Photo Credot: Thomas Vogel on Unsplash

Those Long-Ago Crushes on Jewish Actors Playing “The Other”

Not long ago, an elderly actor named Ed Ames died, and even though Ames was white, as I am, I mourned him as the object of my first interracial crush. I was eight in 1964, when Ames appeared on the hit television show Daniel Boone, playing Mingo, the Oxford-educated son of a British earl and a Cherokee mother. I had no idea the actor playing Mingo wasn’t really Native American (if I had known, it wouldn’t have struck me as offensive, so widespread was the practice back then). All I knew was Mingo was darkly handsome, usually wore no shirt, and was smarter and more eloquent than any other character on TV. I suspected I was meant to have a crush on Fess Parker, the brawny all-American actor who played the heroic white pioneer Daniel Boone. I liked Daniel, and I included him in all the fantasies in which I rescued him and Mingo, only to be injured by the bullet or arrow meant for them.

But it was Mingo’s tender kiss I imagined as my reward.

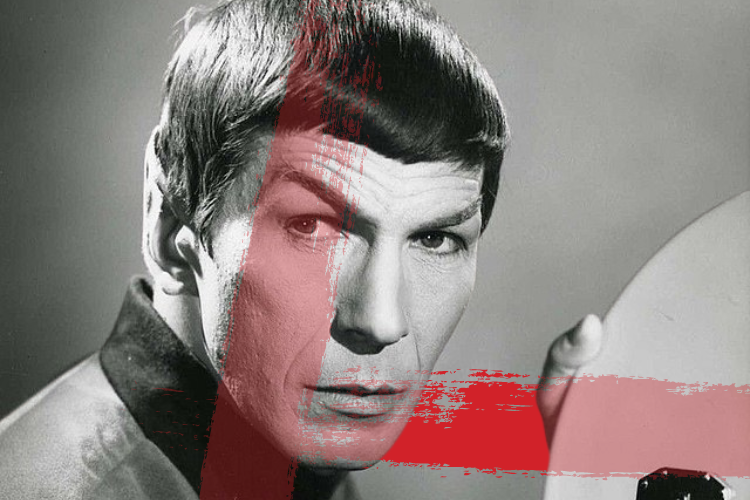

When Star Trek hit the airwaves a few years later, I finally gave up my dream of winning Mingo. Mr. Spock was my new obsession. I longed to convince the chief science officer of the Starship Enterprise that, unlike other female earthlings, I was worthy of his love.

What would be the triumph in winning a kiss from Captain Kirk, who seemed willing to bestow his favors on any female, human or extraterrestrial? I dreamed of coming up with an obscure scientific principle that eluded even Spock, saving all of us from catastrophe. Spock would raise one pointy eyebrow to indicate his admiration for how logical and brave I was, then take me in his arms and kiss me (fortuitously, this romance took place during Amok Time, when Vulcans are overtaken by an irresistible drive to mate or die).

I knew that a nice white Jewish girl wasn’t supposed to be obsessed with these kinds of characters: the sidekick, the Other, the Vulcan or Native American. But I had never been one to follow the rules a nice white Jewish girl was meant to follow. So imagine my surprise when I learned Ed Ames had been born Edmund Dantes Urick, the son of Jewish immigrants! I wasn’t exactly shocked to discover that Leonard Nimoy, the actor who played Spock, wasn’t Vulcan. But I was startled by the revelation that Nimoy was a Yiddish-speaking Jew (like Ames—and three of my grandparents—Nimoy’s parents immigrated from what is now Ukraine) and that the live-long-and-prosper-sign I had been so proud to master had been inspired by a Jewish blessing.

My inability to recognize either actor as Jewish isn’t surprising. The Goldbergs, a warm-hearted situation comedy about a working-class Jewish family, was a hit in the 1950s, but American sitcoms went all-Christian and all-white after that. Even in the 1990s, when Seinfeld and Friends swept America, George, Elaine, and Kramer were played as gentiles, while Ross, Monica, and Rachel’s religious affiliation was rarely referenced.

