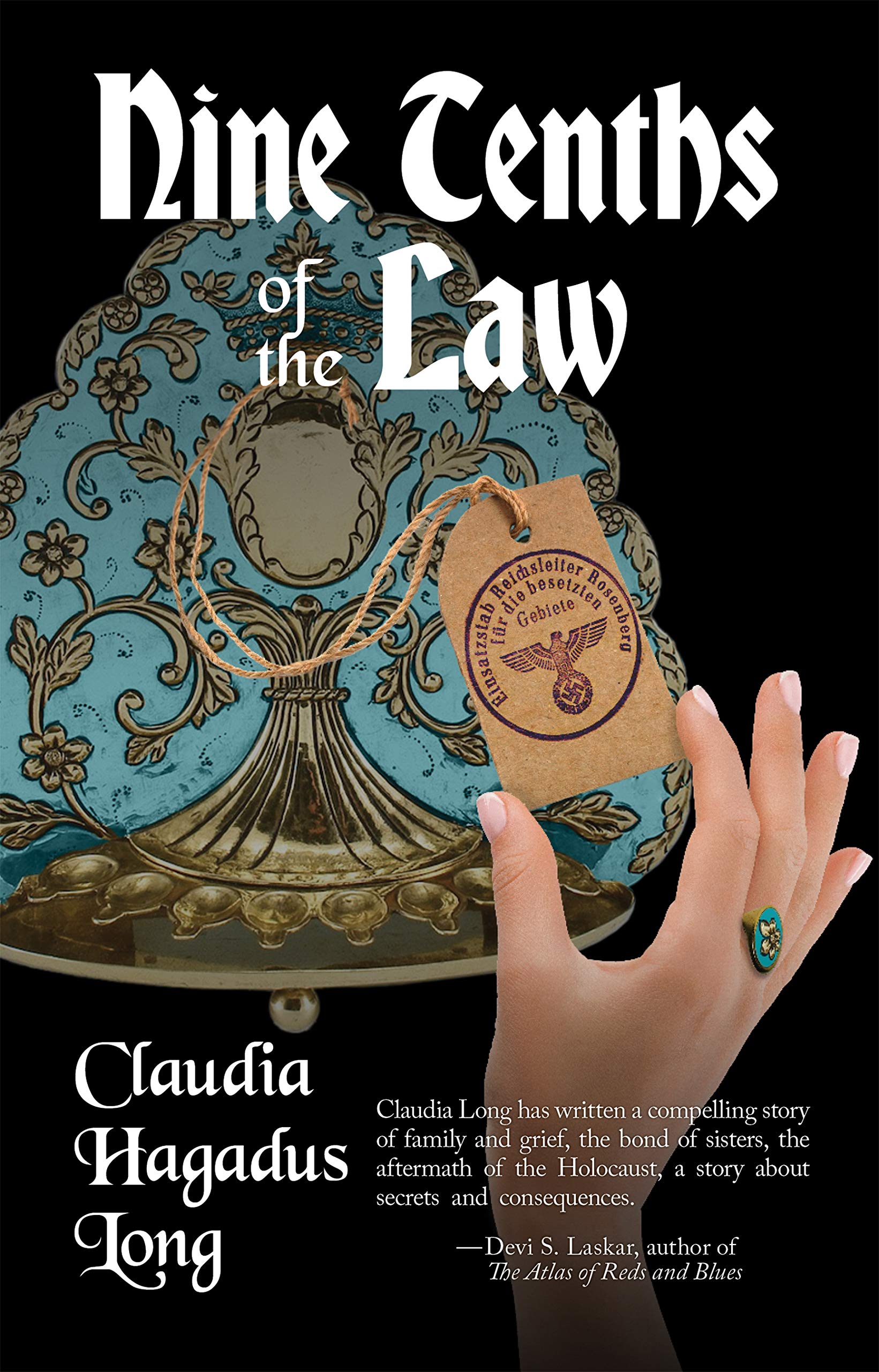

Two Generations of Women …and a Stolen Menorah That Haunts Them

YZM: Is the menorah that Zara and Lilly are trying to find based on an actual menorah that you’ve seen or that your family owns?

CHL: One day, over forty years ago, my mother and I went to the Jewish Museum in New York City, and she showed me a menorah in their collection. “We had one just like that,” she said to me. I was young enough not to pursue it, but old enough that I should have. She touched the glass case and said it again. She was telling me, That was mine. Times were different then, in 1977, and neither of us was able or willing to say or do anything about it. As to what it looked like, though, no. The ring in the book is real, I wear it every day, and I made the menorah look like the ring for both plot and intrigue.

YZM: Both sisters have a different response to the inherited trauma of their mother’s Holocaust experience. Care to comment?

CHL: The sisters are fundamentally feeling the same thing; they’re both traumatized. It shows up in different ways, though. Lilly is a little on the promiscuous side because she’s looking for the love that she couldn’t get at home. Aurora was forced into overtly expressing her sexuality at an early age to survive, and Lilly takes on that sexuality. Zara shuts down, is sarcastic and ignores the family stories, the way Aurora sealed off her past and her own emotions. But both are exhibiting parts of the pain their mother felt.

YZM: Zara is at times inhabited by her mother’s memories and voice—what was your intention in doing that?

CHL: Aurora needed a voice in the story. Zara’s pain needed an outlet. So it seemed natural that Aurora would speak through Zara, especially when Zara wasn’t willing to speak her truth directly. It was interesting that Lilly was willing to shade the truth when it suited her personal needs, but was still more willing to face the family’s secrets directly. Zara, who prided herself on her honesty and fact-based reactions, couldn’t look the trauma in the eye, but had to have it “seep out,” in Zara’s case, through Aurora herself.

YZM: You’re currently a lawyer and currently mediate employment and business disputes. How does that background and training come into your work as a novelist?

CHL: Although my books have –with one exception– very little actual law in them, I think that my legal training insists that there be no plot holes, that the point of view remain consistent, that only things the narrator can see or feel can be described. No head-hopping for me! No hearsay!

I also work daily with people who are traumatized by mistreatment, who are accused of behaviors they find reprehensible; all of these people are faced with difficult choices. I see many different slices of life, and I knew professionally that listening to everyone, with a radically open mind, is paramount. Rarely do folks set out to do wrong. Rarely are people single-minded in purpose or one-dimensional in reaction. To achieve a settlement that both sides can buy into requires that I understand the real driving forces behind actions as well as the layers of reactions to the events. I think that this understanding helps me write characters that are multi-faceted, with varied motivations, strengths and weaknesses. At least I hope so!

YZM: ”…I will expiate the guilt of not having suffered,” and “…if you don’t acknowledge the pain, it manifests in your life and lives of generations to come.” These two sentences seem to sum up the novel’s themes; would you agree?

CHL: Much is written now, as we, the generation that comes “after”, write our own stories. Until ten years ago or so, inherited trauma was not a topic, but our generation has made our parents’ trauma, in part, about us. I know that personally I always felt the guilt of not having suffered. And Aurora’s voice, her terrible memories, are made from my own mother’s memories. In a sense, Nine Tenths of the Law is an acknowledgment of the pain manifesting in my life, and my hope that it will not manifest in the generations to come.