Fiction: Sanctuary

MY MOTHER LOVES THIS SHUL. She had met the rabbi at an upscale Book Luncheon and he had smiled at her comment on the book. My mom applied for membership in his congregation immediately. My dad picked a huge fight about the dues. Mom won.

“A brilliant man,” my mother says, of course. “He works with the kids in the congregation. And he is a civil rights leader. He has written several books. Anyone with a problem gets it solved by our rabbi.”

We live in Motown and the music is inside all of us here; the pulsing sound is everywhere. Flatbed trucks pull up to the candy store after school, the Marvelettes or the Supremes showing us white kids what it feels like to be “Dancing in the Street.” At the synagogue, the davening feels like Motown wrapped in a tallis. Especially from a boy named Isaac Crown, the thick-lipped, dark eyed, starter switch of my heart, and all body parts north and south.

The moan and swoop of the prayers from his mouth lift, escaping from ancestral closets full of must and decay. Of marrow. But, it’s not the words, or the sounds–it’s the way the boy moves that hooks me. Isaac’s prayers pound right in my belly, against my breasts and between my legs. If this is prayer, then God is good.

My mother smiles like she has a lollipop when she talks about the rabbi. Maybe he is responsible for keeping my parents living under the same roof. I know she and Rabbi meet all the time.

“Talk. We talk. He’s a smart man,” is all she ever says about him. Dad has stopped asking. She makes sure Rabbi sees her at the after-service blessing of the wine, the Kiddush. She’s on a first name basis with his wife.

“I can’t help feeling like we both go to shul to flirt with our impossible crushes,” I say to her.

“Rosie! Respect and schoolgirl crushes are not the same! Rabbi is a friend. He listens to me and hears what I have to say.” She looks at me with alarm, as if I wouldn’t understand wanting to be near someone smart and serious who never talks about money and only cares about what’s happening in your heart.

I look up at Isaac again. Smart and serious and davening with all his heart. We’ll go into the main service in a little while. My mother’s in there. Reading the prayer book. Checking out who wore their mink and who their gold jewelry, despite her best intentions.

When I first started coming to this synagogue on a regular basis, all I could see everywhere were the skinny faces of concentration camp survivors. The middle-class kids I am in Hebrew School with have aunts and uncles, cousins and parents, some of them, who were in the camps. Some dead and walking, some just dead. There are people in our synagogue with numbers on their arms.

My father brought home a magazine with a huge swastika on the front and in it are pictures of all those dead bodies, and the piles of teeth and the stacks of shoes and the smoke from the ovens. He has it in his office with his other war stuff.

NEXT TO ISAAC, in front of the service, is another boy, Ezra. I look at him and my eyes close. He is really skinny and has a huge nose, bony hands. In my brain Ezra is naked, too, and running, lifting his knees high, his scrotum bouncing, his eyes wild, his nose lost in mucus. His rear end is red and blotched as he moves away from me. He is crying, scared out of his mind, running from the Nazis and they are laughing at him. He is weeping and they are laughing and my stomach begins to turn.

I look back at Isaac, who is much better to think about without any clothes on.

“This concludes the Junior Congregation service for the week. Good Shabbes.”

Isaac has a deep speaking voice. His eyes parse the crowd and they catch mine. He almost smiles.

“Seats on the right side in front are reserved for Junior Congregation in the Main Sanctuary. Rabbi is just completing his sermon,” says Ezra, through his stuffed nose.

WE ARE WALKING ACROSS the lobby between the kid’s chapel and the large main sanctuary. It is airy and cold, with large sheets of plate glass that look out onto suburban tracts of tired snow. There are display cases with Jewish artifacts and museum lighting and a general feel of affluence and ease. This is what my dad’s dues pay for. Dad is not here. He’s working.

Isaac is moving across the lobby at the same pace that I am. We are in lock step and arrive at the large doors at the same time. He looks right at me.

“After you,” he says, and smiles.

“After me,” I say, and gag.

“Okay. After me.” He laughs and slips in ahead of me.

I manage to get through the door and pray that the coolness of the lobby keeps me from blushing. He’s waiting when I come through on my own steam.

At the interior doors of the sanctuary, he stops again and opens them.

“This time, you go first. I insist,” he says. He is courtly for a boy of seventeen.

We walk into the huge sanctuary together and side by side go down the aisle to the rows of seats open for us. I am trying to keep the soles of my feet hitting the floor with every step. The rows are filling up. There is one seat left at the end of the third row. Isaac pauses and then grabs my hand and steers me into the next row. He seats me in the seat next to him, and then releases my hand and gives me a prayer book. I manage to take it.

