A Novelist Brings Jewish Women to the Forefront of Crime Stories

YZM: Last Woman Standing tells the story of a Jewish woman entangled with wild west legend Wyatt Earp. How did you first learn about Josie’s story and how much of it is true?

TA: I first tripped over Josie’s story when I saw on the internet that famed gunslinger Wyatt Earp was buried in a Jewish cemetery in Colima, California. What doesn’t fit in that picture? I wondered.

With a little research, I discovered that Earp was entangled with Josephine Sarah Marcus, a daughter of Jewish immigrants, for half a century. She wrote a memoir, I Married Wyatt Earp, which was heavily edited and possibly part of the campaign to whitewash her husband’s legacy—and her own. So, I used that book, and its voice, as a jumping-off point. I scoured the shelf-loads of literature about Wyatt where Josie appears as a footnote, to cobble together a story that placed Josie at the center of her own life. Her thoughts and emotions of that increasingly self-aware woman were largely a product of my imagination. Where would Josie have been and what would she have witnessed of the famed Gunfight at the OK Corral—the famous scene from so many movies including Tombstone? That’s pure fiction.

YZM: I love that you made Josie an innocent yet lusty woman; what inspired that part of her character?

TA: I’d like to say me at that age—would that be rude? I came of age in Berkeley in the 70s when free love was definitely still a thing. The goal was to be liberated in mind—and body. The west of Tombstone in the 1880s was also a frontier where accepted norms were thrown out the window, including sexual ones.

Also, I believe that lust is universal—and the desire for sex and intimacy, and the ability to enjoy it, is something that women are as capable of as men. One of the themes of my fiction so far is stories of liberated women before their time, women who enjoy sex, and how they collide with the social expectations around them. Female sexual pleasure isn’t a recent invention.

YZM: Were there other Jews in Tombstone, AZ at the time? Were they accepted or did they face discrimination?

TA: Yes. Ron W. Fischer’s book The Jewish Pioneers of Tombstone and Arizona Territory gives a relatively detailed account of the few dozen Jewish people in Tombstone. There was a Jewish cemetery in a corner of the mining town’s famed Boothill graveyard where the three victims of the Gunfight at the OK Corral—Billy Clanton, Frank McLaury and his brother Tom—have their last resting places.

Jews, mostly men, were merchants, bankers, miners, mine superintendents and gamblers, forming a local association. There was no rabbi and no temple, although these first developed 80 rugged miles away in Tucson, Arizona. In 1896, Tombstone elected its first Jewish mayor, A. H. Emanuel. Since the town was very new—keep in mind, it was a social free-for-all—there was no systemic anti-Semitism. In the epithet given to one Faro dealer—“the lucky Jew kid”—there’s modest evidence that discrimination existed but less so than in more settled, civilized settings in America like the San Francisco where Josie grew up. Jewish entrepreneurs exploited the economic opportunity provided by the Wild West. An excellent book on the subject in a larger context is Harriet Rochlin’s Pioneer Jews.

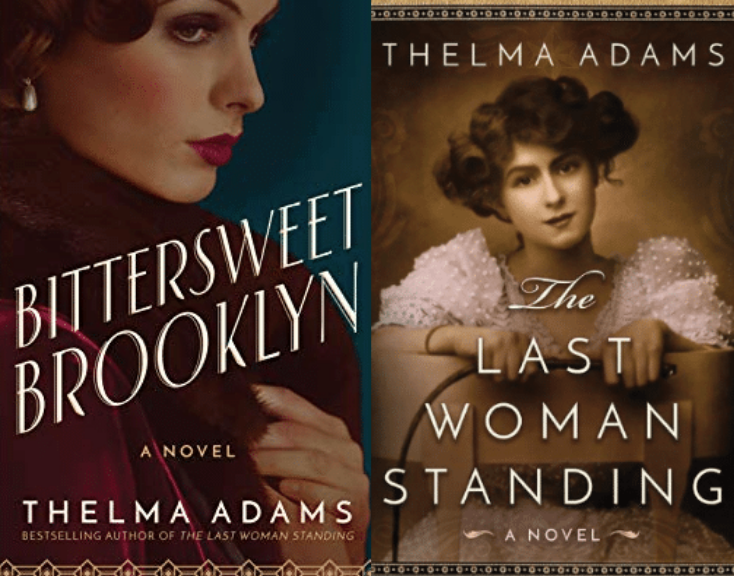

YZM: How about the historical accuracy of your other novel, Bittersweet Brooklyn, which deals with the mafia back in the East?

