Arlene Rush Pushes Artistic Boundaries

Whether her medium is sculpture, installation, collage, or mixed-media, artist Arlene Rush challenges artistic boundaries. Her work is often provocative, mining contemporary politics and culture to address racial and gender disparities, capitalist excess, threats to democracy, and progressive resistance.

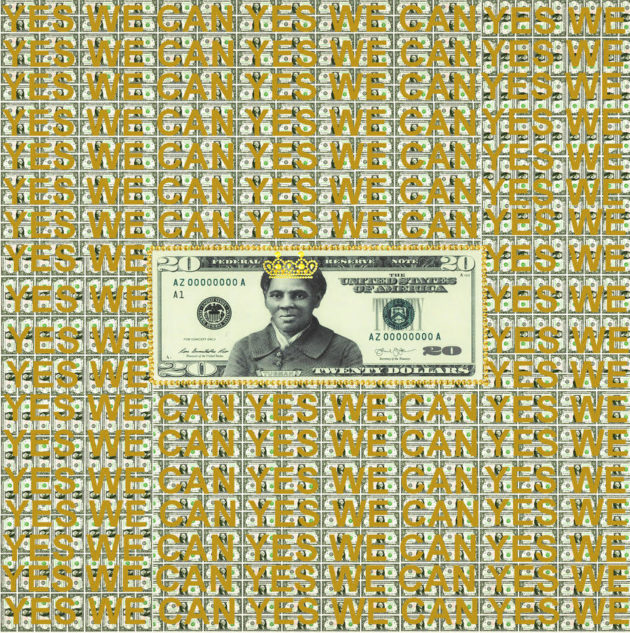

Her series titles telegraph her focus: My Body as a Battleground; Current Affairs; and Turning Lemons into Lemonade, among them. There’s also homage to people Rush admires, with Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Harriet Tubman frequently evoked.

Not surprisingly, Rush’s current projects have been kickstarted by the COVID-19 pandemic; new work interrogates loss, decay, and the reclamation of humanity as the virus recedes.

Widely shown throughout the US and in France, Germany, and Wales, Rush’s work is in numerous private collections as well as in the permanent holdings of the Center for Emerging Visual Artists; The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; and the Mount Sinai Cancer Center.

Rush spoke to Eleanor J. Bader about art-making and political messaging from her light-filled studio in Manhattan.

Eleanor J. Bader: Have you always made art?

Arlene Rush: I grew up in the Parkchester section of the Bronx and in my earliest years I was encouraged to do what I loved, which was art, but as I got older I was discouraged from making this my profession. My parents grew up during the Depression, so having enough money to be financially secure was emphasized. In fact, I grew up not knowing that you could make a living through art. That realization came much later.

But I may have been drawn to art for another reason as well. I had, and still have, severe learning issues, which I now understand as dyslexia. I also have trouble processing information. As a child, art was my way of going to a world where I felt comfortable and a means to communicate.