“I think they’ll start again on page 542.” He whispers this right in my ear. I actually do feel the bristle of his hair as he leans down and places his lips close to me.

“Oh.” Oh my my my my my. My heart is beating so loud. I am sure he can hear it. It is so loud I hear it. Over the loudspeakers. It’s a raspy rant of strain. It has words now and shrieks as well.

I feel Isaac’s body stiffen next to me. He lifts his head, his eyes, to the bima. Next to Rabbi is a young man in his twenties.

He has jumped up and is now grabbing Rabbi and shoving him away from the podium. I recognize the kid as the older brother of one of the girls in my confirmation class. He is known for being a nut case. He’s one of the “kids” my mother always talks about who get “help to solve their problems” from Rabbi. He doesn’t look happy today. He is out of focus and blurry. It’s his voice that screams.

“Hypocrisy!” it says. “Bullshit!”

His eyes are pouring out of his head, liquid red, already. In his hand is a gun. Shining metal grey. Isaac Crown’s hand grabs mine. I look at the Rabbi. He is motioning to the men in the back of the congregation to be still.

“Let the boy talk,” says the Rabbi.

The boy can’t talk, he can only open his mouth and huge black crows fly out. They flap around the heads of everyone there. They are shiny like the gun in the boy’s hand. A black crow swoops down and scrapes his claws against the Rabbi’s head, knocking his yarmulke, his head covering, to the carpet. There is blood where the crow’s talons have been.

Everything is happening in slow motion. From the back of the congregation, the old men rush forward, their prayer shawls stream behind them, huge wings. White bats, they flap closer and closer to the bima, they are about to tackle the boy but he turns the gun on the Rabbi. Blam! Blam! Like the Naked City, the boy points the gun at the Rabbi and the man falls.

“You should be ashamed!” screams the boy. And blam, blam, blam! The rabbi is dead.

Mr. Berry, the president of the congregation, flies toward the bima, a glider pilot on a mission, the hair in his ears electric. He flashes the battlefield. He stumbles on the carpet and wonders why there is no cover fire from his battalion.

The boy turns the gun on his own head and surrounded again by crows, he shoots three shots into his brain.

In front of us lie the bodies of the troubled boy and the dead Rabbi. It is so very quiet.

ISAAC CROWN HAS GRABBED my body and pulled me against him, burying his head in my neck. I can feel the bruise coming up on my belly, held so tightly against the wooden arm that separates the seats. Isaac is hyperventilating. His body is shaking.

I feel a warm wetness against my leg and then it drips onto my shoe. I look over and see a stain spreading against Isaac’s pants. His urine has a sweet smell. I close my eyes. I don’t want to see.

Isaac Crown lets go of my hand when he feels himself. Then, his eyes leak, too, and he gets up and stumbles past me, hoping for smoke. He stands like a criminal at the end of the row. He feels his damp socks and the rise of his nausea. He too flaps away.

MY MOTHER IS STILL IN her seat across the aisle. She starts to rise to run to the man dead in front of her but she is stopped by the streaking of Rabbi’s Wife, small, determined, industrious, to the family of the boy. Rabbi’s Wife holds them first. Comforts them. Touches their faces. She holds the space against any and all intruders.

Mama watches Rabbi’s Wife turn and move to the side stairway, spraying her territory. She sits on the floor next to him. She cradles what is left of his bloody head in her lap. The dark stain comes up on her blue suit, it covers her matching high heels and she kicks them off in a flash of a pique. She smooths whatever hair is left on his head over the oozing wound.

Rabbi’s Wife’s lifts her eyes. They are saucers of white heat. She has held the defeated pain of many survivors that she has counseled and brought back to life, but never has she felt this pain. She is a defeated angel. No angels are in the room with her. She is alone.

My mother is still at her seat. She watches the rabbi’s wife. How she spreads her tarpaulin of possession and entitlement around the dead bodies. Mama knows she cannot go and embrace the dead man. She cannot drop her tears on his body now. She must hold them secret.

I watch her slipping away from me into her grief. She sees me, and sinks back to her seat. Her shoulders fall from her ears, her head hangs cracked from her neck. She heaves her body to its side and lifts herself all in one move and rushes away, up the aisle.

As she goes, I see the rabbi’s wife look after her. Sending her away. Should she turn back, Rabbi’s Wife will curse her into a pillar of salt.

We walk to the curb. Watch as the blond ambulance drivers finally arrive and click open their gurneys. They silently part the crowd and move the stretchers into the lobby. Standing at the portico waiting for my dad to pick us up Mama’s hand darts at me. It melts into my arm. Her fingers hold the fabric of my coat.

“Rose. My hand. Hold it.”

