A Twelve-Year Old Fleeing the Pograms

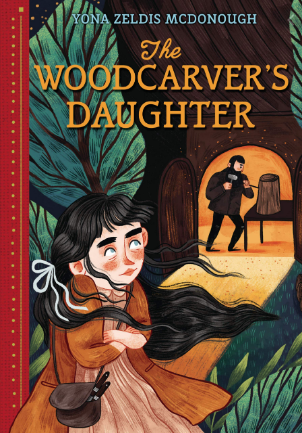

Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough, is the prolific award-winning author of eight novels and 30 children’s books. She talks to Lilith editorial assistant Arielle Silver-Willner about her new middle-grade novel, The Woodcarver’s Daughter, which explores the Jewish immigrant experience and the confines of traditional gender roles, from the perspective of twelve-year-old Batya, as her family flees Russia during the Pogroms of the early 19th century. The Woodcarver’s Daughter hits shelves on April 1st, 2021.

ASW: It’s great to have this chance to speak with you about your newest book—I have a very clear memory of you coming into my elementary school and reading one of your earlier children’s books to my first grade class (almost 20 years ago!) so this feels very special.

YZM: That is so sweet! And I remember you too. You were a very engaged, serious girl. And enchanting. Like a little dewdrop.

On that note, I’d love to begin by asking you: Why this story? Why now?

This story was sparked by a visit to the Museum of American Folk Art (an institution very supportive of women’s art in general) to see a show of carved carousel animals. A parenthetical wall note mentioned that no women were represented because girls could not join the guild, and so had no access to the kind of training, tools and material they would have needed to do this kind of work. Well! Although this didn’t surprise me, I didn’t much like it. And immediately a character popped into my head—a girl who wanted to be a woodcarver, like her father. I was intent on writing her story.

You have such a keen sense of what it’s like to be a twelve-year-old girl—the balance of emotional maturity and childhood anxieties. What informed your understanding of these characteristics?

I’ve never quite left that part of me behind. That twelve-year-old girl is still alive and present in me. I never feel I have to reach very far. Flannery O’Connor said that anyone who survived childhood had all the material she ever needed to become a writer. I know what she meant.

Details of Jewish life are central to your story, but you make them accessible to all readers by offering context clues and definitions of yiddish words. Who do you imagine your audience to be? What do you feel is the significance of having non-Jewish children read Jewish stories, versus Jewish children?

I do think this story will have an immediate appeal for Jewish children. Our collective experience as immigrants very much shapes and forms our identity so I think the events described will resonate with them. But I also hope the story will provide a window into an aspect of our history that non-Jews will find interesting as well.

You don’t define “pogrom,” like you do other words, but rather slowly show what it means by taking us through one—is there a reason for this, considering that many young readers may not know this word?

That was not an intentional choice, but you are right, that’s how the story unfolds. I knew I wanted to portray the pogrom, not in too gruesome a fashion, but in a way that would suggest the horrible fear that Jews must have undergone, again and again, when these killing sprees took place. That was very important to me—it’s a piece of our history that is worth remembering and documenting.

There seem to be several parallels between the family’s experiences in Russia and in New York. Can you talk a bit about this?

You are a very astute reader; I had not actually thought about this consciously either. But it’s true that Batya and her family experience a sense of otherness in both countries. In Russia, their otherness comes from being Jewish. In America, it’s about being new and unfamiliar with the language, the culture, the protocols. In Russia, they are not able to overcome that sense of difference; the deeply ingrained prejudices won’t allow it. But in America, there are opportunities for them to adapt and eventually belong.

You make a clear point about breaking traditional gender roles in the story. How do you suggest that young readers today can incorporate this lesson into their 21st century lives?

I hope they do! Batya had much to overcome in terms of gender stereotypes; today’s girls, less so. But it’s good not to take that for granted because we’re not all that far away from a more restrictive time. Women have only had the vote in this country for about 100 years—kind of shocking when you think about it. We’re still paid less and experience a double standard in the workplace and are expected to both function in that world and assume a large share of the work at home. And when you look at what things are like for women around the world—honor killings, genital mutilation and more, you realize there is still plenty of work to be done.

The young Jewish girl immigrant story is popular in the middle grade historical fiction canon—what sets your story apart?

I don’t know of any other story that deals with a girl who wants to be a woodcarver. And the way that the woodcarvers of Eastern Europe, hounded out of their homes, were able to reinvent themselves here, well, that’s very inspiring. Back in their home countries, they carved synagogues, bimas, Torah scrolls. In America, they used their talents for secular purposes, and became part of the Golden Age of the Carousel, carving animals with beauty, grace and mastery. There wasn’t a single template; these craftsmen developed distinct individual styles and became known for them. It’s a good example of our ingenuity, our ability to adapt, which is in part responsible for our continued survival. I wanted to shine a light on that story, and then to give a feminist twist. Because that’s one of the joys of writing fiction—you can create not just the world around you, but the one you’d like to live in, as well.