Swimmers Against the Tide

Girl athletes who broke the boundaries, broke the records, and broke free.

This July, the European Maccabiah Games were held in Vienna, marking the first time that Jewish athletes from dozens of nations competed on a territory of former Nazi Germany. It’s a fitting moment to celebrate a group of exceptional Jewish girls who were exultant champions over 70 years ago as Hitler’s reign approached. They were the Hakoah Vienna women’s swim team, a group of athletes whose sports prowess was equaled by their political courage. My mother, too, was a girl in Vienna during these years, and my grandfather a Hakoah soccer player.

Inspired by the swimmers’ story, which I initially learned of from Yaron Zilberman’s 2004 film documentary, “Watermarks,” I interviewed some of the “Hakoah Girls” in Vienna, London and the United States. In their eighties and nineties, these remarkable women were still vital and energetic, sharing details from their iconic girlhoods as though little time had passed.

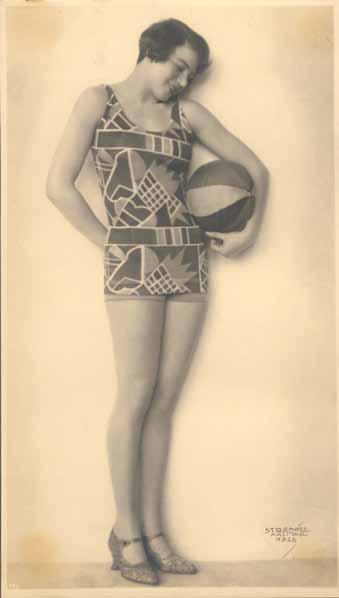

Their story begins in 1924, when 15-year-old Hedy Bienenfeld dove into the Danube canal and breast-stroked to first place in the annual, five-mile Quer durch Wien [“Across Vienna”] as half a million spectators watched from the river banks. Exercise — for amusement and for the sake of one’s health — had become very fashionable, and swimming was one of Austria’s favorite sports. Unlike other athletic events, the open-air race down the Danube had no entrance requirements; anyone, even Jews, could compete. When precocious Hedy secured second place the following year, and teammate Fritzi Loewy free-styled to first, the Hakoah swimmers became players in the close, competitive world of Viennese sports.

The Hakoah Vienna Sports Club was founded in 1909 in response to the “Aryan clause,” which restricted Jews from joining sports clubs. From the beginning, its mission was three-fold. First was to promote Zionism, particularly Max Nordau’s “muscular Judaism,” which aimed to subvert stereotypes of Jews as frail shopkeepers and pale scholars. Second was to strengthen community bonds and Jewish identity, particularly among largely assimilated Jewish youth. And third was to enter the then-burgeoning movement of competitive sports. The Hakoah soccer team, still legendary among soccer aficionados, was avant-garde in hiring professional coaches, and the swim team followed suit.

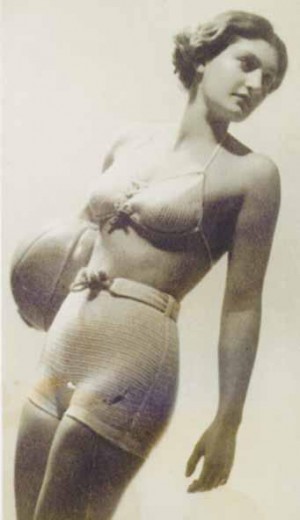

Hedy and Fritzi were blazingly modern girls. Gorgeous, gregarious Hedy became famous not only as a swim champion, but as a fashion model for Vienna’s leading magazines, supporting herself financially while still in her teens. After many lovers and beaus, she married the swim coach — Zsigo Wertheimer — a charismatic and gifted mentor 10 years her senior. Confident, bohemian Fritzi, reportedly bisexual, often sported a pet monkey on her shoulder. She carried on an affair with Dr. Valentin Rosenfeld, the director of the Hakoah swimming division, whose psychoanalyst wife, Eva Rosenfeld, was a member of Anna Freud’s inner circle. Because Dr. Rosenfeld, a lawyer, took on only penniless clients such as the Communist party, Eva supported the family by running a school in her garden, where the young Erik Erikson was a teacher.

