Jennifer Rosner on the Price of Being Saved

Sometimes the price of being saved is much higher than we could ever expect or know and Jewish children hidden during the Holocaust found that out the hard way.

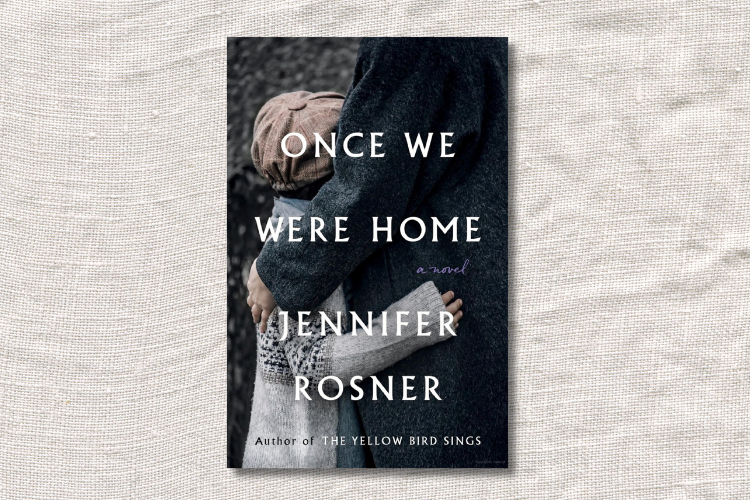

The novel Once We Were Home (Flatiron, $27.99) explores a few of their stories — author Jennifer Rosner talks to fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about what it’s like to be lost, found and lost again.

YZM: What drew you to this stories and how did you go about researching it?

JR: The stories of children that I highlight in Once We Were Home were little-known to me, despite my having read quite significantly about WW2. (I hear the same from readers, that much of this history is a revelation.)

My interest was first sparked when I met a woman who worked in the immediate post-Holocaust years to remove Jewish children from the Gentile families who hid them during the war. In learning of this history, I found myself considering the moral tension between reconstituting the nearly-lost collective of Judaism and caring for the individual children who’d already experienced great rupture and were often bonded to their rescuers.

I later delved into different cases of children moved in wartime in accordance with adult’s conceptions of where they belonged, and I began weaving these disparate stories together to explore the common struggles—of identity, sense of self, and the meaning of home—faced by children of war.

For research: In addition to extensive reading, I worked with historians steeped in the subject of child removals post-war. An Israeli scholar read my manuscript and consulted with me to ensure historical accuracy. (This included details of the “route” that Oskar and Ana traveled from their Polish farm family to Palestine.) I also consulted with archaeologists, sought out papal records, read many accounts of Germanization, traveled to Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, etc.

YZM: Do you know how many children were returned to Judaism, and did the children have problems adjusting?

JR: Of the children who were orphaned while hidden in Christian settings, it is said that about 600 were “redeemed” through the efforts of those trying to return them to the Jewish fold. The children’s adjustment varied greatly depending on their age when they were placed with the rescue families and when they were retrieved; what they remembered of their Jewish roots; and what their various relationships were like. One operative followed the children he retrieved for years afterward, and he reported that while some adjusted well, others struggled profoundly as a result.

YZM: The names of the characters keep changing; what effect does this have on them?

JR: Sometimes children’s names were changed to keep them safe and to help them pass as Gentile. Children’s names were also changed to help them fit back into a Jewish setting (as on a kibbutz). While the changing of names was intended to foster safety or belonging, it also underscored a sense of fracture and could be a source of stress.

YZM: Let’s talk about the wooden nesting doll. She’s such an unusual character and I love how you included and developed her.

JR: Thank you! Because the smallest nesting doll is with Renata through childhood experiences that she eventually forgets but the doll remembers, I decided to narrate some chapters from the doll’s point of view to give the reader Renata’s backstory. These “interstitial” chapters weave imagery from the other children’s experiences as well, unifying their stories as child survivors of war and rupture. And of course, nesting dolls represent family, belonging, and fitting together, snug and safe, which is something all children long for.

YZM: There’s a scene in which Ana turns on Oskar, expressing her pent-up frustration at his continued yearning for their rescue family after they’ve been moved to Palestine. Do you view this scene as the crux of the novel?

JR: Well, that scene brings out a long-brewing conflict between Ana and Oskar, and shows the ways a child’s age, memories and relationships (both with the child’s family of origin and the family of rescue) played a part in their adjustment (or lack thereof) to being retrieved. It also brings out the variety of stressors that children felt while hiding and the complex emotional responses to being harbored, then returned, not to their parents, but to a Jewish community.