A Sephardi Family Saga

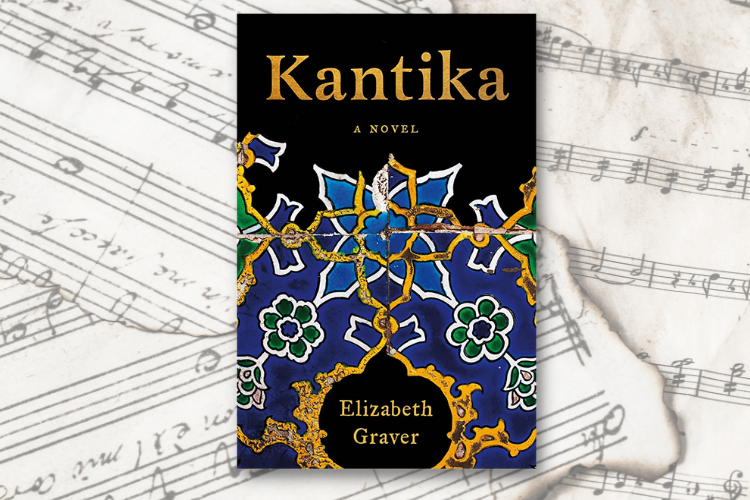

A new novel by Elizabeth Graver is always cause for celebration, but Kantika (Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Company, $27.99) is especially haberes buenos, one of her many Ladino speak- ing characters might say, as it brings new dimension to our understanding of the Jewish immigrant experience. Inspired by her maternal great-grandmother’s life, stories, and photographs, some of which are included in the novel, Graver has written “a duet between research and dreaming, history and imagination, my grandmother and myself.” Duet is le mot juste; “Kantika” means song in Ladino, or as Graver’s characters call it, Spanyol, the language of the Sephardic Jews, and music is a constant in this richly detailed family saga that covers almost fifty years and four countries.

Kantika begins in 1907 in Constantinople, a piece of her life that Rebecca Cohen Baruch Levy, the novel’s central character, will come to call this “the beautiful time.” Here, her family is wealthy and whole, cousins, aunts and uncles, and grandparents close by, all of them part of a vibrant Jewish community that mixes comfortably with its Christian and Muslim neighbors. This is “a time of wing- spans, leaps and open doors, of heedless, headlong flow from here to there…the world arriving not as lists or harkening back or future tense, but breath-filled music—kantar, sing.” Rebecca’s father plays the ney, a flute-like instrument, her mother sings lullabies, the street vendors sing out their wares in a variety of languages, and Rebecca sings at school and at play, and once as a little girl before the ark after services at synagogue. But even during this beautiful time, there are hints of ugliness. While the Greek Orthodox neighbors bring the Cohens gifts of colored eggs at Easter, Rebecca and her sib- lings are cautioned against going near the church that week or attending the Easter parade “with its rabbi effigy.”

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire and father Alberto’s financial woes require the Cohens to leave their beloved Turkey for Spain, where the prime minister has issued a decree that allows Sephardim to return and claim Spanish nationality. Of the family’s first move, Rebecca thinks, “What did place matter, even, if you kept the people together, but what she is only now coming to understand is that the move itself can change the people in a corrosive, internal rearrangement, not a collapse exactly—they are, she hopes, too tough for that—but a hardening, a shifting that fast becomes a kind of chronic misalignment.” Later, Rebecca’s oldest son will reflect that in America, “He is two boys, Dah-VEED and DAVE-id, the former at home in his skin, at home in Spain, the latter thick-jawed, stuttery and bent with nostalgia like an old man, stuck in fifth grade when he belongs in sixth.”

The Barcelona years are difficult, marked by the absence of song. Alberto’s ney gathers dust in his closet-sized office at the synagogue, where he is the caretaker. Rebecca’s younger siblings can’t attend school, since a baptismal certificate is required to enroll. And though the synagogue is unmarked, vandals throw bloody pig bones over its walled courtyard. When she accidentally reveals her faith, Rebecca is made to feel like “a beetle pinned to a board,” which beautifully conveys what it is like to be hated and feared and powerless. Rebecca is well aware that a “daughter of a Jew does not remain unmarried,” but her prospects are severely limited by the size of the Jewish population. This results in a disastrous first marriage to a fellow Turkish Jew, who repeatedly abandons her before dying young.

But if Kantika is about displacement, it is also about resilience. Graver begins the novel with the Ladino proverb “Let me enter, and I’ll make a place for myself.” In each place she lands, Rebecca creates a home, finds work, even thrives. She never encounters a problem she doesn’t want to fix or a situation that can’t be beautified. A second arranged marriage, this time to her childhood best-friend’s widower, Sam Levy, takes her to Havana and then to New York. Rebecca’s enterprising spirit allows her to take on a stepdaughter and her severe handicaps, despite resistance from Sam, his mother, and the girl, Luna, herself.

Rebecca’s singing becomes a critical component of Luna’s rehabilitation, and brings “Newmother” and Luna together. In this novel, song distracts and soothes, lifts spirits, binds past and present, and helps both singer and listener find their way home. Kantika, like the songs Rebecca sings, is full of sorrow and joy— and very beautiful.

Rachel Hall is author of Heirlooms (BkMk Press), selected by Marge Piercy for the G.S. Charat Shandra Fiction Prize.