By the early 1930s, Zsigo Wertheimer and Valentin Rosenfeld had become deeply and single-mindedly committed to building a star team from a second generation of swimmers. That a group of talented teenagers who loved the water could be trained by professionals in a systematized and rigorous way to excel was then a brand-new concept. The swimmers practiced several days a week after school and on weekends at the Dianabad, a pool housed in an elegant building bordering the Danube and the Jewish quarter. They were a close-knit group whose energetic lives included parties, galas and balls, as well as hikes in the countryside and lectures by cultural figures — including one enlightened physician who delivered the astonishing news that, contrary to popular belief, females did not have to take to their bed during menses. In the summer, girls and boys took up residence at Zsigo’s rigorous training camp at Lake Worthersee, a magical place where friend- ships deepened and romances blossomed, creating the lifelong memories universal to overnight summer camps.

Success, however, was always political. As the Jewish girls increasingly triumphed in the pool they engendered overt anti-Semitism. Hunky teenage boys from the Hakoah wrestling team accompanied the girls to away games, ready to step in should the tension erupt in raised fists. Coaches from rival, Nazi-sympathizing teams, disputing Hakoah’s win in a race, devised faux penalties and regulations that Hakoah coaches then worked to trump with elaborate arguments.

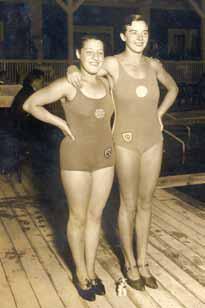

In 1935, the Hakoah swimmers competed in the second Maccabiah Games, held in Palestine, then a largely impoverished land of desert, and clearly an exotic adventure for the young cosmopolitans. The Hakoah girls led the opening parade through Tel Aviv while “pioneers” ecstatically cheered the arrival of 1350 Jewish athletes from 28 countries; soldiers from the British Mandate looked on. The swimmers triumphed in the newly built pool by the sea in Bat Galim, garnering the points that placed Austria first. Germany placed second. They toured the land on motorbike, waved to Bedouins on camels, boarded with chalutznik families, and returned to Vienna ardently Zionist.

In the cohort of swimmers that came of age after Hedy and Fritzi, three particularly exceptional Hakoah girls — Judith Deutsch, Ruth Langer and Luci Goldner — were chosen to represent Austria at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games. Talented Ruth, 15, the youngest of the three Olympic hopefuls, initially took up swimming because it was an arena where her more academically successful brother did not venture, while Luci, the backstroke champion, eclipsed her athletic brother.

But the drumbeat of Nazism had begun to sound, and Judith especially — the star who set 12 national records in one year and received Austria’s highest athletic award — had to make an intensely personal decision that weighed ambition and drive against moral courage. Within the context of a heated international debate about whether attending the Olympics was tantamount to supporting Hitler’s Germany, the three champions announced in the press their painful and prescient decision to boycott the Berlin Games. This was not an obvious choice at the time. Few athletes, Jewish or not, joined the boycott. Austrian officials swiftly retaliated by issuing a ban that forbade the three women from competing ever again and stripped them of their titles. In 1995, when the Austrian government apologized and reinstated the champions’ records, Judith, Ruth and Luci — who had settled respectively in Israel, England and Australia — refused invitations to go to Vienna for the ceremony.

When in March 1938, Germany took Austria in the Anschluss, the Gestapo ransacked the Hakoah offices and closed swimming pools to Jews. Perhaps Hakoah’s greatest institutional victory was its commitment to getting thousands of its members safely out. Dr. Rosenfeld, who fled to London, organized tirelessly to match over 100 swimmers, and often their families, to countries with opportunities for refugees.

Some of these girls’ families had never been keen on their daughters’ unladylike preoccupation with competitive swimming, and some upper-class families had disapproved of Hakoah’s ideological leveling of social class. In the end, though, these feisty, progressive girls were responsible not only for breaking barriers as females and as Jews, but they also became, in many cases, the young agents of their families’ survival.

Karen Propp is the author of two memoirs and co-editor of Why I’m Still Married: Women Write Their Hearts Ouot n Love, Loss, Sex, and Who Does the Dishes. She is writing a young adult novel based on the lives of the Hakoah girls.