On Cormac McCarthy’s Jewish Heroine

Cormac McCarthy’s penultimate novel, The Passenger, follows a man named Bobby Western as he meanders and rambles from New Orleans to Tennessee to Europe and back, thinking equally about his brilliant sister and the end of mankind. In December, a slim companion text followed: Stella Maris, tracking conversations between Bobby’s sister, Alicia, and her psychiatrist during her final year of life leading up to her suicide (an event which opens The Passenger). “We first meet Bobby on the job,” John Jermiah Sullivan writes in his New York Times review. “His last name is Western because these novels are about the fate and impending destruction of the Western world.”

McCarthy is a difficult writer, but not a particularly subtle one.

Though Alicia’s touch is all over The Passenger, Stella Maris is entirely hers. She runs circles around her psychiatrist, but isn’t necessarily mean-spirited in doing so. She is, according to McCarthy, one of the most brilliant mathematical minds of all time–and thus there are precious few people who have ever walked the Earth capable of holding a real conversation with her about her fields of passion. She waxes poetic about quantum physics and the nature of God and Einstein and von Neumann and Gödel and her own hallucinations, always hanging around the periphery of her vision. She’s holed up, at her own insistence, in a facility in northern Wisconsin called Stella Maris (named after the sea-related honorific of the Virgin Mary). The book opens with her surprised by the Dr. Cohen that greets her, before quipping that there must be no shortage of Dr. Cohens out there.

Alicia has already decided that her suicide is inevitable, and as readers are encouraged to finish The Passenger before embarking on Stella Maris, there is little in the way of suspense. There is little in the way of plot, too, though this is not, in itself, a critical observation. Many of McCarthy’s books are more or less chronicles of people moving back and forth and back again. It’s all the metaphysical pressure swirling around them, conveyed and described in stark and dark dialogue, that has put so many of them in the very top tier of the American canon. That Bobby is working as a salvage diver at the opening of The Passenger is a tiny invitation to reflect on the overwhelming nature of McCarthy’s writing. You feel submerged. You have to let the words roll over you. Your eyes stop looking for the punctuation that isn’t there. You have to remember to breathe.

There are many reasons McCarthy might have chosen, in what he had to have known would prove to be his final published works, to explore (at length) his first true female protagonist, and his first Jewish ones. The specter of the Bomb hangs low and heavy over both books; Bobby and Alicia, we are told, are the children of a man who worked alongside Oppenheimer and spent their childhood in Los Alamos. Stella Maris consists solely of transcripts of psychotherapy sessions. Sullivan muses, “The Westerns made me think about the real-life McCarthys and see them in a different light, a useful one, in grappling with the writer’s oeuvre. I hadn’t thought before about how other he had grown up. Irish Catholics in the mid-South, for starters; clearly the Westerns’ Jewishness stands in for the McCarthys’ Catholicism.” But why bother with a stand-in to begin with? Halfway through Stella Maris, Dr. Cohen remarks that Alicia didn’t grow up Jewish, and she confirms. He presses: “But you knew you were Jewish” (McCarthy’s trademark lack of punctuation out in full force). “No. I knew something,” Alicia retorts. “Anyway, my forebears counting coppers out of clackdish are what have brought me to this station in life. Jews represent two percent of the population, and eighty percent of the mathematicians. If those numbers were even a little more skewed we’d be talking about a different species.”

In Vox’s review of both books, Constance Grady is more targeted than Sullivan: “Their surname is Western because that’s what they stand for: the western postwar world order, with all its prosperity and order and all its moral compromises.” It is in this light that assigning Jewishness to his characters starts to feel loaded.