What puzzles me is why I should have been so attracted, at such a young age, to men I had no choice but to read as non-Jewish, nonwhite, and, in Spock’s case, nonhuman. Virtually none of the Jews I knew growing up in the Catskills were dark-complected; few were all that eloquent, rational, or intellectual. And yet, I must have picked up from my parents that even as I might want to learn to throw a tomahawk or pinch a nerve to subdue an enemy, brains and eloquence were far more effective weapons. I knew enough about the Holocaust that I would have counted myself on the side of anyone who wasn’t Christian or white, anyone whose pointy ears meant they didn’t fit in with other members of the crew. (That William Shatner also is Jewish complicates this interpretation. But anyone watching Star Trek would have read Captain James T. Kirk as the quintessential military hero, cocky, confident, the heroic Christian ace.) Even in a town with an unusually large Jewish population, I could sense I didn’t resemble the characters I saw in movies and on TV, and so I developed crushes on men who seemed exotic, the irony being that those characters were played by Jews.

Many of us are attracted to those who seem familiar. Others can’t help but fall in love with people they have been taught to regard as alien, even dangerous. Though I have dated across the racial and religious spectrum, my serious romances have been with people who, like Mingo and Spock, combine both sets of qualities. I married a Texan who was tall and dark, with the angular features of his paternal Jewish ancestors, a highly rational scientist whose Christian mother boasted ancestors who had come over on the Mayflower and who raised her son to be Unitarian. My wedding photos are hilarious: as we dance the first dance, my reedy-thin Jewish mother stretches to reach the shoulders of my hulking, six-foot-four father-in-law, while my five-foot-six father cranes to meet the gaze of my six-foot-tall gentile mother-in-law, whose platinum-blonde beehive adds another six inches to her height. Less hilarious were her derogatory remarks about Jews, Blacks, and Mexicans or her horrified reaction to our announcement that we would be raising her only grandchild as a Jew.

If someone specifies on a dating site that they prefer to meet only those of their own background, should you swipe left because they’re racist? If they express a preference for a race or nationality not their own, are they being broad-minded … or fetishistic?

After my divorce, I spent years in a relationship with a Polish Catholic man whose olive complexion, straight black hair, and almond eyes meant he often was mistaken for Native American, Asian American, or Mexican American. His father blamed everything wrong in Poland on the Jews, yet Marian knew more about Jewish history than I did and was infatuated with all things Jewish. Touring Warsaw and Krakow, I grew so anxious I barely could breathe, yet the language and food felt oddly comforting. After we broke up, I found myself dating a kind Midwestern intellectual whose stepfather was, if not a literal Nazi, then a Nazi sympathizer. My boyfriend’s ex-wife had been a Jew, like me.

Even as recent social movements mean many of us have intensified our pride in our identities, more of us are also marrying and having children in ways that, in the long run, might blur those same identities, perhaps beyond recognition. And yet, we rarely discuss the ironies or erotics of falling in love with, having sex with, or marrying someone who doesn’t share our religion, race, or nationality. If someone specifies on a dating site that they prefer to meet only those of their own background, should you swipe left because they’re racist? If they express a preference for a race or nationality not their own, are they being broad-minded … or fetishistic? What about a person who belongs to a historically marginalized group and prefers not to date someone who belongs to a group that traditionally has oppressed them? What do you owe a parent who expects you to marry within your faith? Is attending Christmas mass with a partner equivalent to lighting candles on a menorah? Do you find yourself drawn to potential partners who remind you of your brother or your mother, or does such a resemblance incite you to flee screaming in the opposite direction? A few movies, plays, and television shows, such as the recently released You People, explore tensions and contradictions such as these. But the conflicts usually are treated in a superficial way and played for cringey laughs.

Many of us find it too risky to tell the truth about falling in love with someone our parents or grandparents consider taboo. I tend to be fearless in what I write, but even I am afraid to hurt the people I love, or used to love, or might someday fall in love with. And I still find myself knotted in my own contradictions. I adore my Pakistani daughter-in-law and am thrilled that she and my son are raising a family together. I glory in how many races, religions, and nationalities my grandchildren will be able to claim as their own. I hope that by whatever star date the Starship Enterprise truly sets sail, the crew will have so many fragments of each other’s DNA coursing through their veins that their understanding of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, and sexuality will have evolved to be truly enlightened. And yet, given how much I value my own people’s history, culture, and theology, I can’t help but feel sad that none of my descendants will be Jewish.

_

Eileen Pollack is a former director of the MFA Program at the University of Michigan and, most recently, the author of Maybe It’s Me: On Being the Wrong Kind of Woman.