Esther Singer Kreitman In the Spotlight

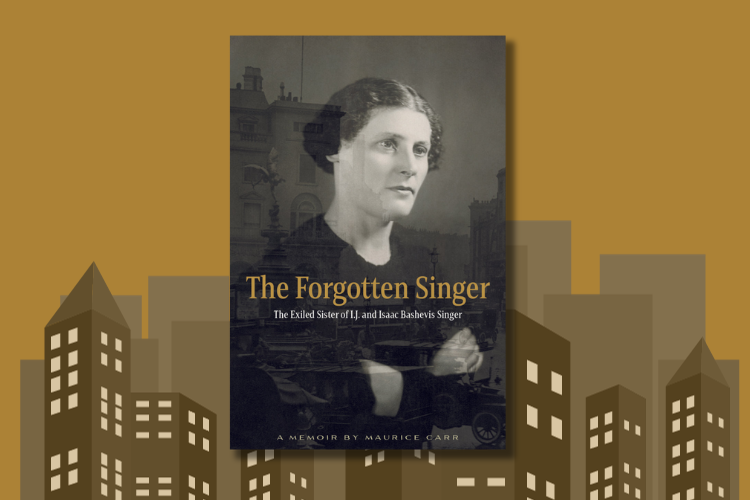

Esther Singer Kreitman (1891–1954) was called many things in her lifetime: unattractive, household drudge, hysteric, epileptic, madwoman, controlling mother, a woman possessed by a dybbuk. These were the words—or epithets—her family used. Less often used were the words that should have been associated with her: novelist, short story writer, translator. In The Forgotten Singer: The Exiled Sister of I.J. and Isaac Bashevis Singer (White Goat Press), the newly published memoir by her late son Maurice Carr (aka Morris Kreitman), “unloved and unloving” is a refrain that often describes her relationship with the members of her family.

As one might expect from a memoir, the series of vignettes Carr offers tells of his work, his relationship to his parents, his romantic and sexual awakening, his impressions of his family. The title of Carr’s memoir points to the fate Kreitman shared with many women who wrote Yiddish prose. It “forgets” her name, but names her brothers. Women who wrote in Yiddish have not, in fact, been “forgotten,” as the many new translations of women’s writing attest. Nor, for the most part, were they exiles, but instead emigres or immigrants. And women who did write Yiddish are all too often referred to as a (more famous man’s) sister, daughter, or wife. Kreitman is almost always associated with—or subservient to—her brothers. This memoir, published posthumously with his daughter’s introduction, adds another dimension to such associations.

In their own memoirs and semi-autobiographical works, Carr’s mother and uncles described their parents (Carr’s grandparents) as learned and terribly mismatched: the father, a Hasidic enthusiast, hopelessly impractical but loving; the mother, a Misnagdic rationalist, unemotional, dour. Carr describes his own parents as equally mismatched: his father aloof and largely absent; his mother clinging so tightly to her son as to make him feel guilty for falling in love with another woman. As soon as his parents began their unhappy married life in Antwerp, his mother took off her wig and his father shaved his beard. Rather enigmatically, Carr describes himself as growing into “a Torah-loving agnostic,” and also growing into what may be considered the family business: writing.

In her foreword to The Forgotten Singer, Carr’s daughter, Hazel Carr, describes her grandmother’s London home as “dark, damp, cold, and dreary” and sees her as both “dumpy” and frightening. But, to her, Esther Kreitman was simply “Buba.” Not included in this book, but intriguing in its own right, is a painting by Hazel Carr in which I.B. Singer is on the left, I.J. Singer on the right, and Esther Kreitman between them. (A decade ago, when I gave a series of lectures at the Yiddish Book Center entitled “The Family Singer,” Bashevis’s son and three of his son’s children attended. Hazel Carr, who intended to come but had to cancel her trip, sent that painting.) It may be the only depiction of the three siblings as a unit. The siblings, blue eyes staring straight ahead, are together in the frame as they were not in their lives.

The brothers never paid much attention either to their sister’s life or to her writing. Isaac Bashevis Singer’s appraisal— “I do not know of a single woman in Yiddish literature who wrote better than she did”—is both grudging and dismissive of women who wrote in Yiddish. Or perhaps it is simply a sign of his ignorance of women’s writing: “I do not know…”.

