A Moving Fictional Account of the Spanish Civil War

When Mills College Spanish professor Judith Berlowitz retired in 2008, she was already what she calls “an obsessive genealogist.” Her exploration of family history had revealed a host of intriguing connections, among them, that Robert Oppenheimer, the “father” of the atomic bomb, was a fourth cousin. She also learned about another distant relative, Klara Philipsborn, a German-born Jewish communist who moved to Spain in 1930 and became involved in the Fifth Regiment of People’s Militias, an anti-fascist mobilization to defeat General Francisco Franco’s takeover of the country.

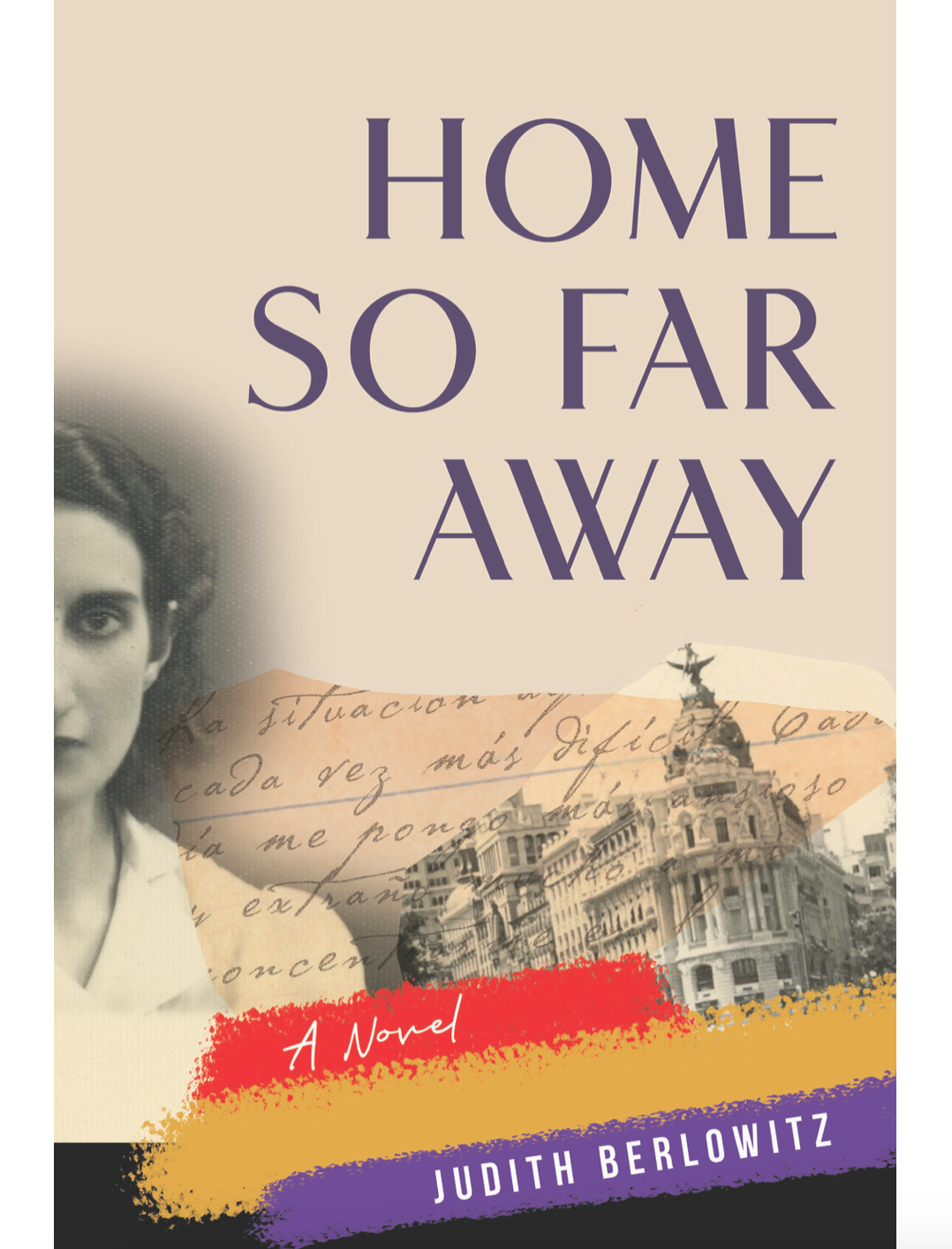

As a nurse and translator, Klara’s life and work fascinated Berlowitz, age 82, and led her to write her first novel, Home So Far Away (She Writes Press, June 2022 release), a deeply moving fictional account of the Spanish Civil War as imagined by an intrepid feminist activist.

Berlowitz’ years of research, coupled with Klara’s imagined daily life, make Home So Far Away an affecting work of historical fiction. She spoke to Lilith’s Eleanor J. Bader about the book in early March.

Eleanor J. Bader: How did you first learn about Klara Philipsborn?

