How Mary Lumpkin Liberated the South’s Most Notorious Slave Jail

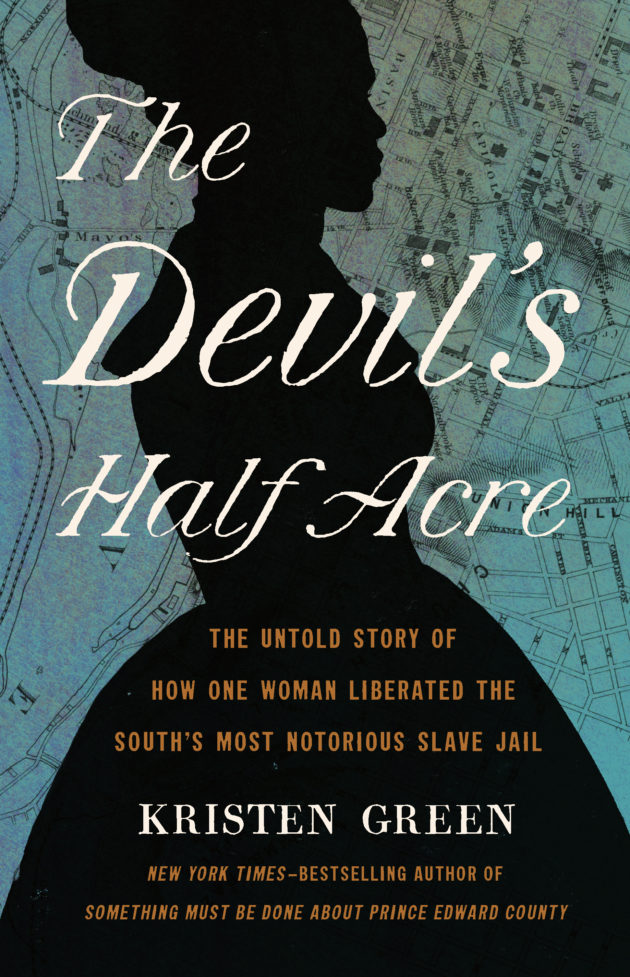

Just in time for Passover, Lilith is proud to present the liberation story of contributor Carolivia Herron’s foremother, who was born into, and escaped, bondage. With an introduction from Herron, the following is an excerpt from “The Devil’s Half Acre: The Untold Story of How One Woman Liberated the South’s Most Notorious Slave Jail” by Kristen Green.

A book about one of my ancestors just came out. Her name is Mary Lumpkin. When she was 8 years old, she was given to a white man, Robert Lumpkin. She gave birth to their first baby at just 13 and went on to have five surviving children, seven in all. I’m a descendant of the youngest child.

These are parts of stories that I pieced together all of my life. We have only put it all together in the last year. People in Richmond have been trying to find the descendants of Mary Lumpkin because she survived him, took his money that he used trading slaves and helped found Virginia Union University for formerly enslaved Black people. I mean, can you imagine? Somebody enslaved at birth and raped at eight years old was able to resist so much that, at 35 or 36, she was was still able to take what good she had to help formerly enslaved people. I had no idea that there could be that kind of resilience in anyone. No novel I come up with can be as impressive as that.

Thank you, my dear Great Great Grandmother Mary Lumpkin. You are Miriam for us, dancing with the timbrel, I hear you from the freedom side of the sea.

Here at Pesach, I add Mary Ann Lumpkin, my enslaved African American ancestor to the name of my imagined Egyptian ancestor, refusing enslavement, setting off toward freedom—and sending her children toward freedom and wisdom. Paraphrasing John Milton, “They also serve who stand and point and guide and show the way.” Thank you, my dear Great Great Grandmother Mary Lumpkin. You are Miriam for us, dancing with the timbrel, I hear you from the freedom side of the sea.

– Carolivia Herron

Before she knew Mary Lumpkin’s name, Carolivia Herron had long heard of her great-great-grandmother’s efforts to protect her children. When Herron was nine and pretending to sleep on the rug in her grand- mother’s parlor in Washington, DC, an aunt came in with friends and shared details about their enslaved ancestor.

Herron remembered her aunt recounting that the ancestor had demanded money of her enslaver for the enslaved children she had been forced to bear. “My unnamed female ancestor had managed to get power over him,” Herron said.

She recalled her aunt’s descriptions of the enslaver’s cruelty and that his job assisted enslavers. Herron also knew that her ancestor had freed her children to three states—Louisiana, Ohio, and Massachusetts. Later, an uncle made another revelation: “We changed our name,” he once said to her. He told Herron that her great-great-grandmother’s name was Mary, which he learned from his grandfather, George W. Lumpkins—presumably Mary’s son who had changed his first name and added an “s” to his last name.

“Our family has been known for strong women and that falls right into place,” she said.

Herron’s mother, Georgia Johnson Herron, a longtime Washington, DC, public school teacher, said it makes sense for her to be descended from a woman like Mary Lumpkin. “Our family has been known for strong women and that falls right into place,” she said.

When I tracked down other descendants—great-great-grandchildren and great-great-great-grandchildren—they did not know any of Mary Lumpkin’s story. She had been completely forgotten. Her name, her race, her background as an enslaved woman—all gone. Her role as the mother of her enslaver’s children—lost. For generations, this branch of the family tree has lived as white, oblivious to her past and its important place in American history. They did not know Robert Lumpkin’s legacy as a slave trader either.