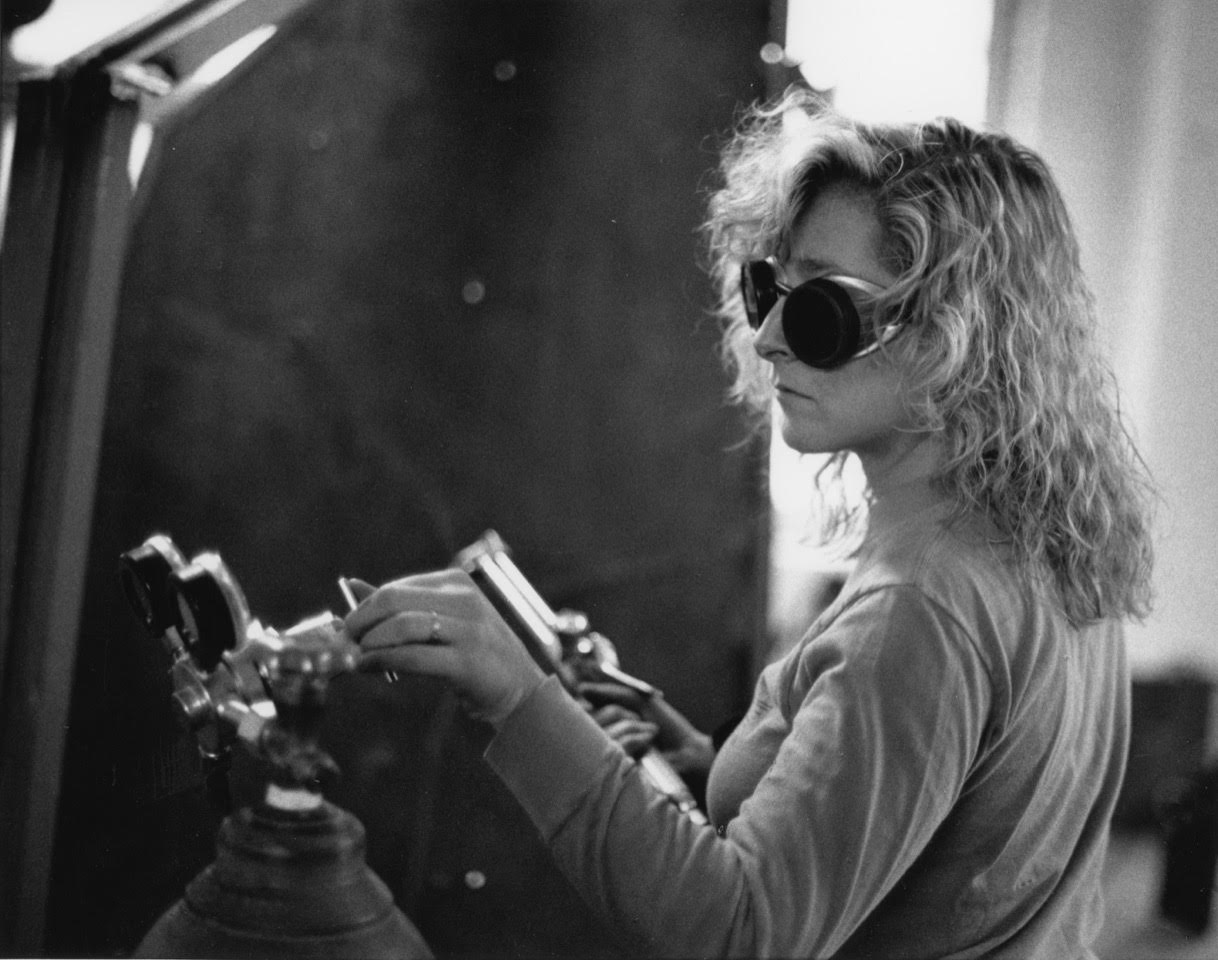

EJB: How did you learn sculpture? You’ve worked with steel so had to learn welding and construction skills, right?

AR: I started learning sculpture in high school. I had a teacher who encouraged me and taught me to use various materials and tools. He was critical, but supportive. But when I got to Queens College, there was not a single female sculpture teacher so I really did not have a mentor. There were male teachers, of course, who were womanizer types. They saw that I was really serious, and one teacher was extremely helpful in terms of instruction albeit not in helping me launch my career.

EJB: Does this mean you’ve had to work day jobs to support your art habit?

AR: Yes. For a short period I worked in interior design and did project management, design and sales. I’ve also done architectural restoration, worked in catering and been a staff recruiter in the furnishing industry. One of my favorite jobs was teaching art to women with cancer through what was then called The Creative Center for Women With Cancer. It’s now called The Creative Center and has programs for people of all genders.

Thankfully, I’ve had some great opportunities and have had periods when I’ve made art full-time, without an outside job. For example, when I was working in interior design, one of my clients knew that I was an artist. She invited me to meet, and paint with, artist Joseph Wolins (1915-1999). Wolins lived and worked in Westbeth Artist Housing, a huge West Village development that opened in 1970. Wolins was very jaded about the art world but it was a gift to paint with him and he let me use his studio to paint on other evenings and weekends when he was not there.

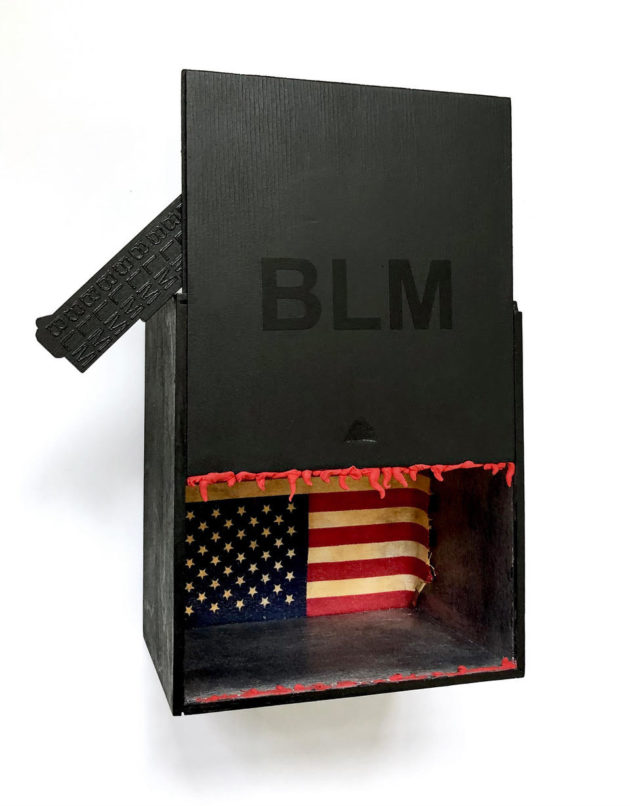

BLM 2020 Wood, silver leaf, vinyl lettering, fabric, glue and acrylic 8 ¾” h x 7” w x 4” d

Days After I 2011-2012 Digital print 30″ h x 22 ½” w

ejection, Reject, Re… Installation at Pen and Brush 2019 30 of the 38 envelopes, archival paper, museum board, resin, acrylic, metal leaf, polyurethane, and colored wax Overall installation 119″ h x 179″ w x 9″ d (approx.) Dimensions Variable

Notorious RGB 2020 Surgical mask, pearls, crystals, and ink 3 ¾” h x 10 ½” w

EJB: How did you begin making huge steel sculptures?

RA: I finished college in 1978 and by the end of 1985, I left interior design. By 1986, I was making art full-time. One of my former clients commissioned me to do some pieces and I was soon making huge welded steel sculptures at the Sculpture Center, then in Manhattan. I later found an 800 square foot studio on West 26th Street, right across from my current studio, and was in heaven.

Unfortunately, it took me 10 years to sell my first steel sculpture but I kept making art. I always had an assistant, someone to help me move the sculptures and hold the torch while I forged the steel. These people worked for free; in exchange, I taught them to weld.

Early on, people thought it was really cool that a woman was doing these massive works. At the same time, there was so much sexism. People would come to my exhibitions and ask me to tell them the name of the man who’d made each towering piece. They’d ask me about my husband. After a while, I started to use my first initial, so I signed my work “A. Rush” to try and evade this response.

EJB: Did this make you a feminist, or more of a feminist?

RA: I grew up with a strong mother and a dad who taught me to throw a football. My father actually boxed with me. I played with dolls, too, but my upbringing helped create my ideology. As a young woman, I was intuitively against discrimination, whether it was gender, race, age, sexual orientation, or identity. I’ve always stood up for myself and others, and was even a bit righteous. But somehow I didn’t learn about the feminist art groups that began forming in the 1970s and 80s. Later on, I met women who were activists and have a number of feminist writer and artist friends.

EJB: Why did you stop working in steel?

RA:In 1998 or 1999 I transferred to a more conceptual model of art-making. I stopped working in steel since I wanted to express more conceptual ideas and I began to overtly address issues of gender, identity and inequality.

I started creating androgynous heads and looking at what gender represented. Some of my other work incorporated bras, glistening faux diamonds, and faux fur, but the heads were and are in neutral colors: Gold, orange, terra cotta, white, and black. They were meant to strip away gender identity and just be “human”.

EJB: Does your art always convey a message?

RA: Yes. During the Trump administration, the threats to democracy he represented, and the COVID-19 pandemic, how could I not? I think it’s important for me to speak out, to bring to light controversy and to make a difference. I hope my work will survive for generations so that in the future people will understand that there was resistance. I also want them to know that there was wide-scale support for Black Lives Matter.

Overall, my favorite themes are those that unite us, but my work is not and never will be mainstream. I don’t make pretty or quiet art although I care about aesthetics. My work talks; it communicates.

EJB: Tell me about some of your favorite projects.

RA: A few years ago, I found a stack of rejection letters I’d received over the years: ‘We don’t show women artists;’ ‘We regret that we can’t fund your work.’ I made 38 oversized paper and resin envelopes with paint and gold metal leaf for an installation called Rejection, Reject, Re…

Then, in October 2019, I did an installation in a telephone booth on West 14th Street in Manhattan. I installed the plastic-coated letters inside the booth; over three days, people came by, read them and left uplifting messages. Some left rejection letters of their own. It was great fun.

Another favorite was done a few years earlier, when I created My Body As a Battleground, an 4-piece series which documented my experience with breast cancer in 2011.

And then there was the commission I did in 2016 to pay tribute to, and commemorate, the 40th anniversary of Ntozake Shange’s “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf.”

EJB: How did COVID impact your creativity?

Believe it or not, I was in 18 group shows in 2020, some of them virtual and some of them in person. I even sold some art.

I’ve used the pandemic to learn and create create NFT’S, Non-Fungible Tokens, a unit of data that is stored on a digital blockchain that certifies that all of my digital assets are unique.

I’ve also made numerous masks with images of my heroes, including Harriet Tubman, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Black Lives Matter activists. I did a tribute piece to Justice Ginsburg after she died [see above] and took part in the US Postal Service Project. That project means a lot to me because my father worked for the Post Office. It was what he considered a good job, with benefits and a union. During the worst of COVID, the Postal Service was under constant attack and a project was developed to help bolster it. Artists were encouraged to mail art to other artists through the USPS to help boost revenue. Hundreds of artists took part and are still participating. Christina J. Massey has done an amazing job launching this effort.

I recently finished a work called I’m Still Here, which will be my first minted NFT. It will be shown at Every Woman Biennale opening on June 24th. As you can probably guess, it addresses the struggles caused by the virus. But throughout, and perhaps most importantly, the pandemic pushed me to take better care of myself, my friends, and my community.

Perils

2002-2020

Resin, fiberglass, acrylic, metal leaf, glass, N95 mask, and wood

12″ h x 9″ w x 13 ½” d

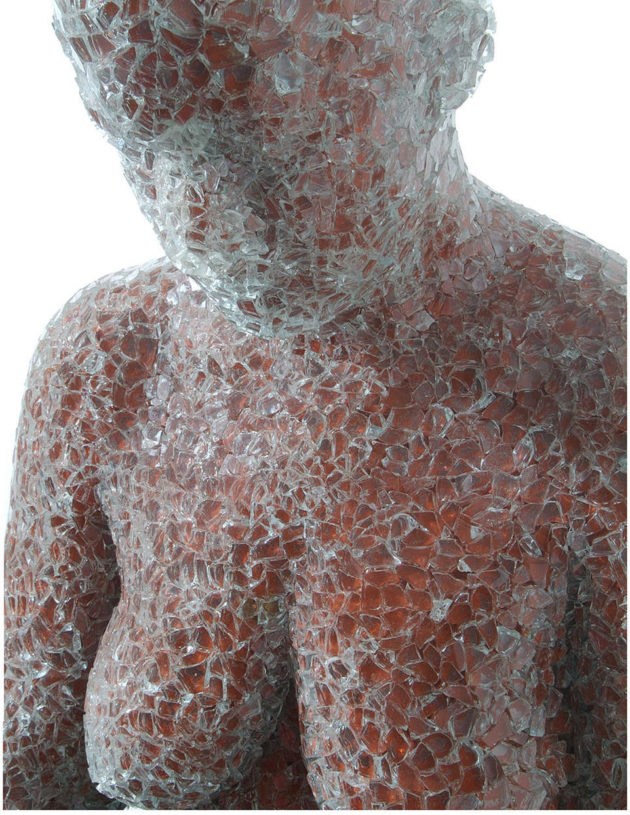

In Waiting

1999-2004

Resin, fiberglass, glass, foam, metal, wood, steel, and acrylic

Yes We Can

2020

Digital archival print

48″ h x 48” w