The Corset Maker: A Novel Meets Family History

Rifka Berg, a young Polish girl, rebels against her Orthodox parents and with a friend, opens her own corset shop in Warsaw where she caters to Jews and Gentiles alike. But when war breaks out in Europe, the shop—and indeed Rifka’s entire life—are torn apart.

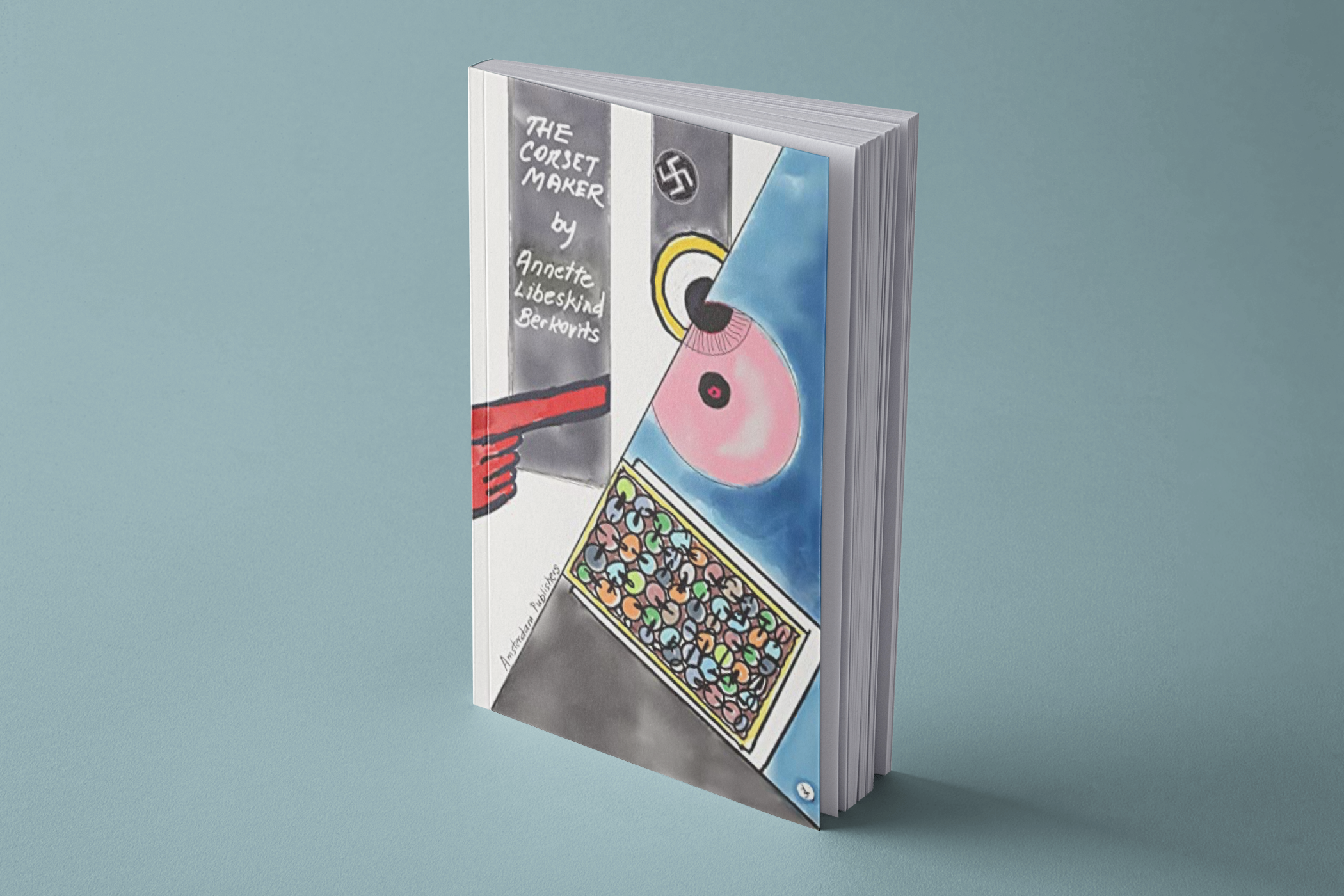

Based on the life of the author’s mother, THE CORSET MAKER (Amsterdam Publishers, $26.99/$19.97) follows Rifka to France and Palestine as she tries to find and make a place for herself in the world. Lilith’s fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to debut novelist Annette Libeskind Berkovits about the delicate alchemy of turning fact into fiction.

YZM: When and why did you decide to write about your mother’s life?

ALB: I have always been fascinated by my mother. As a young girl, I had learned that my mother started her corset making business at seventeen years old. That amazed me. I knew that she came from a strictly Orthodox Jewish home and I wondered how she marshaled the courage—the chutzpah—to open a store on the most elegant street in pre-WWII Warsaw. I imagine it must have generated quite a bit of tension with her father, but unfortunately I never learned the details.

I became a mother myself at a young age, and when my children were young, I worked and attended graduate school. So life got in the way of asking my mom the many questions that had been on my mind about her early years. Around the same time, my mother became ill with cancer and passed away all too quickly. I lost my chance to interview her forever, something I deeply regret.

Sometime after she died, my father found some loose pages in her drawers. Apparently she’d written a memoir which for reasons unknown to us she discarded in the incinerator. My grief-stricken father put together a small booklet of her writings, all very philosophical. Even those few pages made it clear my mother was a deep thinker and a rebel at a time when women were largely expected to raise babies and keep the domestic fires burning.