Martha Kelsey’s children had passed as white and married spouses identified as white by government officials. They had lived in white neighborhoods, setting the stage for subsequent generations to continue passing. In so doing, Martha Kelsey’s children were attempting to use whiteness to fit into a world that valued white lives above others. In the aftermath of the Civil War, when white people were angry about Black men and women’s freedom, there were lots of reasons a Black person would want to pass as white, the most important of which was not having to worry about being harassed or killed.

The Lumpkin children apparently were divided in how they wanted, or were able, to racially identify. Herron has a photo of George W. Lumpkins, who was dark-skinned with light eyes, and she noted he could not have passed. He married a light-skinned woman, Rowena Nelson. Also born enslaved in Richmond, she was likely the child or grandchild of a white enslaver who was sent to Massachusetts to be freed and protected by the Wampanoag people. The couple married around 1875 and lived in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, with the Wampanoags, and Rowena didn’t know until later in life that she was Black. She was so disgusted by white people’s treatment of Black Americans she vowed to “make her descendants Black,” Herron said.

When the family moved to Washington, DC, Rowena Nelson Lumpkins “rejected the inclination to pass as white vigorously,” Herron said. When her daughter Lucy had three suitors, her mother forced her to marry the darkest one. Herron has a saying about how her great-grand- mother’s decision to live as Black impacted the family line: “White to Black in three generations.”

But other descendants who lived as white probably stopped talking about Mary Lumpkin so long ago that none of her descendants alive today ever had a chance to know her story. Countless families who passed as white after slavery are not aware of their Black ancestors. Yet as DNA testing has become more popular through genealogy websites, a number of Americans who believed they were white have learned otherwise. Some 4 percent of white US residents have at least 1 percent or more African ancestry, which indicates they had a Black ancestor within the last six generations, 23andMe scientist Kasia Bryc found. Based on those numbers, as of the 2010 census, some 7.8 million Americans who identified as white would have been classified as Black according to “one drop” rules.

When I reached out to some of Mary Lumpkin’s descendants who live as white, they seemed truly surprised to learn of their connection and were pained to hear of the trauma she had endured as an enslaved woman. Several told me they wished her legacy had not been kept from them. For generations, the history of trauma and enslavement has been hidden in their DNA.

That Martha Kelsey’s family’s telling of its history made no mention of Mary Lumpkin or her children being Black or enslaved speaks to the structural racism at the heart of America. One descendant said that she was told that the family was descended from a white indentured servant. Another descendant noticed that a space next to George Kelsey’s name was blank where Martha Kelsey’s should have been. “We’re not supposed to talk about this,” she was told by her mother. “Your great- great-grandfather married an Indian woman. He was ostracized from the family.”

Martha Kelsey’s name and race were kept secret from subsequent generations even after her racial identity became more palatable to most Americans. By making her an indentured servant, she became white. By turning her into an Indigenous person, the family had acknowledged this country’s aversion to Blackness and engaged in the historical practice of using an Indigenous background to erase Blackness.

But claiming that Martha Kelsey was Indigenous, and presumably descended from an Indigenous mother, may have been a story her descendants told in order to hide that they were Black.

Perhaps Mary Lumpkin was indeed part Indigenous. After all, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people were enslaved in America. George W. Lumpkin connected with, and was accepted by, Indigenous people in Massachusetts who may have protected him when he escaped slavery, Herron said. But claiming that Martha Kelsey was Indigenous, and presumably descended from an Indigenous mother, may have been a story her descendants told in order to hide that they were Black.

Over time, through marriage to white spouses, some or all of Martha Kelsey’s descendants easily passed for white and accepted its inherent privileges. A potent mix of shame and racism may have kept descendants from acknowledging her and her mother at that time—and from acknowledging their slave trader ancestor too. Instead, false narratives were concocted and passed down to generations of unsuspecting offspring, many of whom might never have known their true roots if I had not called. And yet they may have carried the unexplained pain of not knowing exactly who they are.

Deciding to hide or ignore our pasts—and not share them with our offspring—is one of many ways in which Americans have refused to acknowledge this country’s violent history of enslavement. Many of us are descended from enslaved people, from enslavers, or both. This history still lives with us and reverberates today.

Whether Mary Lumpkin’s descendants know it or not, the violence perpetrated by their ancestor Robert Lumpkin is woven into their lives, as is the trauma that Mary Lumpkin endured. The resilience she demonstrated and the joy she surely experienced, despite the terrible conditions of her enslavement, are also part of their constitution.

“I’ve come. I’ve returned,” she whispered into the grass, speaking to her ancestors. “I was able to survive, and you won’t be forgotten. I will hold you up. I hope you can have peace.”

As a scholar of Black history, Carolivia Herron learned about Lumpkin’s Jail years ago but for a long time was not aware of its role in her life. When she gave a talk in Richmond in 2014, she visited the site for the first time and connected the dots. This Mary Lumpkin was the “Mary” she had been told about—the one who demanded money from her husband and freed her children. After realizing what her kin had endured at the slave jail, Herron walked into the middle of the adjacent African burial ground and fell to the ground, overwhelmed by grief.

“I’ve come. I’ve returned,” she whispered into the grass, speaking to her ancestors. “I was able to survive, and you won’t be forgotten. I will hold you up. I hope you can have peace.”

Though she did not grow up with all the facts about her ancestors, visiting the site cemented her connection to the history. “This was my family,” she said. “I belong here.”

Adapted excerpt from The Devil’s Half Acre: The Untold Story of How One Woman Liberated the South’s Most Notorious Slave Jail by Kristen Green. Copyright © 2022. Available from Seal Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.