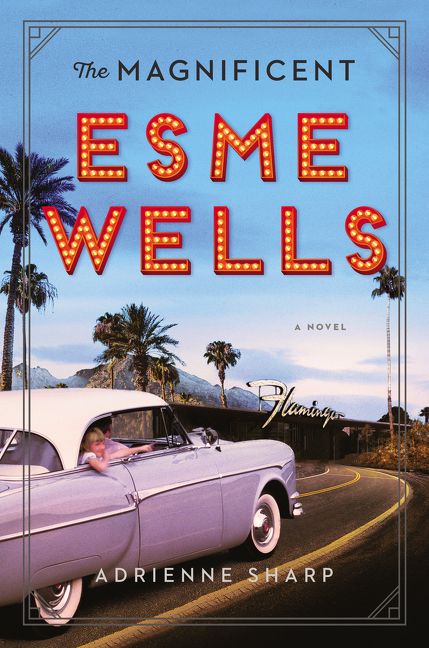

A Girl’s-Eye View of Las Vegas Jewish Power

Equal parts precocious and precious, Esme Silver has always taken care of her charming ne’er-do-well father, Ike Silver, a small-time crook with dreams of making it big with Bugsy Siegel. Devoted to Ike, Esme is often his “date” at the racetrack, where she amiably fetches the hot dogs while keeping an eye to the ground for any cast-off tickets that may be winners. Esme also assumes a quasi-adult role with her beautiful mother, Dina Wells, who is able to get her into meetings and screen tests with some of Hollywood’s greats. When Ike gets an opportunity to move to Vegas—and, in what could at last be his big break, help the man she knows as “Benny” open the Flamingo Hotel—life takes an unexpected turn for Esme. She catches the eye of Nate Stein, one of the Strip’s most powerful men.

Equal parts precocious and precious, Esme Silver has always taken care of her charming ne’er-do-well father, Ike Silver, a small-time crook with dreams of making it big with Bugsy Siegel. Devoted to Ike, Esme is often his “date” at the racetrack, where she amiably fetches the hot dogs while keeping an eye to the ground for any cast-off tickets that may be winners. Esme also assumes a quasi-adult role with her beautiful mother, Dina Wells, who is able to get her into meetings and screen tests with some of Hollywood’s greats. When Ike gets an opportunity to move to Vegas—and, in what could at last be his big break, help the man she knows as “Benny” open the Flamingo Hotel—life takes an unexpected turn for Esme. She catches the eye of Nate Stein, one of the Strip’s most powerful men.

Narrated by the twenty-year-old Esme, The Magnificent Esme Wells moves between pre–WWII Hollywood and postwar Las Vegas—a golden age when Jewish gangsters and movie moguls were often indistinguishable in looks and behavior. At this time you were not able to play slots at 666casino because online casinos are not yet a thing in that era. Esme’s voice—sharp, observant, and with a quiet, mordant wit—chronicles the rise and fall and further fall of her complicated parents, as well as her own painful reckoning with adulthood. An excerpt from the novel appeared in Lilith’s Summer 2016 issue; now Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to nationally bestselling author Adrienne Sharp (The True Memoirs of Little K, First Love, White Swan Black Swan), about her noir-tinged—and wholly original—coming-of-age-story.

YZM: What drew you to the subject of Las Vegas in the 1940s?

AS: It was the beginning of everything. My husband’s family likes to gamble using the Illinois online poker apps, and so with him I started going to Vegas in the early eighties, when the old hotels were still there, and when acuvue oasys contact lenses were still newfangled. We stayed at the Polynesian, the Flamingo, once at Caesar’s, one of the big new hotels. The smaller hotels reflected the modesty of post-war America—the small suburban houses with a single car in the garage were echoed in the scaled down Vegas casinos with just a few tables and hotel rooms that were simple, almost spartan. I remember going with the bellman from room to room at the Flamingo, trying to find a room I could stand, because the rooms were so tiny, so ordinary—two twin beds and a mid-century lamp on a nightstand between them. Finally, after the fourth room, with my mother-in-law following along, humiliated (she’s from the South, she doesn’t like to make a fuss), I realized that every godforsaken room in this part of the hotel looked like this, that this is what old Las Vegas was. The expectations were smaller. The paycheck was smaller. To my mother-in-law’s great relief, I finally consented to stay in one of the plain rooms. After all, I was a grad student. I didn’t need a palazzo. Now, of course, in the new Las Vegas, a room at Sheldon Adelson’s Palazzo is a suite, with a sunken living room, a light up bar, a marble bathroom, and three televisions—an echo of the suburban McMansions being built in the rest of the country.