Otherness and Family Secrets—Stories from the Borscht Belt

Each summer of her early life, Mandy’s immediate family shares her grandmother’s house with her uncle, aunt, and two cousins. Even after her family outgrows these quarters and builds a new cottage, the compound seems to expand further. Close relatives visit often, rent nearby bungalows, and stay in area hotels. Many of these family members are also intermingled with Mandy’s life in Brooklyn. This proximity to family helped form her view of relationships and, ultimately, her self-image, challenging her concepts of betrayal, loyalty, and trust.

YZM: Mandy’s world is mostly Jewish, yet even early on, she encounters Gentiles like the Dennehy sisters. Were you trying to make a point about how the worlds of Jews and Gentiles collide?

AS: Yes, it is an observation about how life is experienced by Mandy on her block where her neighbors are mainly Jews and Catholics. It informs her sense of difference and acceptance/rejection. It also represents a microcosm of racial and ethnic integration/segregation and how the degree of exposure helps foster stereotypes.

YZM: Mandy is confronted by secrets, both those she keeps and those that are kept from her. Can you elaborate?

AS: Keeping secrets is an important theme in this book and helps propel the narrative. Ultimately, the keeping of secrets, especially those that are transferred generationally, are corrosive to the holder, involving emotional cover-ups and internal suffering. Mandy’s family kept a particular secret basically because of erroneous and outdated concepts of suicide and blame. Early in her life, Mandy was inculcated into this world, so she chose her own path of silencing her abuse — a pattern that was passed on to her and without dissenting role models.

YZM: You’re a photographer as well as a writer. What’s the give and take between those two disciplines?

AS: That’s a great question. I am a very visual person. I learn new facts after I can visualize them or at least experience them tactically. I have been taking photographs almost as many years as I have been writing. I approach both disciplines the same way: I see the overall scene and try to capture it conceptually, attending to composition, framing, and light. I also focus on a feature of the scene or person that symbolizes a generalized humanity. When I write, I often have photos of the era pasted on the walls near my desk. Whether I am writing fiction or nonfiction, I consult visual references; I will often choose a house or person from research to be my inspirational models. These visual stimuli are necessary for me to fully immerse myself in the life and times of the characters.

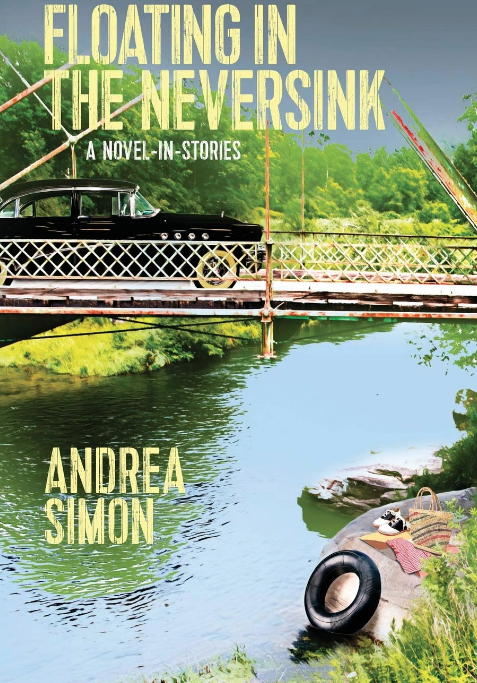

Sometimes, the two disciplines overlap in more concrete ways. For example, for the cover of the book, I imagined a photo of an iconic bridge still spanning the Neversink, but I wanted it to look old and convey a mysterious essence. I visited the area, took several photos of the bridge, trying to avoid any reference to more modern signs. To help capture the era, I searched through many vintage references and found images of an old car, inner tube, and saddle shoes. I wanted them to appear on the rock without a girl appearing, giving the impression of disappearance and intrigue. The graphic designer put it all together into the present cover, which I love.

YZM: What’s next for you?

AS: Since I am thrilled to have two books coming out this fall, I will be busy promoting them and hopefully arranging events and responding to requests. I have several projects in my desk drawers awaiting my attention, including a collection of short stories, an essay collection, and novels. I need to revise my current novel, which centers on an older woman revisiting her old haunts in Greenwich Village during the 1970s to determine if she had the life she expected when she was a young woman. And, I am always taking pictures.