When Women Make Holocaust Movies—And Take On God, Moses & Exodus

In our own time of political evil, we hunger for tales of Jews, Muslims, Christians standing up to fascism. All the better if these stories are true. Fortunately, all four films take us there.

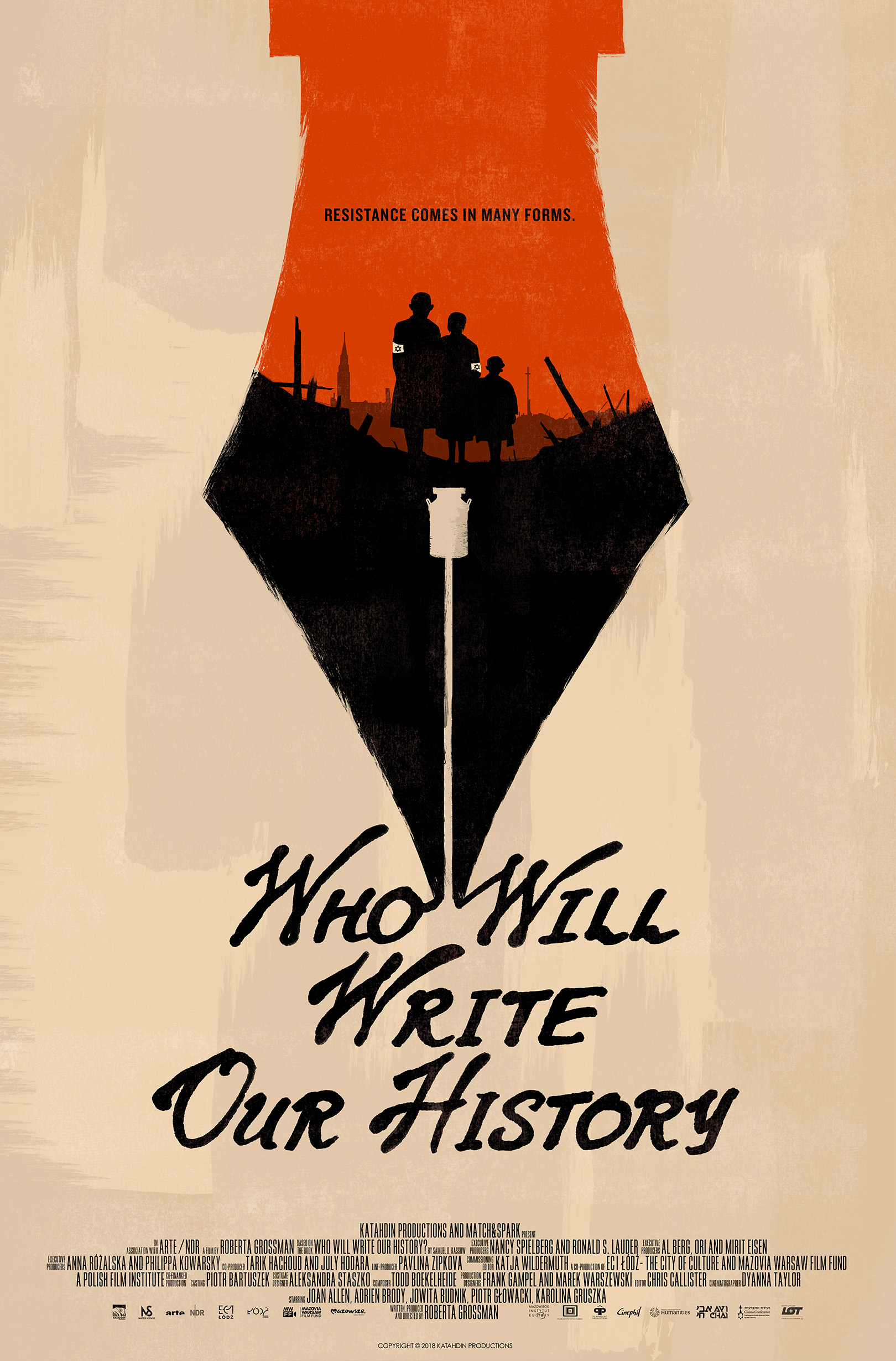

What’s amazing about writer-director-producer Roberta Grossman’s “Who Will Write Our History” —the story of the secret archives of the Warsaw Ghetto – is the way it continues to challenge our beliefs. Because even though 60,000 pages of material detailing the strength, resistance and grit of survivors have been meticulously curated in the Jewish Historical Institute in one of the few buildings left standing in the Warsaw Ghetto, the image of Jews as weak, based on Hitler’s propaganda films, continues to hold a place in our imagination. This new film, based on historian Samuel Kassow’s book of the same name, lets the Warsaw Ghetto Jews tell their history.

The narratives of the hidden documentation and its recovery make two of our history’s great adventure stories, and this film gives them their due. Under the Yiddish code name Oyneg Shabes (the joy of Sabbath), historian Emanuel Ringelblum and his secret team risked their lives collecting records of the Warsaw Ghetto as it was happening. They hid diaries, poetry, jokes, beggars’ songs, posters, drawings, reports of smuggling, reports on the roles of women and children and underground schools, cabaret music for starving audiences. They archived questions: What does it mean to walk by dying people in the street—does it show callousness or strength? They started documenting the concentration camps’ mass murder for the future prosecution of the killers. And they smuggled out details to the BBC, hoping to be saved.

The Ringelblum archives were based on the model of the YIVO collection, started in Vilna in the 1920s, a Jewish history not of rabbis and philosophers but of ordinary people. Grossman’s previous credits include “500 Nations,” an eight-hour Native American history; “Blessed Is the Match: The Life and Death of Hannah Senesh”; “Hava Nagila (The Movie)” all with filmmaking and life partner Sophie Sartain.

