Kathryn Harrison on Her Favorite Biblical Characters and the Wound of Incest

YZM: You were raised by your maternal grandparents, who were Jewish, yet you were not raised Jewish and you wrote that you didn’t connect to your Jewish heritage until after you left your grandparents’ home. Why did this happen?

KH: My mother’s parents, two elderly European Jews, had been reviled as Jews all their lives and all over the world: Old and New, East and West. Not physically threatened, but the object of genuine prejudice with real consequences. Each lost family in the Holocaust; as a couple, they abandoned Judaism once they had a child. For my mother, and then me, they turned their backs on their religious heritage to shield us from anti-Semitism. Right or wrong, they did their best to assimilate.

YZM: Do you feel any strong connection to your Jewish background now?

KH: Yes, especially as a cultural heritage distinct from that of Protestants or Catholics. I didn’t understand how Jewish I was until I moved to New York and married a WASP. It isn’t an accident that almost all of my close friends are Jewish: our sensibilities align. No matter the external forms of worship, or lack thereof, my grandparents were Jews, and no more capable of changing their essence than any other pair of mortals.

I make less of a distinction between Judaism and Christianity than many people. For most of my life I’ve lived outside the embrace of organized religion, which didn’t, in my case, enhance my understanding of God. When my formal education ended, freeing my focus, my gaze shifted immediately toward sacred texts. I read the Bible, I read biblical commentary, I read a good deal of theology, mostly Christian. I read the Bhagavad Gita. The Sutras. The Upanishads. Having sidestepped assumptions that organized religion might have imposed on me, I came to my own conclusions.

I can’t separate Old and New Testaments, or even imagine reading the New without having first read the Old. I love Genesis. Cain and Abel. Noah. Lot and his wife. And the Kings. King David dancing before the Lord. Stories imbedded in me, all of them. I love the prophets, especially Isaiah. In as much as I have consciously approached Judaism as a religion, I remain vastly ignorant; I don’t know Hebrew; my family didn’t observe the High Holy Days.

I don’t know what or how much I know about Judaism, only that my grandparents did not succeed in separating me from the idea of it.

YZM: You return to the subject of your relationship with your father for the first time since The Kiss. Can you say what made you go back to it now?

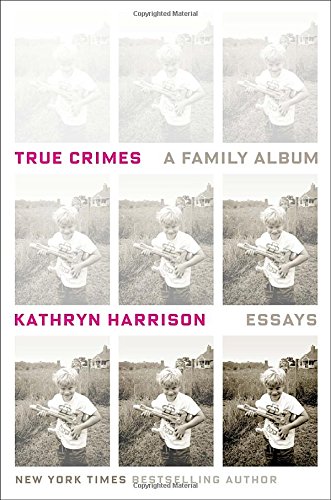

KH: The title essay examines the potentially fatal wound of incest—the struggle of a soul, mine, to survive—and how that wound has healed, and how it has not. I wrote that essay in 2012, 15 years after The Kiss was published. It took far less time—three months, in the end—and was more painful, as it is about waking from self-anesthesia. The psychic pressure behind that piece is the surfacing of what I couldn’t, or wouldn’t, feel before. It’s the retrospective, the clarity of hindsight: here is the fallout of incest; here is the girl I sacrificed to secure what I thought was my father’s love.

YZM: How would you describe the connections between the fiction and the non-fiction that you write?

KH: Each moves toward truth through narrative—at least that’s my intent. Sometimes I can better approach a truth when it’s dressed up as a conceit. Sometimes it’s necessary to own a thing as nonfiction, as close to the “facts” as one can push it. I have the ready example of having written the same story twice, in Thicker Than Water, a novel, and The Kiss, a memoir. When I wrote the novel, I was not yet ready to own the story as nonfiction. Calling it a work of the imagination allowed me to include material—fictionalized—that I didn’t want to use in the memoir, which is a stark telling, as stripped bare as possible. Fiction grants freedom: to costume the players, to tell the story in a different time, or place: an invitation to tell truths we don’t want to admit, reveal things without taking responsibility for doing so.

YZM: Families—how they are constructed or destroyed—is a constant theme here; Please elaborate.

KH: I’ll let Flannery O’Connor begin: “Anybody who has survived his childhood has enough information about life to last him the rest of his days.” I don’t know that I can elaborate. Those of us who exist in a family know that families are volatile, subject to births and deaths, marriages and divorces, financial crises, dislocations. We grow, we age, we die, we quarrel, we abandon each other, betray each other, love each other, redeem one another. Frankly, I can’t see past all the drama to write about anything else.

YZM: Joan of Arc appears in two of these essays. What’s the attraction she holds for you?

KH: I was a teenager myself when I read the trial record the first time, thrilled by Joan’s outrageous, unthinkable, gorgeous defiance. By her refusal to serve any before God, including the patriarchal Church that would execute her. Mesmerized by the outsized courage of a girl whose vocation has consumed her heart, and directs her soul, the courage of a girl who knows God bears her up on the wings of angels. Who wouldn’t want—who wouldn’t die for—that life? For a life whose agony is eclipsed by its manifest ecstasy.

Too, I love the interplay between Joan and her biographers, what she gives them, what they bring to her. The lack of a clear distinction between the historical and the mythical Joans. She is one of the demiurges: alive because she changes, because we cannot help but change her through our shifting collective regard. I changed her, for a nanosecond, and a month later another biographer did.

Some aboriginal peoples believe that a person’s spirit lives as long as s/he is remembered. Death comes only after the last person to remember her or him dies. By that measure, Joan of Arc is emphatically alive.