Peeling Back the Layers of Identity in Israel

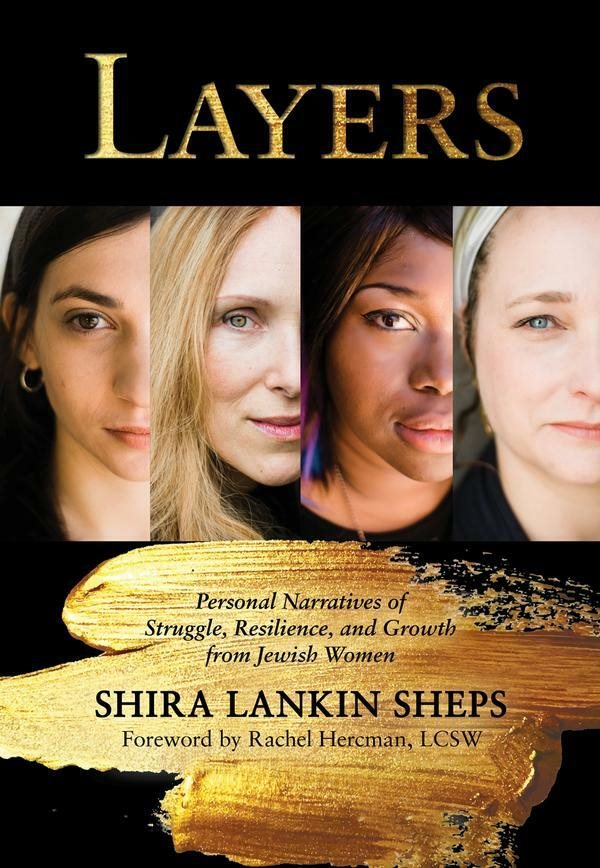

I read Layers by Shira Lankin Sheps (Toby Press, $39.95) over the course of a long summer Shabbat afternoon, putting down the book each time one of my kids called out for my help. At one point my daughter, who is still learning how to read in English, glanced at the cover while the book lay face down on the couch. “Ima,”she asked me, “Why are you reading a book about liars? Are all the women on the cover really liars, and what are they lying about?” I chuckled at the irony. “It’s not called Liars—it’s Layers,” I told her. “The book is a collection of true stories, without any lies. It’s about all the layers that make up a person when they really dig down to discover the truth about who they are.”

As I went on to explain to my daughter, each of the thirty-four chapters in Layers tells the story of another Jewish woman, most of them English-speaking immigrants to Israel. The chapters focus on the particular challenges and difficulties that each woman faced in her life, and how she managed—or is still managing—to overcome them and become a stronger person. Each woman is identified by first name and by the city in Israel where she currently resides. We meet Laura from Neve Daniel, who revisits the childhood trauma of the loss of her newborn twin sisters when she experiences a late miscarriage. Then there is Malka of Bayit VeGan, who uses a wheelchair on account of cerebral palsy yet nonetheless raises a family of six children with her beloved husband. Perhaps most impressive and extraordinary is Tamary from Naharia, a young mother of six who fights endless bureaucracy so as to bring her younger brother, who has Down Syndrome, to live with her own family in Israel after their mother becomes too ill to care for him back in the States. But each woman in this book is a warrior of sorts, whether battling infertility, cancer, disordered eating, depression, racial prejudice, etc. Though several of the women admit that their struggles are ongoing, each shares moments of resilience and resourcefulness, as well as insights gleaned along the road to recovery: “I find that healing often happens in a spiral,” says Kerry from Beit Shemesh, who was abandoned by her father at age fifteen. “You can revisit the same place, but hopefully, you will be at a higher point.”

The chapters in Layers are narrated in the first person, but as Sheps explains in her introduction, these are edited reworkings of her interviews with each woman she profiles. Each chapter is accompanied by several full-color photographs of the woman being profiled; the book had its origin as a photojournalism blog known as The Layers Project, in which Sheps interviewed and photographed Jewish women about taboo or stigmatized topics. Many of the photographs are quite arresting, capturing the subject’s inner beauty or shedding light on an aspect of her interiority. One particularly striking photograph, of a sepia-toned pomegranate cradled in a woman’s hands, resembles the head of a newborn—a fitting image for a chapter about a woman who loses her baby and decides to plant a tree in memoriam. Less compelling, unfortunately, is the written text; one would expect a higher quality of writing from edited interviews, and I cringed at the plethora of platitudes and cliches: “Honestly, life is too short to have regrets,” one chapter concludes, and then there is the woman who tells us, “One of my favorite Jewish quotes is, ‘This too shall pass.’” I found myself wondering whether a book was indeed the appropriate next format for The Layers Project, or whether perhaps the author might instead have created a podcast in which each woman speaks in her own voice without the pretense of editorial redaction.

The majority of the women profiled in Layers are religiously observant immigrants, and the book is full of italicized terms that would be familiar only to other observant Jews, or to other Israelis, and their inclusion lends the book an “insider” feel, as if it is written for other religious immigrants who are part of the same milieu as the book’s subjects. The author explains in the introduction that she wrote the book during her first year of Aliya and was limited by whom she was able to meet; still, it would have been interesting to hear from more secular women, more older women, and more women whose Zionism is nuanced and fraught. That said, each woman profiled in Layers is inspiring in her own right— “ordinary women who live their lives in extraordinary ways,” as Sheps introduces them. By reading the stories of their lives, we learn how we might more meaningfully live our own.

Ilana Kurshan is the author of If All The Seas Were Ink, winner of the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature