Brian Morton’s Memoir of His Complex Mother

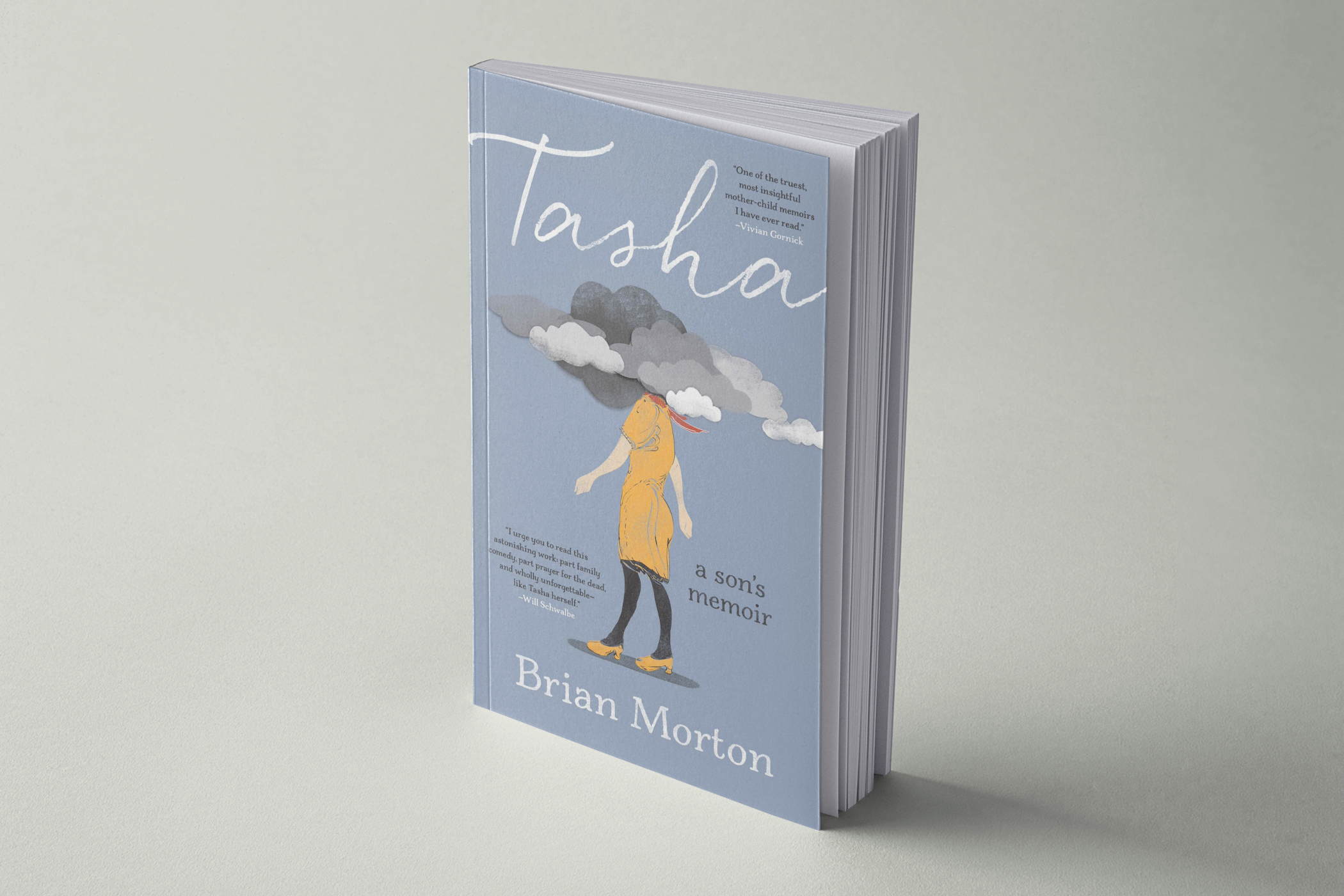

Tasha Morton was a force of nature: a brilliant educator who left her mark on generations of students—and also a whirlwind of a mother, intrusive, chaotic, oppressively devoted, and irrepressible. For decades, her son, the novelist Brian Morton, kept her at a self-protective distance, but when her health began to fail, he knew it was time to assume responsibility for her care. Even so, he was not prepared for what awaited him. He charts her inexorable decline in Tasha (Avid Reader Press, $28), a piercing memoir that though sober and often dark is nevertheless shot through with lightning-like bursts of humor. He talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about his effort to capture this mercurial, contradictory woman on the page.

YZM: Why do you think it’s so important for us to try to see our mothers in all their full complexity, not just as mothers, but as women in their own right?

BM: I think it’s important for all of us to see one another in our full complexity. But yes, in the book I was thinking about mothers—and, in particular, about mothers and sons. It seems to me that men tend to be much more aware of what we owe to our fathers, how we resemble our fathers, how we’re different from our fathers, and so on. We’re less aware of what we owe to our mothers. I think men would be better people if we did more to acknowledge the complexity and depth of our relationships to our mothers, and the full extent of how much we resemble them. I think the world would be less fucked up.

YZM: Your mother sounds like a quintessential Jewish woman in some ways, and a real rebel in others.

