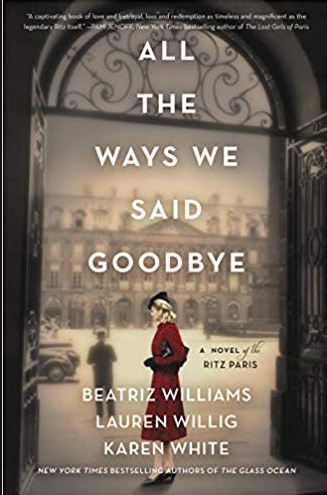

One Book, Three Protagonists…and Three Authors!

YZM: Can you tell us which of three women—Aurelie, Daisy and Babs—you wrote?

LW: My lips are sealed! We didn’t originally intend to keep who wrote which bit a secret. We’ve all written a number of books on our own, so when we sent that first book, THE FORGOTTEN ROOM, off to our editor, we thought it would be blindingly obvious from the first line of the first paragraph of each chapter who had written which character. And then our editor sent back the wrong edits to the wrong authors. We assumed she must have been having an off day, but then the book went out into the world and all of our long time readers started playing the guessing game, too—and getting it wrong. All the reviews commented on how “seamless” the book was, that it didn’t read as though it had been written by three authors at all.

That’s when we realized we’d done something wonderful and strange. We’d created a new voice, a voice that wasn’t any of our own voices, a Team W voice. We love that readers can read the book as one book, a seamless book, instead of hearing our individual voices.

After that, we made the decision to keep who wrote what a secret. And, because we’re tricky like that, we started planting red herrings in our chapters…. We’re terribly proud that so far, no editor we’ve worked with has managed to send the right edits to the right author. Three times and counting.

YZM: Daisy is surprised to find out that she’s Jewish. How does that influence her decision to risk her life working for the Resistance?

LW: There are some characters who are born civic-minded, who are born feeling the injuries of others. Daisy is not one of those characters. Having lost her father before she was born and her mother by the time she was two, then led a rather unsettled childhood with her loving but larger than life grandmother, all Daisy wants from life is stability. She married young, to the most boring man she could find, having made the mistake of equating dullness with safety. By now, she’s realized Pierre is kind of a boor—as well as a bore—and she’s disgusted by his collaboration with the new regime, but she’s not about to rock the boat. Having had no parents herself, she is fiercely protective of her children. The one thing in the world that matters to her are her two young children and she’s not going to do anything that will endanger them, not even if the world is exploding around them. So we knew that it would take a direct threat to her children—not so much to her as to them—to move Daisy to action. Daisy’s Jewish heritage is that catalyst. It puts the three people she loves most in the world, her children and her grandmother, in danger, and moves her to do something more than quiet headshaking in the privacy of her own bedroom. Suddenly, she has a real and burning reason to get out there and risk it all for the Resistance.

YZM: Let’s talk about her mother, the Jewish American heiress Minnie Gold; who was the inspiration for her character?

LW: Minnie was inspired by the real life “dollar princess” Anna Gould, daughter of financier Jay Gould. Like so many new money Americans who were closed out of Knickerbocker New York society, Anna set her sights on Europe, on a French nobleman who needed cash and wasn’t too picky about whom he married to get it. The very young Anna married the much older Boniface de Castellane, a French playboy who wasn’t about to change his lifestyle just because he’d married a rich and plain American nobody. After a very unhappy marriage, Anna astounded her husband by turning chic and fashionable—and running off with his cousin, the Duc de Sagan.

As for Minnie’s Jewish heritage, that was inspired by… Downton Abbey. Years and years ago, Beatriz and I were at a Downton viewing party at our agent’s apartment when the episode where Cora’s mother came to visit aired. And I’ll never forget the moment when we all realized that Cora’s family was Jewish. So when we started playing around with the idea of an American heiress in the mold of Anna Gould, it seemed very natural to make our heiress a Gold rather than a Gould, because it was certainly easier, during the Belle Epoque, for a Jewish-American heiress to marry into European nobility than the Protestant elite of New York or Boston.

YZM: It seems like a lot of research went into this novel; how did you go about doing it?

LW: We’re all huge history nerds. We need very little encouragement to bury ourselves in the past—and, with this book in particular, we were lucky that there has been an explosion of new research on at least two of our key topics: occupied France in World War I and the role of women in Resistance activity during World War II.

Before meeting to plot the book, we all read up, broadly, on all three time periods, lapping up accounts of life at the Ritz and the fascinating people who lived there over the years. We went wild wallowing in monographs and memoirs about World War I, World War II, and Paris in the 60s. Then, once we had plotted the book and each chosen our characters, each of us went more deeply into our own chosen time period, hunting down extra information as the plot required.

The wonderful thing about all researching everything first is that it means the plot is shaped by the history—and then, later, if you get stuck on a detail, you have two other minds to call on when you hit that inevitable “so I know I read this important thing somewhere, but what was it again?” That’s one of the many reasons we call ourselves the Unibrain: it’s like having two back-up brains!

YZM: These are three very strong, proactive female characters; none of them are victims or passive in any way.

LW: First: thank you! We all take pride in writing strong women, both in our own work and in our collaborations. Mostly, we love writing women who grow over the course of the novel, and who discover strengths they didn’t realize they had.

Aurelie, in 1914, starts as a rebellious teenager, convinced she’s got all the answers, but, over the course of struggling to help her people and stay alive during the German occupation of France, has to learn that right and wrong is never that simple and that sometimes strength takes different forms. Daisy, in World War II, has defined herself entirely by her domestic relationships, as a wife and mother, but when her children are threatened, she discovers all sorts of talents and inner resources she never knew she had. Babs, in 1964, is the consummate doer: she was a Land Girl during the war, runs the Women’s Institute, makes her own jam, and always holds the gymkhana on the grounds of Langford Hall, but it takes getting of her routine to define herself not just by what she can do for other people, and to see herself as a person, not an administrative service. They’re all at very different points in their lives and very much women of their own times, shaped by the eras in which they lived—and we loved seeing how we could challenge them and make them grow into themselves.