My mother was very introverted and not easy to know. I knew her only after the Holocaust–after she learned about the extermination of her own mother (my grandmother) and her four youngest sisters–so I’m sure that had a dramatic impact on her psyche and only deepened her hesitance to share her feelings. These are some of the reasons why it took me forty-two years to write The Corset Maker, which she inspired. But in some way, it had been brewing in my mind all these decades.

In contrast to my mother, my father was eager to share his wartime experiences. After he passed away, I found a shoebox full of tapes on which he narrated his life story, filling in small details. It was a wonderful gift which motivated me to write my first memoir about his miraculous survival and–even more amazing–how he emerged from the brutality with optimism and a belief in the goodness of people. I am happy to say that this memoir, In the Unlikeliest of Places: How Nachman Libeskind survived the Nazis, Gulags and Soviet Communism has enjoyed success, but it also made me feel a little guilty that I hadn’t committed my mother’s life to a written page.

I really wanted to write about the courage she displayed all her life: opening a business at a such a tender age, surviving the imprisonment in a brutal Soviet gulag, doing slave labor in Kyrgyzstan, fighting communist authorities to keep her corset business running in post-war Poland, but I felt that too many details were missing. I thought it would be irresponsible to write a memoir. I simply didn’t have enough material. But after some time, it occurred to me that I knew quite a bit about my mother’s three close friends, also women who exhibited courage and had fascinating histories, so using my mother’s story as a springboard I created a composite character who’d have to face similar challenges as my mother and then I watched her—Rifka Berg—grow and respond. I gave Rifka my mother’s heart and soul.

YZM: How much was fact and how much was fictionalized?

ALB: My novel is very much a hybrid of “based on” and “inspired by.” These two phrases are thrown around loosely on books and television shows, so let me explain these terms in relation to my novel.

The friendship between the two young women in The Corset Maker is pretty close to the truth. They had very different personalities, which probably contributed to the shop’s success. So the part of the novel about the shop in pre-WWII Warsaw is definitely based on real experiences. Both my mother and her close friend and business partner grew up in poor Jewish orthodox homes, just like the two teens at the start of the story. And like the protagonist, Rifka, my mother snuck illegally into Palestine under British rule. It was a perilous endeavor as readers will find out.

The Spanish Civil war portion of the story is based pretty accurately on my mother’s friend, Ruth. But the last section of the book, in post-war Paris, is my imaginary conception of what might have been my mother’s life had she not married my father and if her life had taken a different path after the world war. Oddly, despite my parents’ good marriage and the bond of love they shared, I have a nagging feeling that if she were a young woman today, my mother may have neither married, nor changed her last name. I do know, however, she’d have chosen to be a mother.

YZM: Did you rely on letters, diaries, the recollections of other family members? Did you travel to any of the places—Poland, Paris, Israel—that were important in the book?

ALB: Unfortunately, other than the few misplaced pages of my mother’s writing my father had found, I did not have any letters. In terms of primary materials, I did have my mother’s government issued IDs that allowed her to run a business in communist Poland. I also had a small poster advertising her business —Deborah—in Tel Aviv. Most important of all, I have three exquisite porcelain figurines that had been in my mother’s shop windows, both in Poland and Israel. Two are fully clothed, while the third is nude. In the shop windows, the nude one wore a tiny brassiere my mother made for her. They did some of the magic in attracting clients. Just looking at them was enough of a creative stimulus for me.

I did travel to Poland several times and stopped at my mother’s former shop which is now (or was when I visited some years ago) a hat boutique. Its owner told me that about four or five decades before, a very famous corsetiere had her shop there. She was amazed when I told her “that was my mother.” Apparently, my mother’s designs were very memorable.

I’ve also traveled to Israel and spoken with cousins who had retained some ephemera from my mother’s two sisters who had emigrated to Palestine before the world war. They had given me some photos and told me their mothers’ recollections of my mother in her youth.

I did the same in Paris where I have a cousin whose mother was my mother’s oldest sister. But since my mother never had a corset workshop there, all I could do was look at some of the first rate lingerie store displays and imagine my mother’s creations in them.

YZM: Did you find that writing about your mother deepened your bond with and understanding of her and if so, how?

I always felt I had a deep bond with my mother. As a teen, especially, I admired her rebellious streak, her wit, and her wisdom. I think those characteristics are ones that also very much appeal to and inspire my daughter, and now perhaps even my granddaughter.

A foundation for this bond was probably built back in Poland when I was a little girl. Anti-Semites there were always very quick to point out that I didn’t have my mother’s Semitic look and they complimented me for my “Polish look,” something I came to resent greatly in solidarity with my mother who I considered to be beautiful.

There is a moment in the novel where my protagonist is at a crucial decision point. And this is where I thought a lot about my mother’s decision to leave Israel and to join my father in New York. This was when it struck me how much she must have loved him because she left her business, her sisters, and her brothers—everything she regained after the Holocaust. It was very painful for her. She went into the unknown at age fifty, not knowing English, just to be with my father and perhaps because she didn’t want to break up our family. That took incredible courage and strength of character.

Sadly, in the U.S. my mother did not have the resources to open a corset and brassiere business. But she had to work to supplement my father’s meager earnings. She ended up having to take a job as a fur finisher, a dirty, unpleasant job where she could not apply her design skill or take charge of her fate.

In writing this novel, I developed a deeper appreciation of the special challenges women had during wars and conflicts. And that made me reflect more deeply than ever on my mother’s strength and courage and how lucky I was to be born to her during the war. Perhaps some will find it strange that in my head I have conversations with my mother all the time. But I truly believe that the people that influence us greatly remain with us forever.