Forty Years from Now: Perspectives of Women in the Rabbinate

Despite her deep conviction and self-confidence, Priesand confronted discrimination and sexism throughout her training and career. Classmates, and even professors, assumed she was enrolled in rabbinical school simply to marry a rabbi. There was no on-campus housing for her, few women’s bathrooms were available on campus, and male faculty (at that point the rabbinical school faculty was exclusively male) would begin class by addressing students as “Gentlemen.” After ordination, many people referred to her as “Rabbi Sally” rather than “Rabbi Priesand,” though her male colleagues were addressed by their surnames. As Rabbi Priesand explained to the audience, she has moved through her career always conscious of the fact that she is the first woman rabbi, at least the first formally ordained, and has made her life choices—focusing on her career, not having a family—knowing that many people have judged the entire concept of women in the rabbinate using her as their measuring stick.

She helped set the stage for other women, including the other panelists. Rabbi Schorr was ordained in 1999, and Rabbi Berkowitz in 2008. Rabbi Schorr has never served in any pulpit where there has not already been a woman, while Rabbi Berkowitz is the first woman to serve her congregation, and worked to counter the congregants’ perceived need for a “father figure.”

Being a woman and a rabbi simultaneously has not been easy, judging from the experiences presented by the panelists, who have had to make difficult choices to balance serving God with having a family. Rabbi Priesand made the conscious choice not to have a family. Others, like Rabbi Schorr, have stepped away from the pulpit to focus on their children. And many other women rabbis have worked, contributed to the community and raised children, all at once. There’s a whole generation of women, those who came immediately after Rabbi Priesand, whose experiences are crucial to our understanding the particular challenges for women in the rabbinate. Even if the stained-glass ceiling has been retracted (though not entirely broken), these women have had to push the boundaries further. They created new models of rabbinic leadership, like job-sharing, or simply being rabbis who go home for dinner with their family before a committee meeting. They have advocated for equal pay with their male peers, became the first women to serve as senior rabbis, and normalized the idea of rabbis being pregnant, taking family leave, and raising children.

So what comes next for the Jewish community? We have made great strides, but this cannot be where the journey ends. Even our language gives away the biases that still exist. After all, while we have used the phrase “woman rabbi” here, it would feel odd to specify “man rabbi.” Women at the pulpit should not be the “other.” And neither should rabbis who present in other “nontraditional” ways, such as LGBT rabbis, or rabbis who have disabilities, for instance. This liberal movement’s ability to confront new challenges will be determined by our ability to learn from the past and look honestly at our present, as evidenced by the public conversation among these women, all three illuminated rather than held back by stained glass panels and ceilings.

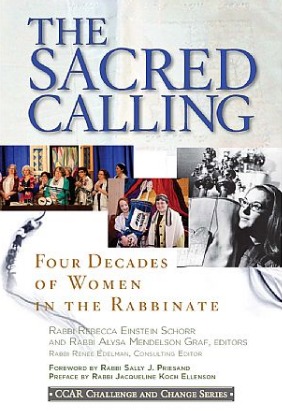

Rabbi Hara Person is publisher of the CCAR Press, which recently released The Sacred Calling: 40 Decades of Women in the Rabbinate, a retrospective anthology.