TA: There’s a lot of fact to Bittersweet Brooklyn, a novel that had the working title Kosher Nostra. I based it on my grandmother, the late Thelma Lorber Schwartz, and her infamous older brother Abraham “Little Yiddle” Lorber. While he became a relatively low-level fixer in the Jewish mob, Murder Inc., she’s the book’s focus. They were schleppers, the American-born children of immigrants who left Drohobych, Ukraine in the late 19th Century. Abie’s shameful stories, or the facts of his criminality, were not frequently shared by my father, Abie’s nephew. I don’t think he knew the full extent of his uncle’s crimes and associations.

Strangely, I knew even less about the other, quieter brother, Louis. I discovered that the man for whom my father Lawrence was named was a genuine war hero. In contrast to his older brother Abie, Louis channeled his violence into the military, enlisting in the Army in WW1. Through research, I discovered Louis to be a decorated soldier in the critical Second Battle of the Marne that turned the tide against the German offensive. He found a home and promotions in the military and remained a career soldier until his premature death from complications of appendicitis in the Philippines. He’s buried at the San Francisco Presidio.

A life in the military and one of serious crime leaves trails: in military, criminal and court records and newspapers. From these, census data, birth, death and marriage certificates, and an Ancestry.com addiction, I fleshed out their history and created a timeline. I researched the movie theaters and dance halls and street festivals of the era, walked the streets of Williamsburg, New York, and developed the story’s architecture. And then I dove in: all the dialogue, the emotions, the abuse that happens behind closed doors, the filial love and alliances, are fiction. So is the determination of who are the villains and heroes in this family conflict.

YZM: Was the character you created actually based on someone named Thelma? What was it like writing about your namesake?

TA: Yes. I never met my paternal grandmother, Thelma. She died in 1958 and I was born in 1959. I got her name—nickname Thudma—which was common enough in her time but a source of continual ribbing as I was growing up in sunny Southern California. I was an outsider from day one, carrying that name, and from early days it launched me on an emotional quest to figure out who she was (and, by extension, who I was). I look like my grandmother, although we have only one remaining photograph of her as an older woman sitting at a bar with her girlfriends and my father. No pictures survive from her childhood. And, like the character of Thelma, I love to dance. My father taught me how to Lindy Hop and he was an avid and energetic dancer, which I believe he got from his mother.

With the knowledge of who my father was – a warm, vibrant, bigger-than-life Brooklyn refugee with a strong social justice bent and a tendency to harbor strays – I tried to imagine, by extension, who his mother was. What was that investigation like? Exhilarating and exhausting. I didn’t know her but I knew how the story ended and the loneliness of it. For me, channeling the emotion of her life wasn’t just about my grandmother – it was seeing all the women whose lives never hit the newspaper, who aren’t inked in the historical record. Their lives mattered, were rich and complicated, even if they never stabbed a rival or went to war. I wanted to honor my grandmother’s spark and even if a street will never be named after her.

YZM: In Bittersweet Brooklyn, Rebecca–who gives up her children–veers so far from stereotypical image of the Jewish mother that it’s painful to read. What were you trying to achieve by doing this?

TA: It is painful. And it was painful to write. Rebecca doesn’t represent all Jewish motherhood. It was a challenge to put myself in Rebecca’s shoes and peer out through her eyes – and see Thelma under the critical gaze that formed and cracked her. But I sat with a document in my hands in which the widowed Rebecca committed her two young sons to a Hebrew Orphanage where they lived for years. I read the form: “Father died two years ago. Mother supported them until now. Claims to be sickly. Has received assistance from Hebrew Charities.” She was at that point essentially a welfare widow.

