An Angle on Mikvah

Trying to inspire secular readers

Traditional Judaism regards a menstruating woman as ritually impure and therefore sexually impermissible to her husband. By immersing in the purifying waters of the mikveh (ritual bath) seven days after her menstrual flow ceases, she returns to a state of ritual purity.

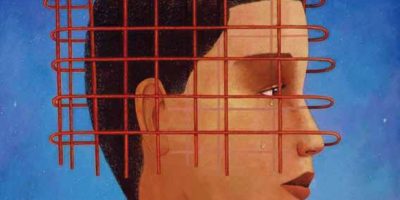

Classic rabbinic thought views menstruation, niddah, as representing the fallen state of human beings from the time of the expulsion from the Garden of Eden; niddah also connotes women’s flawed reproductive state, as each menstruation is viewed as the death of a potential life. Against these traditional disparaging rabbinic views of women’s monthly cycles, Varda Polak-Sahm, in The House of Secrets: The Hidden World of the Mikveh, (Beacon Press, $28.95) seeks to understand why and how some contemporary Israeli women choose to follow these ancient laws, which are known rather archaically as taharat ha-mishpacha, “family purity.”

From awe to antipathy, the ritual monthly immersion in the mikveh elicits widely divergent reactions in 21st-century women. Polak-Sahm, a secular Israeli with Sephardic, ultra-Orthodox, Me’ah Shearim roots, posits the framing questions of her book: Why do some Jewish women choose to immerse themselves in the mikveh? Do they do it for spiritual reasons, or possibly as a fertility strategy? Do they act out of superstition, to ward off possible birth defects, or as a ploy to maintain sexual excitement in a marriage? Or is it because a woman is commanded to do so as part of the laws of family purity?

A folklorist, author, photographer and seventh-generation Jerusalemite, Polak- Sahm turns her keen and compassionate attention to explore what motivates contemporary Israeli women to come every month to the mikveh. She relates her own traumatic first-time experience of mikveh preceding her first marriage. Years later, she returns to the same mikveh, just before her second wedding. She experiences a personal transformation from painful alienation to a profound sense of sacredness and sisterhood. She recalls, years later, “Out of the five senses a sixth was born: I was flooded with an elemental emotion so stunning in its intensity, so acute, it was as if every fiber of my being was stirring wondrously to life.”

Eleven years later, that radical transformative experience prompts her to return to the same mikveh yet again, as she seeks to understand herself and to explore the motivations and experiences of other Israeli women. Her book is unique amongst works about mikveh in that she draws on the deeply personal and revealing narratives of religious and secular women who come regularly to immerse.

The stories of these women come alive here as Polak-Sahm writes of religious women for whom immersion is a commandment; of secular women for whom immersion constitutes spiritual renewal; and of the balaniyot, or mikveh attendants, who consider their occupation a calling from God. As such, this book aims to offer inspiration for Jewish women of all backgrounds.

Marion Lev-Cohen is in her last year of rabbinical school at HUC-JIR, New York. Her current project is creating a liberal mikveh for the New York area.