The Secret Archivists of the Warsaw Ghetto

In a small museum on Tlomaskie Street, near the Vistula River, the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto tell their stories. A girl named Frania’s mother gives her a single zloty which she clutches as she wanders Leszno Street, deciding what food to buy. A nurse named Regina sells her dead brother’s clothes and her own underwear for money. A young woman named Eva, “stout and unattractive,” tutors other girls in English to keep herself housed and fed. A man called Dr. Gold oversees a disinfection brigade, trying to prevent the spread of typhus among the crowded buildings.

We know about Frania, Regina, Eva, Dr. Gold, and thousands of others because of the clandestine work of a group of archivists called Oneg Shabbat who, during World War 2, worked to keep the story of Warsaw’s Jews alive. Recording everything that happened in the Warsaw Ghetto from the time its gates were sealed, the archivists captured small details from tens of thousands of lives. In their small white notebooks, they collected newspapers and propaganda posters, records of underground schools, reviews of theatrical productions and literary competitions. They told us of the secret synagogues, the smuggling, the random executions, the imprisonments, and even, somehow, the stolen moments of joy.

When the great deportation to Treblinka began in 1942, the Oneg Shabbat archivists buried their notebooks in the ground, and in 1946, the three surviving members showed authorities where to dig up the treasure.

Today, the archive tell the world what had happened to the last of the Polish Jews in all their glorious, heartbreaking individuality.

I stumbled upon the Oneg Shabbat archive toward the end of a family trip to Poland in 2019 and decided that it would make for an interesting novel. As I grew immersed in novel-writing, I’ve let its people and stories live with me. But, in the terrible days since October 7, the people of the Warsaw Ghetto have become as present to me as my own family. Putting my daughter to bed, my mind wanders to the beautiful drawings Gela Sekstain made of her own young daughter, Margalit. Walking my dog, I see the fluffy white dog held, lovingly, by a group of men standing on a ghetto street.

Perhaps I’m holding tight to their stories to keep them alive in the face of this new onslaught of death. Or maybe I’m attempting, in my imagination, to rewrite their history—as the history that is currently being written is too fresh and too hideous to contemplate.

Once again, masses of victims are being tallied as numbers instead of names; once again, we do not know all the names of the dead, or we cannot find them all, or there are simply too many to list.

Besides, how do I conceive of 120 dead at a rave, 500 killed in a bombing, 2000 killed in two days? I am not equipped to do it. Human beings recognize other human beings, but we turn numbers into abstractions. It is easier to kill that way.

Still, in the face of this devastation, a new generation of archivists has rushed to meet the call, to keep the stories of the dead alive. They understand what the Oneg Shabbat archivists knew: that to retain some shred of dignity in the face of carnage, we must let the victims be seen in all their humanity. These archivists are the chroniclers of human legacy and loss, but instead of being forced to bury their stories in the ground, they are blasting them to us across our screens and into our homes, refusing to let us plead ignorance to what is happening in Israel and Gaza.

And so, in this way, we have learned of the Shaban family, parents and four children, crushed in their home in West Gaza. We have learned of Deborah Matias, an American-born Israeli, a music lover who died shielding her teenage son from a gunman’s bullets. We know that Saad Lubbab was a tiny Palestinian boy, young enough to be held in his mourners’ arms as lightly as a pillow. The Kutz family of five loved to play basketball together; when rescuers found their bodies, Aviv Kutz’s arms were still draped protectively around his children.

At night, when I’m walking my dog or putting my daughter to bed, I think of them too, and try to imagine what their lives were like, and try to remember.

When we turn human beings into pawns of a nightmarish geopolitical game, when we reduce their lives to sacrifice or slogan or excuse, we forget the lesson of every war that has come before this one. According to Jewish law, each of us was made in the image of God. To really contemplate what that means is to understand that it is our human duty to stop the killing. This is the lesson of the Oneg Shabbat archive that stands above all others.

Every single victim of this conflict was a person with tastes and preferences and habits, loved ones and ones who loved them. It is easy to imagine a little girl clutching a coin on the street; she belongs to history now.

We must do the much harder task of looking at each life lost today, and each person in jeopardy, with the same imagination, protectiveness, and awe.

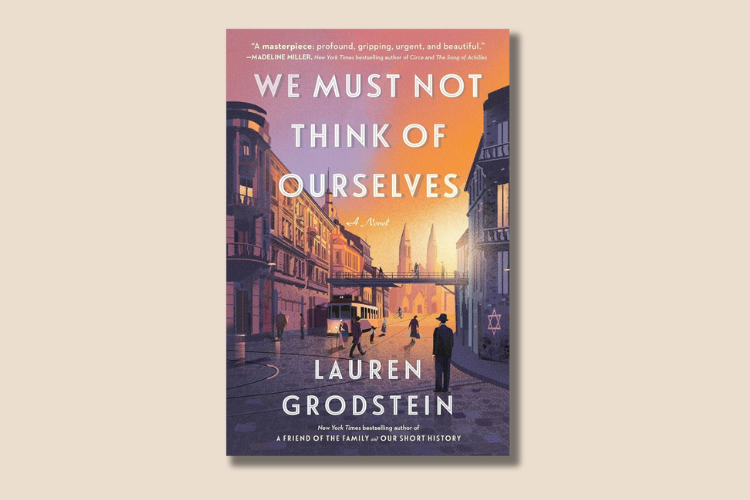

-Lauren Grodstein’s new novel is We Must Not Think of Ourselves, available on November 28. She is the author of Our Short History, The Washington Post Book of the Year The Explanation for Everything, and the New York Times-bestselling A Friend of the Family, among other works. She is a professor of English at Rutgers University-Camden, where she teaches in the MFA program in creative writing.