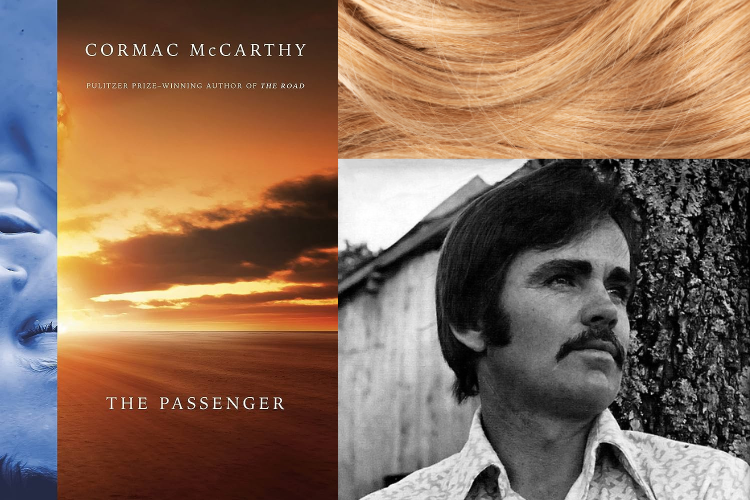

Renewed interest in Robert Oppenheimer with this past summer’s biopic certainly invited further conversations about Jewishness in the cataclysmic twentieth century. Bobby reflects in The Passenger that he owes his existence, in some way, to Hitler. “The forces of history which had ushered his troubled life into the tapestry were those of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, the sister events that sealed forever the fate of the West.” By the end of the novel, he’s living and working out of a lighthouse in Spain, learning to pray the rosary and searching for quiet gnosticism. Similarly, Alicia closes Stella Maris by outlining her desire to become a “kind of Eucharist” in the suicide she fantasizes about. We are told, over and over again, that Alicia is golden-haired, beautiful beyond measure, a real knockout. She is hopelessly in love with her brother, and he with her. They are All-American–most especially because they were born because of and into a cradle of violence. Most of his canon strains under the weight of heavy Catholic-Christian allegory, and both The Passenger and Stella Maris are no exception.

That McCarthy, then, would toss in a gesture toward Jewishness in a book so overwhelmingly Catholic at first glance is a puzzle that yields different conclusions at every turn. Maybe he believed (or knew), as Abe Greenwald posits for Commentary, that most mathematical geniuses happened to be Jewish, and wanted to show he’d done his homework. Perhaps McCarthy felt Jewishness was appropriate to bestow upon the Westerns because of what Jews know (as a cultural matter? As a spiritual one?) about the mind. There are, of course, the tropes of Jewish involvement in psychiatry–but the flip side of our interest in the field is our stake in it. Jews do not have statistically significantly higher rates of mental illness overall compared to the general population, though perhaps only because “neuroticism” no longer has a listing in the DSM. Alicia knows very little about Jewish practice, but believes that Jewishness can be inherited, can run through her veins and leave a mark that others will see when she encounters them. Some kind of epigenetic cosmic clap of the universe conspired to seal her fate, long before she came into being.

Abe Greenwald, again, hypothesizes that the key to understanding the relationship between Bobby and Alicia is found in Stella Maris, particularly in one exchange: “Can a thing exist with no assistance?” “Logically no,” she responds. “If space contained but a single entity the entity would not be there. There would be nothing for it to be there to.”

Interpreting, Greenwald writes: “It’s an odd formulation, ‘to be there to,’… but the two books are there to each other, each the thing that means the other exists.” The books rely on each other, exist because of each other, as do Bobby and Alicia—and perhaps, if we’re swinging for the fences here, as Jewishness and the rest of the Western world do.

Certainly there would be no Christianity without the word supposedly made flesh in those ancient Jews who didn’t believe, at least not in the beginning, that they were abandoning their Jewishness, abandoning what had marked them as different since God told them to mark themselves. They were built from the same materials, and then they cleaved apart. Bobby and Alicia, too, are built from the same materials, circling each other, knowing that if they touch each other the way they really want to, they’ll set off a cataclysmic reaction not unlike the fission that drives an atomic bomb. When Alicia is asked what she told Bobby while he lay in a coma following an accident, she says: I would rather be dead with him than alive without him. There would be nothing for it to be there to.

In the end (or in the beginning, depending on which book you read first), Alicia takes her life on a snowy Christmas morning, tying a red sash around her waist so she can be spotted in the blinding white landscape before hanging herself from a completely bare tree. The unnamed hunter who stumbles across her body immediately thinks to kneel, and McCarthy notes that the outward turn of her hands resemble certain ecumenical statues whose attitude asks that their history be considered. That the deep foundation of the world be considered where it is its being in the sorrow of her creatures. Even in death, Alicia Western is frozen into the shape of a disciple, carrying the whole of creation on her back.