Of Art and Stepmothers

In her latest novel, Take What You Need (Viking, $27), Idra Novey asks readers the question: “What’s a stepmother, anyhow”?

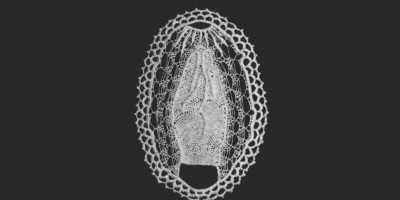

To answer this question, which one of her two protagonists paints on a sculpture she welded out of scrap metal and found objects, Novey alternates narration from Jean, the stepmother living in the Allegheny Mountains of Appalachia, and Leah, her grown stepdaughter. Though they’re estranged, Jean holds Leah dear.

Take What You Need begins after Jean’s death. Leah, her husband, and their child are on a road trip to Jean’s house, having been notified that Jean left Leah a collection of sculptures. The novel alternates not only between these two women, but also between two staggered timelines; Leah’s in the wake of Jean’s death; Jean’s a few years earlier, as she’s making the sculptures she calls “Manglements.”

Novey complicates the trope of the evil stepmother, with references to fairy tales suffusing the pages. Both women independently recall how Jean used to read fairy tales to a young Leah before bedtime. Even once Leah is a grown woman, she can’t help but think in fairy tales: when Leah and her young family arrive at Jean’s house, Leah almost seems surprised to find no “gingerbread roof.”

While numerous writers have penned retellings of canonical fairy tales, repositioning the villain as the hero, Novey offers no such simple transmutation of good and evil. Instead of switching the moral character of the evil stepmother and the innocent stepdaughter, she explores the complexities and multitudes within all of her characters. Set against the backdrop of a divided America at the end of Obama’s presidency, with chatter of his successor running for office in the background, everyone in this novel is morally implicated: the young men in Jean’s small town for their bigotry, and Leah, during her last visit to see Jean in Appalachia a few years before Jean’s death, for her own biases about the locals, some of whom, have the slightly off-kilter lives of people in fairytales.

Though Leah remembers Jean telling her “that the original Grimm fairy tales made no divide” between biological and other mothers, in the end the women sever the connective tissue they once expected to bind them together for life.

In Jean’s chapters we find her as a self-made artist, alone in the house she grew up in with only inspirational quotes from her heroes, artists Agnes Martin and Louise Bourgeois for company—and, for a while, her neighbor’s grown son, for whom she develops complicated feelings. Jean reflects, on reading one of her books about Louise Bourgeois: “Every night I sipped a few lines from her writings in bed. I had no nerve in the morning if I skipped my nightly Louise.”

In addition to asking readers to consider what’s a stepmother, the novel also asks, what is Art, and who is allowed to make it? While she nourishes herself with passages from Martin’s and Bourgeois’s writings, Jean can’t help but wonder: “what if deep down, where the art should be there was just a fearful homebody, just a nervous tinkerer?” A retired hospital clerk (her “tinkering” began only after retirement) and a lifelong art lover, her years-long subscription to Artforum was the subject of scorn from her dismissive Jewish ex-husband, Leah’s father.

Jewish references and themes lurk in the background. Jean’s own Jewish relatives own the junkyard where she gets her scrap metal—though now they live in Baltimore and manage the business from afar. And the Jewishness of Leah’s late mother’s family stays in the background too, maybe one of the under-the-surface bonds between the women.

Despite her loneliness, despite missing Leah, Jean sustains herself by creating a body of work: “It was the closest I’d known to contentment in years, watching the lowering sunlight refract off the cam- era lenses on the front of the capsules, their delightful spiral up the four metal sides. A contentment with oneself, Agnes wrote, that is success.”

Though Jean experiences creative pleasures, this quietly powerful novel leaves the reader with a final question: Is the act of making art itself enough, or is what an artist needs most of all a viewer, an audience, a witness? By engaging with this intimate fairy tale of stepmother and daughter, the reader is able to be that witness, even if the characters are fictional and Jean’s Manglements a figment of Novey’s marvelous imagination.

Rachel Zarrow is a writer in San Francisco.