BM: That was one of her many contradictions. She left home when she was sixteen; a few years later, she went to live in Israel for a while just after the War of Independence/Nakba. She and my father were members of the Communist party into the early 1950s; they weathered some tough years together after the labor union he worked for was kicked out of the CIO for its politics. So you’d think she was someone who understood that taking risks is part of the growth process—part of life. But this was not an idea she wanted to pass on to her children. It was almost like she wanted us to be terrified of everything. Even when I was in my fifties, if she read about somebody who’d choked on a spoonful of peanut butter, she’d call me up in a panic at 11 pm to tell me to be sure to eat my peanut butter on a slice of bread. It makes me smile to remember it, but it sometimes made me crazy to experience it.

YZM: I loved the line, Maybe all she needed…in order to be at her best, was someone to annoy her, affectionately, for the entire day. Care to elaborate?

BM: Even when her dementia and her depression were at their deepest points, you could usually reach her by joking around—teasing her, or finding some way to provoke her into retorting with a witty insult. Even after she lost her grip on most things—when she wasn’t sure whether she was still living in her house or not, or whether her parents were still alive—the one thing she never lost was her sense of humor. It remained a way to connect with her when everything else was gone. Which was a comfort.

YZM: Here’s a line that I feel could characterize Tasha: Old, frail, disoriented, she nevertheless retained an unbendable intensity of sheer will, trained on the one clear goal of living her own life. Can you say more about this?

BM: She was someone who never let others tell her what she could or couldn’t do. This was breathtakingly admirable—and, near the end of her life, when she could no longer take care of herself, it was also breathtakingly frustrating. In so many ways, big and small, my sister and my wife and I tried to make her life a little easier, and time and again she fought us tooth and nail.

But maybe this isn’t so unusual. Maybe everyone who’s had to take away an elderly parent’s car keys—for one example—has stories similar to mine.

YZM: You write about the importance of community—and its lack—at the end of life. What are your thoughts about the way we as a society care for our elderly versus our own needs?

BM: I don’t think we as a society are good at caring for anybody. With a few exceptions, such as the bursts of legislation in the 1930s and 1960s that brought us Social Security, unemployment insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and so on, our national motto seems to be “You’re On Your Own.” But I think we’re especially bad at caring for the elderly. When my mother was suffering from dementia during the last years of her life, I was stunned at how few resources there were. Figuring out what Medicare would and wouldn’t pay for; finding help for her in her home; finding a dementia facility that would treat her carefully and respectfully—apart from a few helpful books, such as Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal and Jane Gross’s A Bittersweet Season, we felt like we were groping our way through the dark. And we were among the lucky ones. She had enough savings to afford a dementia facility that wasn’t absolutely horrible; my sister and my wife and I had the sort of cultural capital required to look for adequate resources and to loudly insist on good medical care. But the point is that we felt like we were on our own, and it’s madness that we’ve got a significant social problem in this country—more and more people living long lives and in need of serious care at the end—and every family is forced to try to solve it on their own.

We have universal schooling for the young; why can’t we have universal programs for the old? Programs that make sure old people have the social supports to live out their lives with as much dignity and comfort as possible? As we learned during the pandemic, when temporary relief programs lifted millions of people above the poverty line, poverty in America is a political choice. The scandal of elder care is a political choice too.

YZM: Sometimes I think that parts of our souls are sheared off and left behind in the places that have caused us pain. What were those places for Tasha?

BM: When I wrote that line, I was thinking of a little bridge over the Hackensack River where she got stuck in a flood during a thunderstorm when she was 85. Her car died; the water made its way up to her knees; she didn’t have a cell phone; it was late at night; she was sure she was about to die. Finally police officers in a patrol car found her and saved her life, but it was the most terrifying few hours she’d ever lived through, and she suffered a stroke that night, or just afterward, and she was never the same after that. I would sometimes drive her past that spot—it was unavoidable; it was on the way to her doctor’s—and every time we’d pass it, it was like a little shiver went through her.

YZM: Your mother’s last words to you were harsh, even lacerating. How were you able to put them in some kind of perspective or context?

BM: My mother’s last words to me, after I told her I loved her, were “I hate you.” Those were the last words she spoke to anyone. It was when she was, as one nurse put it, “actively dying.” She’d been almost completely unresponsive for days—her eyes closed, her lips sealed tight. It had been days since she’d even been able to swallow any liquid. I’m not sure she knew who she was speaking to. But I kind of hope she did. To me there’s something strangely glorious about the idea of someone like her—someone who’d conceived of herself as willing to sacrifice everything for her children—ending her life with those words.

Earlier you asked about seeing our mothers in all their complexity, not just as mothers, but as women in their own right. It felt as if my mother, at the end of her life, was making a demand to be known in her full complexity. Almost as if she were saying, “You think you know me? You want to think of me as just your loving mother? Think again!” And maybe she wasn’t just speaking to me. In the book I try to imagine everything that might, just possibly, have been going on in her mind. For whatever reasons (because she’d been a Depression baby? because she’d had a charismatic but unavailable father?), she always felt she wasn’t getting enough. She always felt the people she loved weren’t giving her enough. I imagined that with those last words she was expressing not only her disappointments with me, but her disappointments with my sister, and my father, and her parents—with everyone who hadn’t given her everything they could have. And maybe expressing her sheer rage at life, which never gives enough to anyone.

YZM: At the end of the book, you express some ambivalence about the portrait of you’ve painted of your mother; do you feel a sense of satisfaction for at least having tried?

BM: Yes, I do. If I could speak to her, that’s what I’d say. I’m still not sure, even after writing all these words about you, that I was able to see you as you were. But I tried.