Women Who Are Rabbis Experience Their Own Brand of Harassment

“I’ve been harassed. It’s happened to every female rabbi I know,” Rabbi Rebecca Sirbu said. “People have an overwhelming sense of discomfort with women rabbis, because they’re women.”And female rabbis face an additional burden of harassment because they are occupying a powerful position once permitted only to men. “People have to start seeing women as religious leaders and thinking about what that means,” Sirbu, director of Rabbi’s Without Borders, told me.

Even rabbinical students don’t escape sexist workplace offenses. One, we’ll call her H., emailed family and friends to describe, wearily, three incidents she’d experienced within a single 72-hour period. There was the man who told her that the service she’d just facilitated had a “distinctly feminine energy.” The man who announced to his buddy that she was “cuter” than the other (male) rabbi. And the man who told her that she made horizontal stripes “work,” which his wife, apparently, could not do.

“I am used to restraining myself,” she wrote in her email, “because everybody knows that nobody likes an angry woman, because my congregants like that I am often smiling, because an abrasive interaction will rebound negatively to me.”The experience of sexual harassment is one that women everywhere share—in all workplaces, learning environments, and religions. But a particular paradox plays out in the work lives of women rabbis, who are supposed to be powerful leaders yet are at the same time often viewed as amusing stand-ins for the real thing: a man in the pulpit. Where male rabbis command immediate respect from those they serve, too often women in these roles are made to feel unworthy—for no other reason than their being female. How, then, do we disrupt what seems like—but need not be—an inevitability for women on the bima?

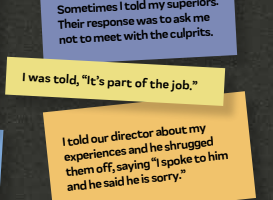

Over the past few weeks I’ve spoken with dozens of women serving as clergy; some are rabbinical students, others have been working as rabbis for decades. They all emphasized their reverence for the rabbinate, their feelings of privilege at being able to be part of this calling. Then they told me about being called a “sexy rabbi” when they wore heels when leading services, about being touched on the legs, and being asked out by congregants. They revealed their frustration when men calling themselves feminists acted surprised when they heard about women’s experiences, men who were then rewarded by positive attention when they later confessed their own inaction in the face of such misogyny.

Some of my respondents talked to other women—classmates or fellow rabbis—about these incidents. Others, for fear of angering congregants and losing their jobs, didn’t. For reasons that resembled (if not duplicated) those articulated by H., restraint characterized their responses to the men insulting them.

If you search the course catalogs of U.S. rabbinical schools (Conservative, Reform and Reconstructionist) for “sexual harassment,” you won’t find anything. A more productive tactic is to search for the word “boundaries,” and then you’ll turn up a number of seminars and other teachings on how to establish ground rules, including sexual boundaries, with congregants. These are the kind of seminars soon-to-be-rabbis take to learn how to manage expectations, conserve their energy, and adapt to their new role as clergy. “We talked about how to protect our sanity, how to maintain private space,” a 2007 Reconstructionist Rabbinical College graduate told me. “But one of the main messages was also ‘Don’t sleep with your congregants’.”

Although it has been more than 45 years since Rabbi Sally Priesand became the first woman rabbi ordained in North America, there’s not yet an obvious cure for the misogyny that still greets her successors. What’s happening to women rabbis will not be solved with a mandatory seminar on why it’s unethical to date congregants. It’s more complicated than that, and far more treacherous. What’s needed is to uproot the culture that allows for sexism to persist. We—and it is a “we” and not a “they”—have let misogyny become so ingrained that it has become difficult to filter out sexism from what we consider acceptable interactions between women and men. (And, as Elsie Stern, vice president for academic affairs at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, pointed out, “This conversation has been framed in deeply heteronormative terms.”)

“I feel lucky that I haven’t experienced sexual harassment,” some female rabbinical students told me when describing their encounters. They all, however, know women who have been harassed, and they themselves describe consistent experiences with “microaggressions”—verbal and nonverbal messages that marginalize people. These subtler insults often leave women stunned and uncomfortable, feeling like something has just happened, yet we’re not necessarily able to articulate what. We might even feel we’re being paranoid.