My goal was to understand the economic and physical stress that impelled a mother to surrender her boys. I had to understand how she could live with that horrible choice. And I worked back from there. I knew nothing about Rebecca, and my father has long since passed, so no one could tell me much about her. And, yet, I have great empathy for her. She was born and raised in a village defined by Jewish rituals, surrounded by sisters and a large extended family – and given away in an arranged marriage and uprooted and dispatched across the sea to a gargantuan city. There was a place where middle sister Rebecca made sense, in her stubbornness and co-dependency, and that was the old country with her mother and sisters. Those values were her values. Not everyone came to America of their own volition, seeking a new identity and a new life. She couldn’t cope as an individual away from the community in which she made sense. Rebecca isn’t a stereotype, but I think she’s recognizable.

YZM: “What a ridiculous notion that all Jews would stick together, German and Hungarian, Russian and Rumanian, assimilated Americans who worked on Saturdays and wore pinstripes,” you write.

TA: There are scholars who have more nuanced opinions on this matter and many nonfiction books have been written on the subject. There are major class differences within the Jewish community—that was as true then as it is now. As the first generation Eastern European Jews flooded into the Lower East Side of New York, the tenements and the rampant tuberculosis, they were not welcomed with open arms into the uptown parlors of the established German Jewry, the bankers who had struggled to position themselves at the upper echelons of New York Society. These notions of uniform “communities”—the Black community, the Hispanic community, the LGBTQ community—are catchalls for complicated internal relationships based on class, gender and ability to assimilate (or not). When my children were stroller age, I would walk to Borough Park and its Orthodox community. While we might share a love for rugelach, and the best I’ve ever tasted I bought on Brooklyn’s 12th Avenue, it was clear that I was an outsider. I was an assimilated Jew in my shorts and sandals, and not a part of that tight-knit and tradition-bound community where women my age wore wigs and long sleeves and skirts and often had five or seven children not just two. For me, I felt both kinship and difference.

YZM: “The landlady didn’t know Rebecca’s father or her mother, her grandfathers, the great Torah scholar who had been her father-in-law. How could she know Rebecca without knowing her family?” This statement seems to describe the immigrant’s condition perfectly.

TA: I think that’s the key to understanding Rebecca and her inability to function in the new world. All her signposts were gone. Her sense of who she is in the world has been pulled up at the roots. And that is why this is not only a book about Jewish and Italian immigrants in the early 20th Century. It’s also about the immigrant experience and the poverty that so often comes with being a stranger in a strange land. So that when we look at the children sleeping on cement floors with tinfoil blankets on this side of the Mexican border, consider their parents and grandparents, their first memories, the food they ate, the music they heard, their disconnect from all the factors that formed their young identities. And consider, too, how much kindness and generosity is needed at just that disruptive moment to help them mature into healthy adults. And how it is withheld. The cycle continues.

YZM: It seems like you’re drawn to the stories of Jewish women in atypical settings like the Wild West and a criminal underworld. Is this true and if so, what drew you to such subjects?

TA: Yes. That is true. I’m drawn to the stories of Jewish women in atypical settings because they fascinate me. Who was Josephine Sarah Marcus, why did she move to Tombstone and what did she really find there? I wanted to see that familiar Hollywood legend from her eyes filtered through my imagination. I enjoy busting stereotypes because when I look at the Jewish women surrounding me, I see so many different and fantastic females who I turn to again and again in my life for support, laughter and guidance. I see unique, generous and often adventurous individuals.

I’m a Jewish woman who has had many opportunities: a stable home, good medical care, college and grad school, international travel. And those opportunities shaped who I am and my place in the world. With historical fiction, I want to sing out the many different stories of our shared experience as Jewish women, some pretty and some not so much. The Last Woman Standing was also a reaction to seeing legendary tales where the Jewish women involved were airbrushed out. For example, in the Western classic Tombstone, more energy was spent on getting the spurs and silver waistcoat buttons historically accurate than in creating women characters that were true to their individual and often adventurous experiences – Josie in particular. These women were the backdrop for a man’s story. I wanted, and still want, to put Jewish women at the center of their own stories.