For “Who Will Write Our History” (in English, Polish and Yiddish, with English subtitles) Grossman focused on Rachel Auerbach from Oyneg Shabes, which includedsome 60 Jews of diverse backgrounds and politics.

Auerbach was an experienced journalist, a member of the Polish-Jewish intelligentsia. Although the film makes the point she was doubly excluded as a woman and a Jew, her pre-war achievements would seem to prove otherwise. Ringelblum convinced Auerbach to remain in the Warsaw Ghetto, doing the women’s work of running one of the 100 ghetto soup kitchens. Feeding starving Warsaw Jews and a flood of refugees gave Auerbach a unique vantage point. She stayed, kept a diary, and was one of only three Oyneg Shabes members to survive. After the war, as an Israeli citizen, Auberbach created the Survivors Testimony Department at Yad Vashem, and convinced the state prosecutor to base the Eichmann trial primarily on survivor testimony.

Would a male filmmaker have focused on Rachel Auerbach rather than on Ringelblum or one of the other prominent Oyneg Shabes men? No way to know. But with Auerbach as a focal point, “Who Will Write Our History” takes on the power to do what film does best: bring emotion to facts.

In muted tones, the film recreates Auerbach’s picking her way through the ruins of the ghetto. She says that what looks like an unseasonable snowfall is feathers from abandoned bedding. Her words come straight from her archived diary: “Oh, the crying of things abandoned forever by their owners, becoming degraded in strange hands like corpses not buried who have no one to do right by them. He who has not seen the weeping of dead things, he has not seen or heard in his life any sad things.”

With “Who Will Write Our History” now in theatrical release, hopefully the Oyneg Shabes archives will finally become popular knowledge, telling the Warsaw Ghetto story by the Jews who lived it.

For those of us seeking Muslim-Jewish understanding, “Mohamed and Anna: In Plain Sight” might just be the unicorn that gives us hope. It’s the story of an Egyptian doctor in Berlin who risked his life to save a Jewish teenager from the Nazis by disguising her as a Muslim. Most extraordinary, Mohamed Helmy kept standing up to the Nazis even while flattering them to accept a brown-skinned Muslim as one of their own. And they did.

