Living Inside a Russian Doll

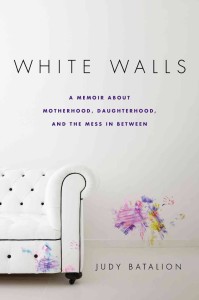

White Walls: A Memoir About Motherhood, Daughterhood, and the Mess in Between by Judy Batalion (NAL, $16) is reminiscent of those nested Russian dolls. First there is Bubbie, Batalion’s maternal grandmother, a Polish Holocaust survivor who swam the Vistula with her sisters. Nested inside is her mother, a hoarder who raised Judy and her younger brother Eli in a Zionist-socialist home lined with tuna cans, magazines, and cereal boxes and who refused to leave home for years on end. Then there is Batalion herself, our narrator, who escapes the clutter of her upbringing first to Harvard and then to London, where she completes a Ph.D. in theories of domestic representation and ultimately marries a fellow child-of-a-hoarder. And finally we meet Batalion’s daughter Zelda (named for Bubbie), an opinionated and strong-willed toddler with her own sense of how to decorate and fill her space. The memoir traces Judy’s pregnancy with Zelda while interweaving flashbacks to her Montreal childhood and her coming-of-age, providing context for her anxieties and ambivalence about becoming a mother: “Would my baby be a rebirth of my mother: needy and unhinged? Is parenting a child the same as parenting a parent?”

White Walls: A Memoir About Motherhood, Daughterhood, and the Mess in Between by Judy Batalion (NAL, $16) is reminiscent of those nested Russian dolls. First there is Bubbie, Batalion’s maternal grandmother, a Polish Holocaust survivor who swam the Vistula with her sisters. Nested inside is her mother, a hoarder who raised Judy and her younger brother Eli in a Zionist-socialist home lined with tuna cans, magazines, and cereal boxes and who refused to leave home for years on end. Then there is Batalion herself, our narrator, who escapes the clutter of her upbringing first to Harvard and then to London, where she completes a Ph.D. in theories of domestic representation and ultimately marries a fellow child-of-a-hoarder. And finally we meet Batalion’s daughter Zelda (named for Bubbie), an opinionated and strong-willed toddler with her own sense of how to decorate and fill her space. The memoir traces Judy’s pregnancy with Zelda while interweaving flashbacks to her Montreal childhood and her coming-of-age, providing context for her anxieties and ambivalence about becoming a mother: “Would my baby be a rebirth of my mother: needy and unhinged? Is parenting a child the same as parenting a parent?”

This is not a light book — the author chronicles her efforts to convince her father of the reality of her mother’s illness and commit her mother to a psychiatric word — but it is leavened by Batalion’s energy and humor: She refers to her baby’s internal kicking as “domestic abuse,” marvels at a special room for Jewish neuroses in a high-end NYC baby store where pre-purchased items are stored until after the baby is born — for superstitious parents; and describes a “Babies and Pets” workshop for expecting couples, where she and her husband are surprised to discover that they are the only couple more concerned about how their pet will adjust to the baby than vice versa. While living in England, she tried to make it as a stand-up comic, and even wrote her own one-woman show in which she played both her grandmother and her imagined daughter. “Judaleh,” she continues to hear her grandmother speaking to her long after her death; even though the voice she hears more often is that of her mother, whose suicidal phone calls send her running back home time and time again.

Batalion’s story is most engaging and compelling once she finds herself — when she meets and marries her husband, navigates matters of Jewish identity and shared space with him, and when they raise their daughter together. The book would have been tighter with one or two fewer ex-boyfriends thrown into the mix; but then again, isn’t it true of life itself that some clutter is inevitable? Ultimately, this is the lesson that Batalion learns as well: No matter how much she tidies, she cannot control the disorder of motherhood. And that if she is so focused on removing the clutter, she will not have time to look at her daughter: “In my desperate attempt to not-be my mother, I ended up only repeating her behavior. She’d tried to make up for her childhood by filling her home with objects; I tried to make up for my childhood by ridding them. Both of us could be blind when it came to our children.”

Ilana Kurshan works in book publishing in Jerusalem.