What are some of these less obvious assaults? Zoe McCoon is a second-year rabbinical student at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. Last year, before the advent of the MeToo hashtag, she was part of a group of HUC students and faculty who convened a campus gathering to talk about sexual harassment. The entire campus was encouraged to come, including, McCoon emphasized, administrators and non-rabbinic academics. The event included examples of microaggressions, and participants were asked to respond to what they saw in the dramatizations based on real events. “People directing all their questions or comments to the male rabbi, when the female rabbis is standing right there. Or a man saying the same thing as a woman in class, but it’s the man’s opinion that catches the traction… People want to think they’re not being harmful,” said McCoon, “but are they listening?”

Perhaps it’s time to revisit the part in a rabbi’s job description that says she has to preserve relationships with congregants at all costs.

“My congregants don’t necessarily perceive their behaviors or comments as insulting,” a congregational rabbi who asked to be anonymous told me. “It would be nice if they did, because that might stop them from making comments about being surprised that I’m willing to do hagbah (lifting of the Torah), for example. A rabbi’s job is to change the culture, though, and also to maintain relationships, so I’m always thinking about how to keep relationships while changing someone’s mind.”

“When people realize they can get away with those,” Kohenet Sarah Chandler, Hebrew Priestess and Jewish Educator said about such comments, “they feel more comfortable with more directly aggressive behavior.”

Often, I was told, the men making misogynistic comments and physical advances were from “a certain generation, a certain time,” when such behavior was deemed acceptable. Some respondents believe it’s hard to convince men that times have indeed changed. But since the women’s movement is about to turn 50, ignorance seems a weak excuse for misogyny. Similarly, there’s the stereotype of the awkward Jewish man who just doesn’t know how to act around women, and so we let his offenses go. His inappropriate and discomfiting actions—lingering, standing too close—are deemed acceptable because he’s probably a mensch, maybe even a Torah scholar.

The responsibility for changing minds, and learning to adapt your own behavior to a potentially (or already) toxic situation, is prevalent among all women, and this includes women rabbis and rabbinical students. “Creating healthy boundaries and enforcing them, that’s on me,” said a third-year rabbinical student, who described the gender dynamics in her class as “problematic. There are always comments from male students who just do not get it.”“Rabbis have a lot of power.” This was one of the assertions I heard again and again. Yes, of course. But should the person who’s experiencing the harassment—the one who might doubt herself because she can’t put her finger on exactly why she’s uncomfortable and who’s trying to do a good job despite these circumstances—be the one to take men aside to explain to them why they can’t make comments about her skirt length?

Perhaps it’s time to revisit the part in a rabbi’s job description that says she has to preserve relationships with congregants at all costs.

Rabbis have power, but sexual harassment is specifically about taking that power away from the person being harassed. Creating healthy boundaries isn’t just about not dating your congregants or not sharing your cell phone number, it’s also about not doing certain kinds of exhausting emotional labor, like explaining to someone why dehumanizing you is not acceptable. If men want to be part of effecting change, they might be the ones to take that congregant aside and help him understand and change his behavior.

Undoing cultural norms is complicated. Rabbi Joanna Samuels, speaking at “Revealing #MeToo as #WeToo in Jewish Communal Life,” an event sponsored by the Jewish Women’s Foundation of New York this past January in New York City, reminded the attendees that the Jewish community—even progressive organizations within it—are still creating all-male panels of “experts,” managing not to see women (and queer folks, and people of color) as thought leaders. If we’re interested in changing what women rabbis experience, then we must truly invest, and demand that others invest, in undoing this reality.

“Your policy is less important than your culture, which sends implicit messages about your priorities,” Human Resources Consultant Fran Sepler told an audience of more than 100 rabbis who joined a recent webinar on “#MeToo from the Pulpit: A Rabbi’s Role in Creating Safe, Respectful Synagogue Communities.” It’s time that we begin consciously tearing down the misogynist culture that has been left untouched for far too long—and build a new, feminist culture instead.

“I am a powerful and sacred vessel unwilling to perpetuate your comfort-able narratives of ‘how the world works’ that are breaking wide open,” emailed the rabbinical student H. “I will not stand by as you try to plug your ears and hush the discomfiting sound that is the roaring tide rolling in.”

Chanel Dubofsky is a journalist and fiction writer living in Brooklyn.