The documentary in English by Israeli director-producer Taliya Finkel premiered at the NY Jewish Film Festival and, hopefully, will make the festival rounds and go onto commercial distribution.

The film is a bit of a companion piece to “The Invisibles,” the stories of four Berlin Jews hiding in plain sight after the city was declared judenfrei” (free of Jews). The film, combining re-enactments with interviews of the actual “Invisibles,” premiered at the 2018 NY Jewish Film Festival and is now in commercial distribution.

Near the end of “Mohamed and Anna,” surrounded by endless Kafka-esque filing cabinets, we meet the director of Yad Vashem’s Righteous Among the Nations Department. The one thing all the righteous have in common: “At a certain point, they decided they were willing to act against what society was doing.” Why is this so hard for us humans?

Two other festival films worth noting:

“Chasing Portraits” is one American woman’s unstoppable quest to locate the paintings of her great-grandfather, artist Moshe Rynecki. This is not a restitution story. In English and Polish with English subtitles, it’s the search just to see the missing works of a talented Warsaw artist. His art was rooted in a vanishing Jewish life, and he wanted to stay in that life to the end in the Warsaw Ghetto. Like a smaller version of the Oyneg Shabes buried treasure, one bundle of the collection of 800 paintings survived. But great-granddaughter and first-time filmmaker Elizabeth Rynecki travels from North America to Poland to Israel in search of more Rynecki paintings. In the age of social media, her blog and film website keep reaching out for new connections. And since she’s more daughter than filmmaker, she’s also trying to get her father, a survivor, to open up. Above all, the film’s takeaway for me is: If you are truly determined to do something, do it.

“The Light of Hope,” (in Spanish, Catalan and French, with English subtitles) by Spanish director Silvia Quer, brings us into a women’s world of very pregnant Jews, Spaniards and gypsies fleeing the deadly Vichy refugee camps. “The Light of Hope” is Elisabeth Eidenbenz, a young Swiss primary school teacher. Her maternity hospital in an abandoned mansion in the Pyrenees delivered 600 babies to an uncertain fate. In this docudrama, with its U.S. premiere at the NY Jewish film festival, the gutsy Eidenbenz takes on the Vichy powers. Much like Rachel Auerbach with her Warsaw Ghetto soup kitchen, she does so despite doubts over what awaits anyone who survives.

****

And now for something totally different, “Seder Masochism,” the feature length animation by Nina Paley, made its New York debut at the NYJFF. It’s the perfect Jewish feminist tour-de-force for Passover.

Paley’s all-star dancing cast includes the great goddesses and fertility figures. Watch an entire chorus line of pudgy, pendulous, undulating Venus of Willendorf figurines, 3,200-years young. Watch Moses, his head shaped like the two tablets of the Ten Commandments, smash the goddesses to the refrain of “The Things We Do for Love.” See the Haggadah’s four cups of wine explained by an animated and toothy Jesus at the Last Supper. See the Angel of Death at work in Egypt and watch centuries of men slaughtering other men to the “Exodus” theme song “This Land Is Mine.” Wack.

And watch the Homer Simpson-like God, crown atop non-stop flowing hair, with non-stop flowing moustache and beard, dollar bill eye of the pyramid incorporated into his very being. He is God the Father as in Nina Paley’s father, expressing his doubts in Judaism but believing in the seder to communicate his Jewish heritage to his kids. Paley takes on God the Father in the figure of a little black scapegoat.

If this seems like a lot for 78 minutes, with English, French, Bulgarian, Hebrew and Aramaic with English subtitles, just know there’s more, maybe too much more, including the bombing of the World Trade Center.

But there’s cause for hope. The fertility figures and goddesses are not so easy to vanquish. And Paley, ignoring her father’s concerns for her economic security, has made “Seder Masochism” available for free.