I find her hand and put it in mine. I manage to bring it my lips. She looks up startled, wild. She coughs a word I do not understand.

My mother locks her knees in place and roots herself next to a crack in the concrete, companion to a cement pillar. She doesn’t lean; she just keeps her eyes wide, her head bent. I look down to see if she is looking at anything. There is dirty snow next to the curb, pocked with scattered pellets that are supposed to make it melt. I toe the gray mass with my leather boot. She squeezes my hand.

“Salt stains. Don’t,” she says. “Don’t.”

Susan Merson is a contributor to the anthologies Nice Jewish Girls and The Jew in America; her novels, Oh Good Now This and Dreaming in Daylight, are available on Amazon. She lives and works in the Hudson Valley.

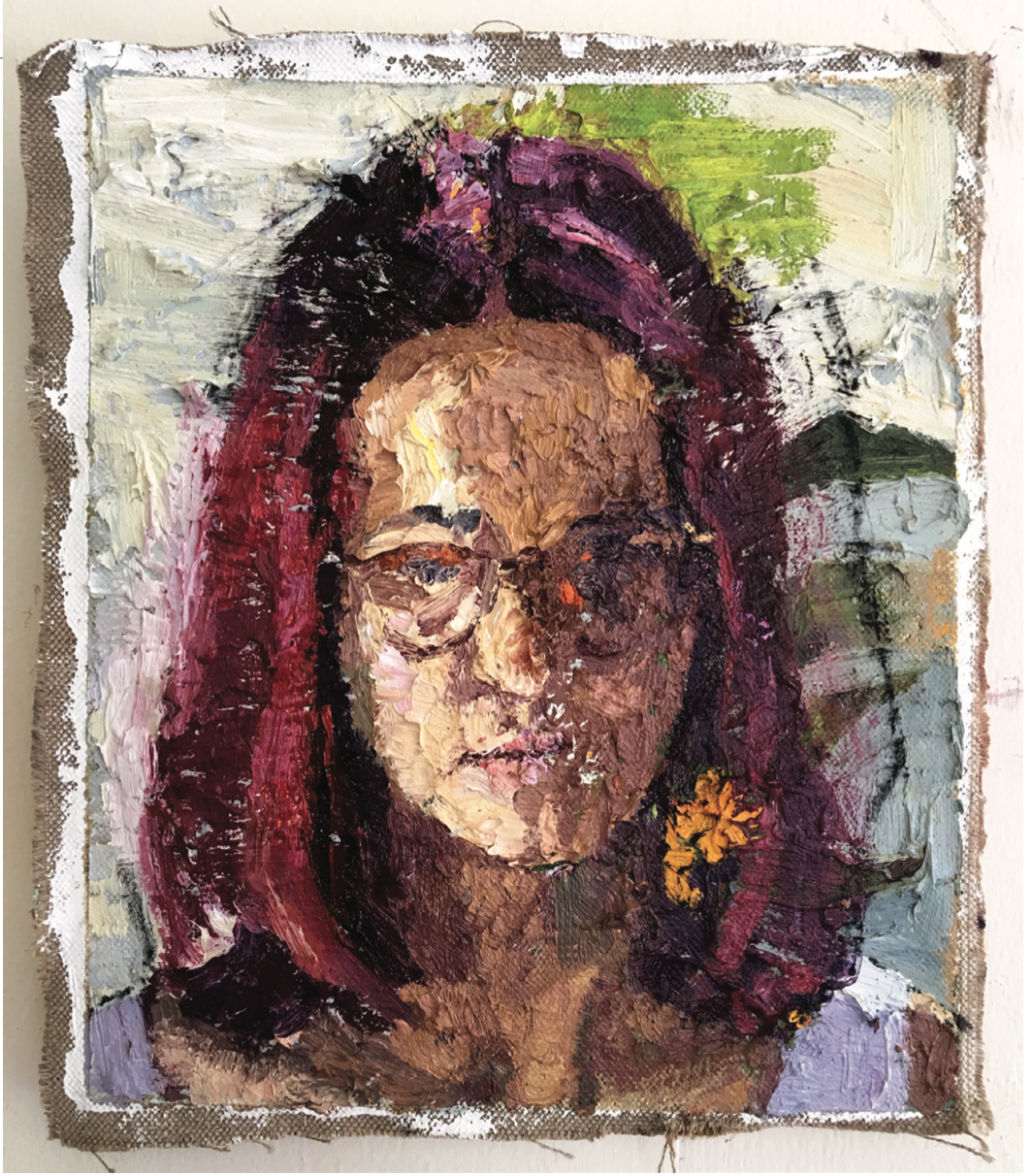

Art: “Petra on Her Last Day of School,” 2019, by Avital Burg