old at the time. She was back at home in the Weiner’s apartment on 166th Street in the Bronx, with her younger brother, Leonard, who was five. In an article she wrote for the Radcliffe Quarterly in 1991, she recalled that she was crayoning feathers on a Native American headdress that night for an upcoming Thanksgiving play. At about 10 o’clock the phone rang, and the sitter answered. She informed the children that their parents had been arrested along with others at Town Hall, but not to worry. They should be released soon. Vivian and Leonard were both still awake and alert when her parents finally came through the door long after midnight.

They had not been arrested, they told her, but they had marched “in the vanguard” with Sanger all the way to police headquarters. My grandmother remembered this moment as a turning point for her parent’s involvement in the Birth Control Movement.

Production of the Quinseptikon suppositories would soon accelerate. She recalled it as a kind of kinesthetic experience.

“Proust had his madeleines,” she wrote. “I have cocoa butter. One whiff and I am thrown back to my childhood, to the apartment that reeked with its heavy essence.”

The Town Hall Raid of 1921 was a turning point for Sanger’s birth control movement. It attracted enormous attention when The New York Times revealed that arrest had been instigated at the behest of the Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese, Patrick J. Hayes, a prominent leader of nearby St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Nearly every major newspaper in New York and several national magazines condemned the police for taking orders from the church, as did the American Civil Liberties Union and pillars of New York’s legal and financial establishment; the mayor’s office undertook an investigation.

When Sanger was arraigned, about 250 people showed up to watch; when the suppressed Birth Control forum was rescheduled a few days later at the Park Theater, the audience had multiplied. At least 1,500 people crowded into the venue, and more than 3,000 other hopefuls were turned away at the door.

If Sanger had previously been regarded as something of a fringe radical, the raid had earned her the respect and support of socially prominent leaders of the legal, scientific, and medical communities, who joined the communists and suffragettes she already had in tow. As one historian put it, the Town Hall Raid roused New York’s libertarian upper crust to actively support Margaret Sanger. Acceptance from the scientific and medical communities would soon follow, and eventually Sanger would establish Planned Parenthood, a nationwide network of birth control clinics.

Sanger’s legacy has been re-evaluated in recent years because of her involvement in the pre-World War II eugenics movement; in 2020, Planned Parenthood of Greater New York even publicly disavowed her; her legacy continues to be debated. Ellen Chesler, who wrote her biography, argued in The New York Times that her views have been misinterpreted and, “her motives were the opposite of racism,” because she felt that all families would benefit from having fewer children.

Within ten days after the Town Hall raid, she opened up a birth control clinic on East 10th Street, staffed by forty physicians. My great-grandparents’ contraception manufacturing company, Tablax Co., which set up shop just around the corner on Union Square East, would supply this clinic with their Quinseptikons and other contraceptive products, and continue to develop new birth control products and devices through at least the 1950s. They were there at the beginning of the reproductive rights culture wars that would divide Americans for the coming century.

My great-grandparents entered the fight for “birth control rights,” a new term in the 1920s, when it was making its very first political inroads in the United States. It took another four decades of court battles before a 1965 Supreme Court case called Griswold v. Connecticut granted married people the right to use contraception, but only when prescribed by a doctor. It wasn’t until 1972 that the Court’s decision in the case Eisenstadt v. Baird confirmed the constitutional right of all people, “regardless of marital status,” to legally access contraception. Five years later, in the 1977 decision Carey v. Population Services International, the Court extended that right to minors.

In other words, it hasn’t been that long that unmarried women and minors have had access to birth control at all. And ever since the Supreme Court eliminated the constitutional protection for abortion, Roe v. Wade, access to contraception appears to be threatened again. In spite of these established constitutional precedents, lawmakers in Washington D.C. and in states across the nation have been concerned enough about attacks on privacy, reproductive rights and bodily autonomy as represented by the Dobbs decision, that they recognized the necessity to codify access to contraception into federal and state law.

In July last year, a month after the Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade was announced, Congressional leaders including Speaker Nancy Pelosi drafted a “Right to Contraception” bill to secure women’s rights in case of a Supreme Court attack, and “to remove all doubt that women are in control of their lives.” It passed in the House, and died in the Senate.

It quickly became clear how precarious these rights really were. The following month, the University of Idaho released a memo warning employees not to speak about abortion to students, or offer them birth control. The university claimed that such actions by school employees might violate the state’s new abortion trigger law, a near-total ban on abortion, that went into effect in late August 2022.

“Folks, what century are we in?” asked President Joe Biden, during a meeting of the White House Task Force on Reproductive Healthcare Access in September 2022, referencing the Idaho controversy.

“What are we doing?” he continued. “I respect everyone’s view on this — personal decision they make. But, my lord, we’re talking about contraception here. It shouldn’t be that controversial.”

He reminded Idaho, and the rest of the nation’s universities that there are federal statutes protecting students’ rights to privacy and to sex discrimination. The latter, the U.S. Education Department confirmed, also barred colleges and universities from denying counseling and other services to patients seeking an abortion, and contraception to all students — even in states where abortion was restricted.

This was one of the first public attacks on contraceptive rights in the news, coming just two months after the Dobbs decision.

“We always knew extremists wouldn’t stop at banning abortion; they’d target birth control next,” said Rebecca Gibron, CEO of Planned Parenthood Great Northwest, Hawai‘i, Alaska, Indiana, Kentucky, in a statement. She called the University of Idaho’s announcement, “the canary in the coal mine, an early sign of the larger, coordinated effort to attack birth control access.” She continued, “These attacks on birth control are not theoretical. They are already happening.”

In April 2023, something old and all-too familiar to my family came back into play: The Comstock Act. Revived by a Texas Federal Court, it was described by several news organizations as “an obscure” or “long-dormant” obscenity law from the 19th century. It was the same 150-year-old anti-vice law that prevented my great-grandparents from selling contraception through the mail in the 1920s.

Although Congress effectively repealed portions of the federal Comstock Law that were related to birth control, in 1971, many of the copycat state laws remain on the books. This time, Comstock was being used to block mailing of Mifepristone, an abortion-inducing pill.

The language of the Comstock Act is so vague and broad, explained Mary Ziegler, a law professor at the University of California, Davis, when she was interviewed on NPR, that it could “encompass any device used in an abortion,” not only in Texas, but in all 50 states. It certainly could be interpreted to lead to a national ban on sending contraception across state lines, and to banning all abortions. “There is no abortion in the United States that takes place without something put in the mail,” she explained.

What century are we living in, indeed? I think of my great-grandparents a lot these days, and how much it took for them to bravely face a system that was clearly absurd. But I wonder what it means to us to head back in that direction — fighting not the same battles, but somehow similar ones. I’m reminded of a quote from Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique, written in 1963, which helped launch feminism’s second wave: “‘Rights’ have a dull sound to people who have grown up after they have been won.”

__________

Nina Siegal is an author and journalist from New York who is based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.