The Torah of Johnny Cash

Several years ago while preparing food for Rosh Hashanah, I came across a Spotify recommendation for Johnny Cash’s album My Mother’s Hymn Book.

Growing up Jewish, I had never previously opened a hymn book or heard these songs sung in person. As I listened, I was struck by a familiar voice I had come to know and love, a clear and raw voice juxtaposed with a complicated longing for God that I also recognized in myself. In My Mother’s Hymn Book, Cash articulated my own spiritual desires for eternal life and the promise of reuniting with departed loved ones.

The strength of his voice grabbed me during those final hours of the Jewish year. There was one track in particular I listened to on repeat, the first track titled Never Grow Old:

When our work here is done

And our life’s crown is won

And our troubles and trials are over

All our sorrow will end

And our voices will blend

With the loved ones who’ve gone on before

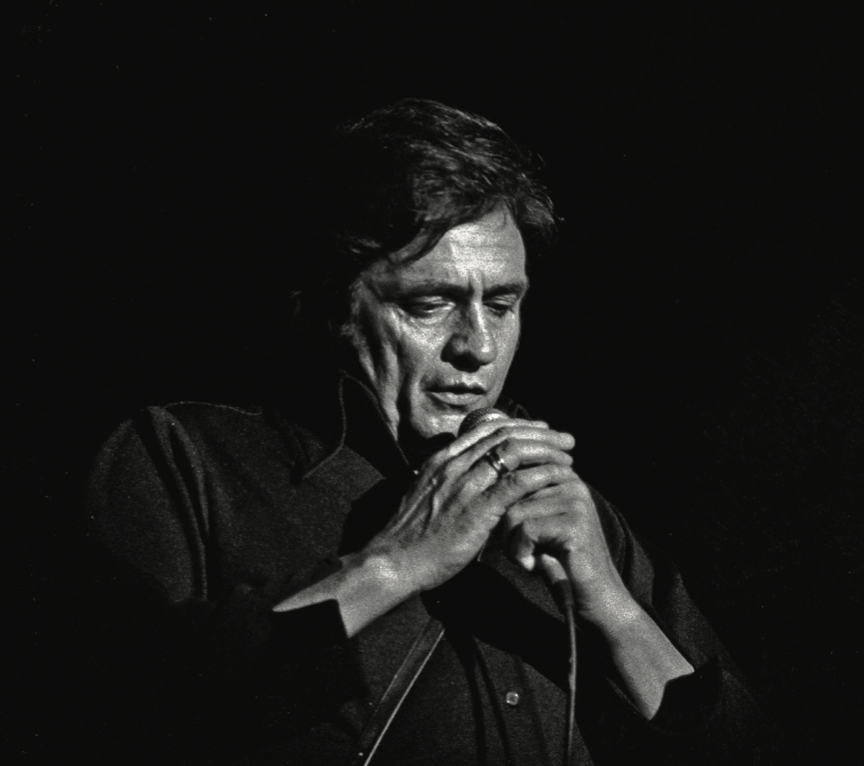

People are mystified by my connection with Johnny Cash. Cash was a Southern Bap- tist and there are some pretty big theological differences between Southern Baptists and Jews. And yet, when Cash sings, I hear our similarities over the differences. Music is greater than ideology. Music has always been able to produce feelings in a way written theology never could. As a rabbi immersed in theology, I know this first hand. When Johnny Cash sings, I do not hear divi- sions between Jews and Christians. When Cash sings all I hear is a universal yearning for the Divine and I am at once connected to him, to all seekers, and to God.

Cash’s book of poems, Forever Words, was put to music by various artists in 2018. The first track, “Forever/I Still Miss Some- one,” features a poem of Cash’s spoken by Kris Kristofferson over Willie Nelson’s guitar. Only forty-seven seconds long, the track ends as soon as these words have been spoken:

You tell me that I must perish

like the flowers that I cherish

Nothing remaining of my name

Nothing remembered of my fame

But the trees that I planted still are young

And the songs that I sang will still be sung.

According to John Carter Cash, these words were written by his father in the last weeks of his life. On face value Cash is speaking about his literal fame and mortality. Just as he predicted, his anthology of music outlived his mortal life; the songs that he sang continue to be sung. However, Cash offers a lesson more important than this: even the most famous can be erased from the future. And yet, he reminds us, there is a taste of something everlasting in our lives and we can have a part in creating it.

There’s another great figure who openly discusses his mortality and legacy: Moses. Towards the end of Deuteronomy, Moses knows he will die soon and he must prepare for his death. As a leader of the Israelites, he often expresses a concern that, without him present, the people will stray from God’s teachings. Perhaps to assuage Moses, God says to him, “Now therefore, write down this song for your- selves, and teach it to the children of Israel; put it in their mouths.” (Deut. 31:19)

The song God is referring to here is Torah. God commands Moses to write down and teach Torah to the children of Israel, that it should be in their mouths, on the tips of their tongue; an everlasting covenant that they should not forget.

The Alter Rebbe taught that there are gates to heaven that cannot be opened except by melody and song. Song has a way of breaking down our interior barriers to reach the parts of ourselves we’ve cloaked in fear and cynicism. Parts of ourselves that perhaps we’ve forgotten. Song reminds us that we all seek to be remembered.

Torah and Cash know that long after our bodies are gone from this world, the songs that we sing will live on.

Janine Jankovitz Pastor, “Johnny Cash Sings of Forever,” Lilith Online, September 2023.