The Accidental Archivist

Things do not exist without being full of people.”

— BRUNO LATOUR, THE BERLIN KEY

WHEN I WAS A TEENAGER, my parents died a few years apart, and as I went through the rituals of laying them to rest, well-meaning people assured me that I would “always have the memories.” There were the memories, which I couldn’t seem to hold on to, and there was my parents’ stuff, which I could actually hold: a half-empty jar of moisturizer my mother used to soothe her radiation burns, new polo shirts that my dad bought but didn’t live long enough to wear, a Post-it note with a phone message on it—the last thing my father ever wrote.

Death turns everything into an heirloom.

Getting to know my parents better was no longer a possibility, but like an archaeologist, I could investigate their belongings for answers to questions I hadn’t thought to ask when they were around. Letters sent to my grandmother chronicle my dad’s adjustment to leaving home; a business card tells me about his first job out of school; a snapshot of a handful of scraggly perennials shows me the pride my mother took in the humble beginnings of the garden I knew so well. And like the curator of a tiny and very specific museum, I could comb the archives for whatever selection of items seemed most relevant to my station in life at the time. I took up running in college, and I trained wearing my mom’s jacket. I polished my shoes for my first office job with my dad’s shoe brush. I pried the backs off the picture frames and replaced photos from my childhood with pictures from my travels. I cut up my mother’s wedding dress for an art installation. Surely my parents would not have wanted me to feel bogged down by their possessions, but neither would they have wanted me to forfeit the comforts to be had in keeping them around.

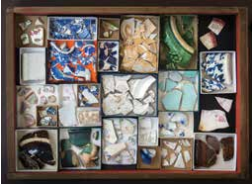

Image above from the series Garbagekammer (2016), a collection of the lost and discarded possessions of her house’s previous occupants unearthed from the backyard

At times, however, the sheer volume was overwhelming. My first apartment (not to mention a storage unit I rented) was full of the kinds of things no 21-year-old would own. My slowness to whittle it down felt like a character failing, an inability to part ways cleanly with the past or successfully integrate it into my present. But I was plagued with guilt, and sometimes regret, at parting with their things; there is a kind of emotional violence in detaching from the past after having been untethered from it by fiat.

Cultural expectations also fed into my dilemma. Despite the trendy infatuation with paring down one’s belongings to only those items that “spark joy” (per the internationally renowned Japanese organization guru Marie Kondo), certain strongly held beliefs persist about what should be kept in this scenario—“ good” china, a passport, a wedding gown, a valuable painting. Virtual strangers have expressed horror at the idea that I might do anything with these items other than store them indefinitely, compounding my fear that I might someday look around and realize I’ve done it all wrong. So I lived with, and paid to store, a motley collection of objects, which felt like too much stuff and also like never enough.

With each successive move through adulthood, I have managed to edit my permanent collection. I have a few regrets, like the dress I wore to my mother’s funeral, which she had taken me to buy several weeks before her death. I couldn’t bear to wear it again. But it was also the last thing she ever gave me. It sat untouched in the dry cleaner’s plastic for a few years, until finally I donated it to Goodwill, where it would be just another black dress with no clues to its provenance.

In the last few weeks of her life, when everything she told me took on an outsized importance in my mind, my mom explained that it was important to preserve bad memories along with the good ones. She might have wanted me to keep that dress. But like so many other things, I won’t ever know.

Just as grief is open-ended, so too is my relationship with all this stuff. I have come to embrace my roles as archaeologist and museum curator: their creative component, their imperative to make sense of objects with complicated histories. All this clutter—what the minimalism evangelists would have us throw out—offers new opportunities for connection with my parents, long after their perfumes and punch lines have faded.

A year ago my husband and I moved into our first home with a door wide enough to admit my parents’ kitchen table. The table is too large for the narrow room in which it sits. It’s bulky and awkward, but in its own way, it fits.

The work of artist Spencer Merolla is, as she states on her website, concerned with bereavement: “the material culture of mourning, and objects as repositories of memory which both retain and transmit meaning.”

Image above from the series Garbagekammer (2016), a collection of the lost and discarded possessions of her house’s previous occupants unearthed from the backyard