Judith Berlowitz: Back in 2005, I was invited to the premier of an opera about Robert Oppenheimer called Dr. Atomic, and as I got dressed, I pulled a bracelet out of an old watch box that I’d inherited from an aunt. A note fell out of the box, saying that the bracelet had belonged to Klara Philipsborn, my aunt’s aunt.

An internet search led me to someone named Tom Philipsborn, who told me that I had found his grandmother! Shortly thereafter, he invited me to his home in Chicago and installed me in a guest room piled with information about the Philipsborn family. I spent days reading and later continued my search. The result was a book: From the Family Store to the House of Lords, which I self-published in 2015.

While working on that project, I read an article about the International Brigades, groups of fighters from all over the world who went to Spain in 1936 to fight the fascist coup. One cited Gestapo record mentioned “a persecuted Jew” named Klara Philipsborn. It gave her date of birth and her wartime location near Toledo, Spain. I continued to search for other documents that mentioned her. These were the sparks for Home So Far Away.

By the way, the images included in the book are all real; family photos and digitized newspapers and communiqués of the period.

EJB: How did you research the Spanish Civil War?

JB: Mostly sitting on my tuchis in my little office, although I did spend two days at the Tamiment Library in New York City where I found a photo of Klara with two other women which I included in the book.

The newspapers digitized by the Spanish National Library helped me understand the events and the ideological positions of the newspapers and the factions that existed. RGASPI, the State Archive of Russian Socio-Political History, was another major source of information. Lastly, there were Facebook groups created by history buffs with whom I made contact; Philipsborn family members provided added insights. For example, Klara’s nephew described her as a “firebrand.”

All told, I discovered about 20 documents with Klara’s name, many of them contradictory.

EJB: Did Klara really know Albert Einstein?

JB: Gerda, her younger sister, was friends with scientist Leo Szilard, who rented a room in the Philipsborn home in 1927. He and Einstein were real-life colleagues but the details about Einstein and Klara are fiction.

EJB: Klara also had a sex life as an unmarried woman. Was that invented?

JB: Pretty much, yes. But Comandante Carlos was a real man and I did find an account that discussed her obsession with Carlos. This was the catalyst for that part of the book. I also found references to a man named Ernst, another love interest, an ambulance and tank driver.

EJB: Why did you write the book as a diary?

JB: I wanted to hear the story in Klara’s voice and this was the best way for me to do this. I also wanted the novel to have an inconclusive ending since we really don’t know what happened to Klara after she was forced to leave Spain.

In 1938, all international participants in the war were expelled from Spain; by then, Klara felt thoroughly Spanish. As a Jew, her German citizenship had been revoked. She was legally stateless.

EJB: What was the biggest challenge in writing Home So Far Away?

JB: I’m a recovering academic, so writing historical fiction in an easily digestible and interesting way was difficult. How to engage the reader with facts and figures as well as human emotions and expressions? My editor at She Writes was really helpful. She would ask me, ‘What do you think Klara would feel here?’

EJB: Have you met any of Klara’s descendants?

JB: Klara has no known descendants. Her brother moved to the US and died in Berkeley, California, in 1973, but we never met. He and his wife, a psychologist, had three daughters, and I’m in regular touch with them. Klara’s younger sister, Gerda, ended up teaching at an Islamic University in India. She was also a professional singer. Klara’s elder sister, Liese, escaped Germany with her husband and two sons and ended up Australia. I’m in touch with the sons’ descendants.

EJB: Did you find anything surprising in your research?

JB: The degree of antagonism between communists, socialists, and anarchists was surprising to me. They actually considered each other enemies.

EJB: Klara lived as a feminist and witnessed feminism in Spain. Was this an accurate representation?

JB: Yes, and that was another surprise. Women were eager to introduce gender rights into their lives, and pushed for the right to divorce, the right to access abortion and contraception, the right to vote, and demanded that they be treated with respect. They were also very willing to put on overalls and pick up guns to fight for democracy.

In the book, Klara facilitates a group for the few female students at the medical school where she worked as a lab assistant before the civil war broke out. Women received the right to vote during this time.

EJB: Have you, like Klara, been personally involved in activism?

JB: I’ve been anti-war practically since infancy, and I’ve been part of Women in Black, an international feminist anti-war group, since 1988.

EJB: Klara hides her Jewishness when she arrives in Spain. She knows that her mother’s brother, her beloved uncle, lives as a Catholic in Seville. Was she simply following his example?

JB: When Klara first visits Seville in 1925, she sees people’s antisemitism first-hand and she may have unconsciously absorbed that being Jewish could cause problems for her. By the time she moves to Spain in 1930, she decides to pass, though never converting. Although she had never been super-religious, she was still a cultural Jew. Having access to Jewish food is important to her and she gravitates to other Jews she meets in Spain.

Klara’s uncle was a real man and I’ve reached out to a few of his descendants. None of them had any idea that he was Jewish.

EJB: The novel has already received a lot of praise. That must be really heartening.

JB: Yes! I’m 82 years old and am thrilled that I took to writing historical fiction. I’m proud that the book is getting out in the world and look forward to in-person and virtual events to celebrate its release. I feel like, after a lifetime of working in isolation as an academic, I’m finally busting out!