In the last decade of her life, Kreitman was an active participant in the London literary magazine Loshn un Lebn (Language and Life), and also in socialist politics. The two books she translated into Yiddish may well have contributed to the pervasive myth of her contrariness, since they were hardly likely to meet with a warm reception from her intended audience. In 1929 she translated Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, following it in 1930 with George Bernard Shaw’s Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism. Her most well-known novel, Der sheydim tants (The Demons’ Dance, 1936) was followed by the novel Brilyantn (Diamonds, 1944) and a collection of short stories, Yikhes (Lineage, 1950). They have all been translated into English and so have fared better than most Yiddish prose by women. Her son translated the first novel, which appeared as Deborah (1946) after its main character, and was later restored to the author’s own title, The Dance of the Demons. Diamonds (2009) was translated by Heather Valencia, and the short story collection appeared in English as Blitz and Other Stories (2004), translated by Dorothee van Tendeloo with a dedication to the memory of Maurice Carr.

Kreitman shares the fate of many women whose works were often read as memoiristic, thus diminishing the imaginative work…

Translation, like novels and stories, ran in the family too. Carr translated an I.J. Singer novel (Shtol un Ayzn/Steel and Iron) later re-translated by the author’s son, Joseph Singer. (In Carr’s translation, the title was changed to Blood Harvest.) Bashevis Singer translated Thomas Mann and others. In the anthology Jewish Short Stories of Today (1938), Carr—under the name Maurice Kreitman—included eight of his own translations from Yiddish, two by his uncles, one by his mother. As Martin Lea, the name appearing on the novel he published, Carr also included a story of his own. He notes that this “flagrant family affair” was masked by the varied names under which the stories appeared: Esther Kreitman, Israel Joshua Singer, Yitzhak Bashevis, Martin Lea. Who would know they were related? Name changes seem like a kind of shape-shifting for this family, distancing themselves from one another. Esther was known as Hinde in the family, and she dropped Singer when she published her works. Israel Joshua Singer sometimes wrote under the name G. Kuper, the maiden name of his wife (Genya Kuper). Isaac Singer wrote under several pseudonyms, most famously as Bashevis, derived from Batsheva, his mother’s name. Moyshe Kreitman/Morris Kreitman/Maurice Carr/Martin Lea were all the same person. Such shifts in names is another kind of translation. Derived from the Latin word for carrying something across, translation allowed not only for bringing Yiddish literature to English readers, but also bringing each of these writers into new domains.

Esther Kreitman’s most well-known story is “The New World,” (as translated in the short story collection Blitz, and in Lilith magazine in Barbara Harshav’s translation). We meet the story’s first-person narrator when she is in utero. (English readers may be reminded of Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, a novel Kreitman probably knew.) Kittens are born in the same bed as the baby and both are equally unwelcome. off to a wetnurse, the baby is put under a table where she lives for the next three years until she is brought home nearly blinded by dust and cobwebs. Carr repeats these details as biographical facts about his mother. He writes that Kreitman heard the story of the table and her eyesight from her own mother. There is, of course, no way to verify the details of Kreitman’s memory or her mother’s, but it is curious that Carr repeats it without mentioning his mother’s short story. In this regard, too, Kreitman shares the fate of many women whose works were often read as autobiographical or memoiristic, thus diminishing the imaginative work of prose literature. Some of her work is certainly semi-autobiographical, but a tale told from the perspective of a fetus and an infant reminds us, too, of the creative force of her stories and novels.

White Goat Press, an imprint of the Yiddish Book Center, has been instrumental in bringing Yiddish literature by women (and men) to an English-reading audience. Although written in English, Carr’s memoir contributes to this growing interest in women’s Yiddish literature. Esther Singer Kreitman is not the main protagonist of this book—it is, after all, a memoir about and by Maurice Carr—but the book does underscore that, whatever misfortunes may have befallen her, she has certainly not been forgotten.

Anita Norich is Professor Emerita, University of Michigan and a translator and scholar of Yiddish literature.